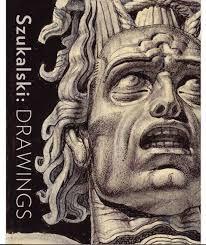

We stumbled upon this fantastical Netflix documentary: Struggle — The Life and Lost Art of Szukalski.

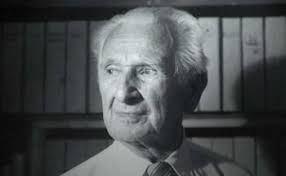

Then in 1971, in another California bookstore he recognized a Szukalski poster. Inquiring, he was told it was a gift from the artist, still living — in fact, quite nearby!

In obscurity. His monumental artistic career forgotten. Bray became the nexus of a new friendship circle around him, filmed many hours of Szukalski holding forth, and eventually published a book trying to revive interest in him. This documentary was produced by Leonardo DiCaprio.

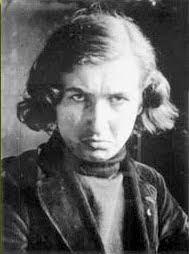

Yet a darkness seemed immanent in the film, and it duly materialized. In Poland Szukalski published a virulently anti-semitic periodical. The film-makers hadn’t known this when they’d started. Actually, Szukalski seemed to exude contempt not just for Jews but for all other artists, and indeed for all other humans apart from himself and his beloved wife Joan.

In 1939, Nazi aerial bombing obliterated much of Warsaw — including Szukalski’s studio, and with it, most of his lifetime artistic output. Two days later he literally crawled out from under the rubble. Eventually he and Joan arrived back in America; with nothing.

Meantime the holocaust of WWII seemed to sear out his anti-semitism, turning him into something of a universalist humanist.

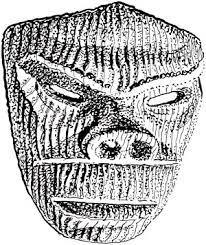

Meantime too, while his public artistic career did end, his private one did not. Szukalski spent four decades on his grand project, an effort to tie all of history together into one unified story, through art. He called it “Zermatism,” based on his idea that ground zero for the spread of human civilization was . . . Easter Island. (Actually one of the most isolated places on Earth.) He also believed we’re the product of primordial rapes by apelike yetis, accounting for all our ugly qualities.

This is pure crackpottery. Similar grand syntheses have long been a common enterprise for loopy autodidacts. That sad species was personified by Middlemarch’s Casaubon, who spent his life researching his projected masterwork, “a key to all mythologies.” When he died before completing it, his widow attempted to organize his notes and drafts, and found it all rubbish.

In Szukalski’s case, he produced homemade volumes filling a bookcase, with 25,000 pages and 14,000 meticulous and beautiful self-drawn illustrations. All identifying parallels among artistic images from disparate cultures. (Of course such parallels, even striking ones, are inevitable just from chance, if you compare many thousands of images.)