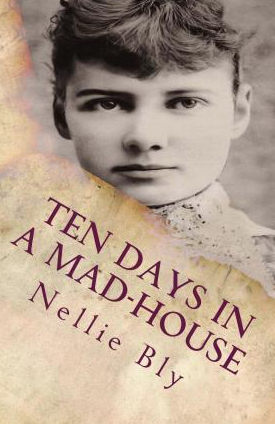

In 1887, young journalist Nellie Bly accepted an undercover assignment and had herself committed to the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island, New York. In Ten Days in a Mad-House she tells her story. The account was first published as a series in a newspaper and then, at the end of 1887, as a book. Nellie Bly was only nineteen when she accepted the assignment.

There were rumours of neglect and violence at Blackwell’s Island and her editor wanted her to look into this. Nellie accepted but didn’t think she’d stand a chance to be committed because, after all, she had absolutely no mental health problems. First, she went to a boarding house for poor women where she acted as if she was crazy. She only spent a night there and was then questioned by the police and a judge and sent to a psychiatric institution. She was more than surprised that she was able to fool ordinary women, police, and judges. But surely doctors would see through her ruse. She was afraid that once they would question her, she wouldn’t be sent to her real destination, Blackwell’s Island. She shouldn’t have worried. It soon became obvious that the doctors didn’t really care. She was poor, seemed to have no family, and acted in a strange way – enough to be sent to Blackwell’s Island from where she most likely would never return.

Together with a few other women, who were just as sane as she was, Nellie was finally sent to Blackwell’s Island. What followed was a real horror trip.

Blackwell’s Island was by no means an exception. Everywhere in the world there were such asylums for poor women (and men too), many of which were initially not ill at all but were committed because their families wanted to get rid off them or because they didn’t behave as they should have. There were cases of illness too, for sure. Many of the cases Nellie Bly describes have been brought to the Island because of language problems. There are many Germans in the asylum who don’t speak any English. When they react with fear or anger, it is seen as a symptom of their illness.

A pretty young Hebrew woman spoke so little English I could not get her story except as told by the nurses. They said her name is Sarah Fishbaum, and that her husband put her in the asylum because she had a fondness for other men than himself.

The account is absolutely shocking. The way these women are treated would have tested the healthiest and strongest, but for women with any kind of mental health or other health problem, the treatment was atrocious. It reinforced their illness or, in many cases, pushed them over the edge.

But here was a woman taken without her own consent from the free world to an asylum and there given no chance to prove her sanity. Confined most probably for life behind asylum bars, without even being told in her language the why and wherefore. Compare this with a criminal, who is given every chance to prove his innocence. Who would not rather be a murderer and take the chance for life than be declared insane, without hope of escape?

There are many awful things in the asylum. Some of the worst are: the cold, the food, the brutality, the neglect.

It’s constantly cold at the asylum, but the women don’t even get proper clothing. When they complain, they are either hit or brought to other, more awful wards. The food sounded so disgusting that reading about it made me gag. It’s not even food. It’s horrible slosh. Many of the women can’t eat it; it makes them vomit. For that, too, the nurses chastize them. Personal hygiene is almost impossible. The descriptions of the way they are bathed and combed made me shudder.

My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold. Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head—ice-cold water, too—into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth.

And there’s the violence. Nurses deliberately push women to react and then punish them, by jumping or choking them. Or sending them to what they call chain gangs.

The longer, Nellie is there, there more she’s shocked and even scared. What if they can’t get her out?

During her stay, she’s seen by a few doctors, but they don’t listen to her. For them, her insanity is a given. They never question it. And since these women are poor, the treatment too, isn’t questioned. After all, they say, they should be grateful as they live off charity.

The days go by awfully slowly as there’s no distraction. They aren’t even allowed to read. This kind of treatment, as Nellie can observe, makes many a sane woman lose her mind.

What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 A. M. until 8 P. M. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck.

Nellie is freed after ten days and subsequently writes her account. It raised awareness and made things a bit better, as more money was collected to improve some of the conditions.

Ten Days in Mad-House is interesting for many reasons. It’s a first-hand account of a mental institution and therefore an important historical document. But it’s also interesting as a piece of early investigative journalism. The writing is very different from the way journalists write now. It’s far too detailed and quite dry.

If you’re interested in the history of mental institutions, the history of women and mental health, or the history of journalism, you’ll find this fascinating. But you’ll also find this fascinating if you’re interested in female pioneers. Nellie Bly was an amazing woman and went on to have an interesting journalistic career that ended when she married and took over her husband’s company.

Nellie’s story has been made into a movie in 2015. It looks quite good. I might try to track it down. I’ll just have to bear in mind that neither the women, nor the place, looked even remotely like those in the film.