When we set out for a humanist event in Syracuse, I didn’t imagine the road would take us to Somaliland.

Took 32 hours to get there; 42 getting home.

The capital, Hargeisa, is a dusty desert town (and I do mean dusty). In 1988, in the civil war, Hargeisa was bombed and 90% destroyed by Somalia’s dictator Siad Barre. It’s risen from the ashes, but the words “ramshackle” and “hardscrabble” come to mind. Most structures are single-storey and wretched, though there are some incongruous first-world-like pockets.

Thomas Friedman writes about “the world of order” versus one of disorder. Somaliland is mostly in the latter category, epitomized by a great trash blight. There’s no public sanitation nor any ethic against littering. We sat in on a student brainstorming session about the issue.

Typical dwelling

But Somaliland is not the heart of darkness; it’s poor, but thriving. Its people have positive attitudes. Women in particular are almost all well dressed (fully covered in this Muslim country). And there are lots of cars. Steering wheels on the right, yet they challengingly drive on the right. Many roads are paved, though often it’s hard to tell. No street signs; indeed, no street names. Terrible traffic. So, unsurprisingly, wrecked cars abound. No way to remove them. Another traffic hazard is zillions of goats wandering everywhere. I asked Jonathan how owners keep tabs on them. “Good question,” he replied.

Restaurant, with goats, we visited

There are myriads of tiny businesses, especially hole-in-the-wall restaurants, and — no surprise — numerous car parts sellers. Hargeisa is one giant bazaar. It was great to see so much enterprise. Government regulation being largely nonexistent, Somaliland might be a model of that bugaboo, “unfettered laissez faire capitalism.” Except that government’s absence also means scant rule-of-law protections, so any ambitious business is vulnerable to predation, greatly inhibiting economic development. An important point often lost in arguments over “unfettered capitalism.” Nevertheless, Somaliland’s enterprise culture begs comparison against countries like Cuba or Venezuela whose socialist fetish suppresses businesses. Result: impoverishment.

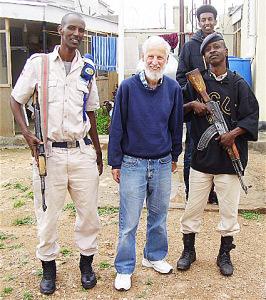

Me with our team

Was it safe? It’s actually a very peaceable place, with little crime or violence. Nevertheless, as apparently required by law, all our excursions were accompanied by two soldiers carrying AK-47s.

In one respect at least, Somaliland is actually more advanced than America. Most payments are made through a user-friendly system of instant smartphone transfers.

There is no tourism and white faces are novelties. I enjoyed waving to people, especially kids, out of our vehicle window, and getting waves and smiles back. Though once, walking in the street, a passing man said, “Fuck your mother.”

Yes, English is widely spoken. Education is highly valued here, and many little enterprises are schools. Though quality may be doubtful. I saw one sign for a “secendary” school offering English language instruction!

Partial view of Kaabe construction

Which brings me to Jonathan’s schools, with contrastingly high standards. Our first stop was the Kaabe School, which we helped finance, nearing completion as the prototype for an eventual national chain of primary schools. It’s an expansive complex, far better built than Somaliland’s norm, ultimately to educate around 700 students. Project leader Harry Lee does a fantastic job.

Saturday was “project day.” Wife Therese led an intensive poetry workshop. I delivered a powerpoint lecture on the Enlightenment (view it at www.fsrcoin.com/3.html). Trudy was great in stimulating discussion in the Q&A. A topic arose that’s central to daughter Elizabeth’s current work — using communication to change mindsets.

Elizabeth leading discussion

She had a relevant powerpoint on her laptop, so later gave an impromptu presentation and led a discussion. It was wonderful seeing her masterful performance.

Sunday we visited a sanctuary for cheetahs, rescued from poachers; then Hargeisa’s art and cultural center, modest but quite nice.

Photo by Harry Lee

On Monday we could now see Kaabe’s first classes, of kindergartners, in session. I didn’t really teach, but did help out, assisting one boy making English words with plastic letters, and some girls with block puzzles. The children seemed to have progressed amazingly in just a few months. This school is clearly a great thing, and to have helped bring it about was extremely gratifying.

On Tuesday I set out alone — well, with a driver and the obligatory soldiers — back to Hargeisa to get a microwave for the Abaarso teacher’s mess. I wasn’t sure this could be accomplished, but after a tortuous peregrination, including a change of car and escorts, I finally managed it, returning just in time for an important event:

Trudy. Jonathan, & DPW honcho

A visit to Abaarso by a top level delegation from Dubai Ports World, preparatory to announcing a swathe of scholarships and funding another school on the Kaabe model in Berbera.

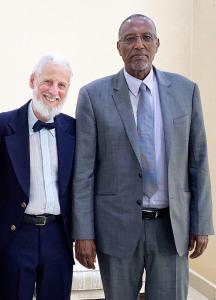

On Wednesday, Jonathan, Therese and I had a 45-minute private meeting in the Presidential Palace with Somaliland’s President Musa Bihi Abdi. Democratically elected in 2017, Bihi, 71, was a Somali air force pilot who became a top commander in the civil war against Siad Barre. A soft-spoken man, dignified without pomposity, a wise and decent human being (unlike certain presidents I could name).

With President Bihi (photo by J. Starr)

He spoke of the desirability of cooperation among different religious groups — a real issue for Jonathan’s project, still facing attacks on this score. And he was very strong about educating girls, understanding its importance for a country like his. During the meeting we were served delicious lemonades.

I’ve done a lot of foreign travel, but this was — like much else on this trip — a unique and thrilling experience.

Then we traveled an hour north on a “road” (hardly deserving the name) through a fairly desolate scrubland typical of the country. Passing many goats, camels, and giant termite mounds. With passengers squeezed in tight on this very bumpy ride, one of the soldiers volunteered to travel on the vehicle’s roof.

Barwaaqo

The destination was the other anchor in the schema, Barwaaqo University, a teachers college for girls, to eventually staff the Kaabe schools. Another impressive large campus; looked like a military base. A highlight was the debate club where Therese and I joined one of the teams. The question, chosen by the girls, was whether snacks in the school store should be free. Those girls were feisty debaters.

How many wives would (while suffering from an illness no less) enthusiastically join in an intrepid expedition like this? (Jonathan’s soon-to-be-ex-wife never did.) Therese and I have a true marriage in that word’s deepest sense. A blessing for which I’m boundlessly grateful.