As is my tendency, I like to wade carefully into other disciplines from time to time to examine what components they can bring to the conservation table. I do not profess any sort of expertise when I do so, but if I require a true expert for research purposes, then I will collaborate with said experts.

I often say to my students that in many ways, the science of sustainability and conservation is more or less resolved — what we need now is ways to manage the human side of the problems we face. The disciplines that deal with human management, such as psychology, economics, political science, and sociology, are mainly pursuits of the humanities (have I just argued myself out of a job?).

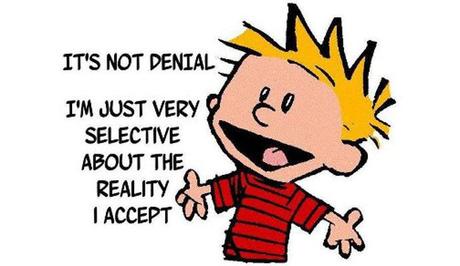

On the topic of human psychology, I think most people involved in some way with biodiversity conservation often contemplate why human societies are so self-destructive. Even in the face of logic and evidence, people deny what’s going on in front of their eyes (think anti-vaxxers, climate-change denialists, etc.), so it should be no wonder why many (most?) people deny their own existential threats. Yet, it still doesn’t seem to make much sense to us until we put the phenomenon into a psychological framework.

My apologies here to actual psychologists if I oversimplify or otherwise make mistakes, but the following explanation has done a lot for me personally in my own journey to understand this conundrum. It is also a good way to teach others about why there is so much reticence to fixing our environmental problems.

The idea is a rather simple one, but it requires a little journey to appreciate. Let’s pop back to the 1970s with the publication of Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1974 (ironically, two months after his own death). In this book, Becker examined the awareness of death on human behavior and the strategies that we have developed to mitigate our fear of it. This particular quote sums it up nicely:

This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, and excruciating inner yearning for life and self expression — and with all this yet to die

Ernest Becker in The Denial of Death (1973)

The upshot is that we have evolved a whole raft of coping mechanisms to this personal existential dread. Some engage in overly hedonic pursuits to numb the anxiety; others try to “tranquillise themselves with the trivial”, essentially ignoring the terror, while others still manage the dread through religion and the hope of an existence beyond the mortal.

Interesting read, but the book’s real value in my opinion was the foundation for what has become known as terror management theory proposed by Greenberg, Solomon, and Pyszczynski and popularised in their book The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. Therein they expand on this notion of escapism from the terror of biological reality (death), providing an empirical psychological-evolutionary framework for the theory.

Terror management essentially posits the following (nicely summarised in a 2001 paper by the same trio:

- we as individuals are highly motivated to maintain confidence in the veracity of our cultural worldview;

- we develop faith that we are valuable people (i.e., we have self esteem);

- such that when either our worldview or self esteem is threatened, we respond defensively to bolster our faith in our culture and ourselves even further;

This is where we sort of depart from the self and contemplate the grander application to societal threats. The logical extension of terror management theory of the individual is to extrapolate its tenets to the human predicament. If threats to individual constructs of self esteem and cultural worldview elicit strong defensive responses when challenged, how much do existential threats to all amplify the defensive behaviour?

In other words, when faced with prospect of an impoverished Earth where the existence of the natural life-support system upon which human society utterly depends is threatened, then one can logically predict that many, if not most, of society would respond even more aggressively to any challenges that we are doing the wrong things collectively.

I don’t know about you, but this explains a lot to me, from right-wing denialism, to concerted efforts to counter sustainable practices of any form (the ‘exploit everything’ attitude).

Finally, let’s look at this from the perspective of a parent. In 2019, the former journalist Catherine Ingham published a long-form essay called Facing Extinction, where she poignantly captures this existential dread in the evolved defences of a parent:

It is built into the DNA that parents (not all, of course) love their children above themselves. They would sacrifice anything for them. So to think that there will be no protection for their children in the future, that no amount of money or homesteading or living on a boat or in a gated community or in a bunker or on a mountaintop with a secret garden will save them is too unbearable a thought to hold for even a second. I have also noticed a flash of anger arise in the midst of the distracted look on their faces, an almost subliminal message that says, “Don’t say another word on this subject.”

Catherine Ingham in Facing Extinction (2019)

As a parent, I can relate, but I also have the benefit of all that evidence and knowledge about the nature of that existential threat. While the development of this terror management theory applied to the entire planet might help to explain a lot of our frustration, how can it help us move forward?

I suppose one of most pertinent applications of the theory is to provide us with a deeper understanding of what motivates people to do environmentally (and therefore, personally) counter-productive activities. If we can reach into the core of that motivation, maybe we have a chance of shifting behaviours to more proactive outcomes?