I spent months reading this book, which is unusual for me. I tend to read a book straight through once I’ve started, but with this book (and maybe given the time I was reading it) I felt I needed to go slow and take breaks. There are parts of this book I flew through, and others that required more concentration. But taken as a whole, this book was powerful and it gave me such a new understanding of World War I and how the time period changed people.

I spent months reading this book, which is unusual for me. I tend to read a book straight through once I’ve started, but with this book (and maybe given the time I was reading it) I felt I needed to go slow and take breaks. There are parts of this book I flew through, and others that required more concentration. But taken as a whole, this book was powerful and it gave me such a new understanding of World War I and how the time period changed people.

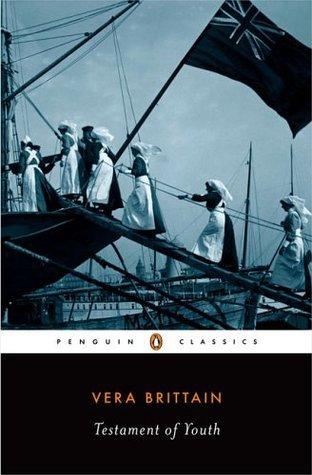

Testament of Youth is Brittain’s autobiography. She begins as a young woman trying to get into Oxford at a time when no one expects a woman of the upper class to go to college. Brittain is an academic at heart, loving poetry, writing, and debate. She is clearly intelligent and ambitious, and willing to fight to make more of herself.

As she writes of Oxford, and the beginnings of her first relationship, war is on the horizon. Brittain writes with a very slow, detailed pace, so where I might have imagined that war just struck all at once, the reality is very different, and of course the conflict builds over time and the country, and its citizens, have to decide what to do. Initially, Brittain is affected by the war mainly because of how it affects the men around her.

As her brother and his friends give up college to enter the war, she can no longer see herself going to classes and writing papers. She leaves school to enter the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), an organization of volunteers that worked with military hospitals during World War I and II. She stays close to home, as the VAD didn’t send most women overseas at first. Nursing is a new thing for Brittain, but despite the challenges, she is happy to work hard and to contribute to the war effort, particularly to ease her worry about the men she loves.

For me, this book really picked up when Brittain leaves England and serves in Malta and France. It was fascinating to see these places through her eyes, knowing they were real experiences. Brittain writes a lot about how sheltered young women were before 1914. Now she’s traveling on ships, seeing foreign countries, and learning about medical care. She encounters hardships, including the very real danger of ship travel at that time, but these make her stronger. Since much of this book is based on her diaries from the time, the reader can see her grow and develop. At the same time, she brings the perspective of a woman in her thirties, with a greater understanding of the world.

People’s lives were entirely their own, perhaps – and more justifiably – when the world seemed enormous, and all its comings and goings were slow and deliberate. But this is so no longer, and never will be again, since man’s inventions have eliminated so much of distance and time; for better, for worse, we are now each of us part of the surge and swell of great economic and political movements, and whatever we do, as individuals or nations, deeply affects everyone else. We were bound up together like this before we realized it; if only the comfortable prosperity of the Victorian age hadn’t lulled us into a false conviction of individual security and made us believe that what was going on outside our homes didn’t matter to us, the Great War might never have happened.

One thing I found so interesting, and so troubling, about this book is that it’s published in 1933, just before the outbreak of World War II, which really brings home the fact that the people who lived through World War I had to see it all happen again just 20 years later. It was striking to see this through the eyes of someone who doesn’t know World War II is coming (but who clearly sees signs of it).

There is so much in this book, I can’t address most of it in a simple review. As a former literature major, I loved the way Brittain integrated poetry throughout this book. I found myself wondering, is this how people wrote diaries and letters in that time? Were they so much more educated, and their writing so much more eloquent than ours is today, or are Brittain and her friends exceptional? I’ve seen it said that this is not just a book about war, it’s also a book about writing and literature, and I definitely see that.

It’s also a book that clearly sets World War I in the context of what comes before and after, at least in England, and particularly for women and their identity. Brittain writes about women in the thirties being so much more modern than women in the 1910’s, and at first I sort of laughed at that (the 1930’s seeming like a VERY long time ago). But in this book you really see how World War I changed the perceptions of women, just as it changed our ideas about class and society.

Not all our experience could change us from the earnest, idealistic War generation into our flippant juniors the post-war youth, who had never been taught to think the terms of sex indecent and to see its facts, if at all, through a glass darkly.

I had heard that the post-war part of the book is a bit slow, and I can understand that, but I found it much more interesting than the early part of the book. At first Brittain struggles to return to regular life after the war, but she goes back to school, then builds a career, and fights for legislation on women’s rights. Women in England got the vote during the war (although it was only older women) but that’s only the beginning. Brittain fights for marriage reforms, such as women having similar custody rights as men, and more protections for women against domestic abuse (e.g. abuse should be as much of a justification for divorce as infidelity). At the same time she is confronted with what marriage and childrearing might mean for her (England at that time wants women to reproduce but also recognizes that there are very few young men left to reproduce with).

For a woman as for a man, marriage might enormously help or devastatingly hinder the growth of her power to contribute something impersonally valuable to the community in which she lived, but it was not that power, and could not be regarded as an end in itself. Nor, even, were children ends in themselves; it was useless to go on producing human beings merely in order that they, in their sequence, might produce others, and never turn from this business of continuous procreation to the accomplishment of some definite and lasting piece of work.

This seemed as relevant today as it did then.

The reorganization of society in such a fashion that its best women could be both mothers and professional workers seemed to be one of the most acute problems which my generation – and to a lesser but still important extent all subsequent generations – had now to face.

I was so impressed with Brittain’s strength and dedication to her causes, and her willingness to challenge what women can do. She’s writing about herself but it never feels like she sees herself as extraordinary.

I will always remember reading this book at the same time as I voted for my first female president, and then watched her lose that election to an abuser and misogynist. We haven’t come very far, after all.