Sylvie Germain is an author I’ve meant to read for ages. I own half a dozen of her books, but it needed the nudge of my readalong to finally get to her. I’m certainly glad I chose Magnus because I don’t think I’ve ever read anything quite like this. It’s unique in its approach, structure, and complexity.

The prologue or “Ouverture” tells us that the book explores a man’s life. The life of a man with a faulty memory, a memory that has been fed wrong information and is full of gaps and holes. The narrator muses that no life is ever as chronological as we think it is and that all memory and stories are filled with holes and gaps. Because of this logic, the book isn’t divided into chapters but into numbered sections called “fragments”, which alternate with other sections called “Notes”, “Echoes”, “Sequences”. These sections add depth, give background information. They are accompanied by quotes from books and short biographies of real people like Dieter Bonhoeffer.

This might sound like it was a disjointed book but it wasn’t. It felt very organic and dynamic, like watching a puzzle take form. Most fragments were numbered chronologically, some earlier fragments however came later. This mirrored the protagonists way of remembering and let the reader take part in the experience of discovery.

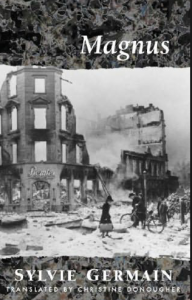

The beginning of the book is set in Germany, during WWII. A little boy called Franz-Georg comes out of a severe illness that has erased the memory of his earlier life. His mother fills the gaps with stories. He cannot make sense of most of what happens around him or of the roles his parents play. He only knows his father is a famous doctor and that when the war ends, they have to flee. Since not only his memory but his consciousness seem to have been wiped out, he knows nothing of the atrocities that took place in Germany and, unlike the reader, never suspects that his father was a doctor in a concentration camp.

Like so many Nazis, his father flees to South America where he dies in an accident. His mother, who doesn’t want to live anymore, sends her son to her brother who lives in London. The two siblings were on opposing political sides before and during the war. Lothar, Franz’s uncle, fought with the resistance with the famous pastor Dieter Bonhoeffer.

By the time Franz comes to London, he knows what happened in Germany and what role his parents played. How do you live with this kind of truth? Franz is almost crushed by it but there are other things that make him restless, give him a feeling of not belonging.

The book follows him to South America where he retraces his dad’s journey. Exposed to the sun and extreme emotions he has a breakdown and fragments from his early childhood emerge and he finds out the truth about his so-called illness. I didn’t see this twist coming and it hit me with full force. In this early fragment we are with the child during the bombing of Hamburg and witness a horrific tragedy. I don’t think I’ve ever come across any scene that captures the horror of being bombed so vividly. Nor have I literally felt the gaps of a narrative closing like this. Because a lot of what we read before tells us just as much as Franz knows, we’re stunned when his memory returns and the gaps are filled.

Magnus is the story of a life but it’s also a meditation on memory, loss, and guilt and how we handle them. Just like our own minds add bits and pieces, memories, information and anecdotes, the book adds elements from various sources. There’s a richness of details and information here that function like small doors that one can enter to find out more. You could read it without looking up anything, or you can follow the many leads Sylvie Germain has added. It’s very much Sylvie Germain’s book but enriched by the many quotes taken from other novels (Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo), nonfiction on war (Sebald On the Natural History of Destruction), plays (Shakespeare’s King Lear) and other sources.

The book also explores how postwar society dealt with Nazis. Many escaped and were never found, but some, like Eichmann, were brought to justice long after the war.

Dieter Bonhoeffer and his resistance group serve as a counterbalance to the stories of war criminals. I was familiar with his name but I didn’t know anything about his life. I will be reading more of and about him soon.

Sylvie Germain’s writing is at times almost scientific, then again it’s lyrical but it’s never warm. We’re always held at arm’s length, never get close to Franz.

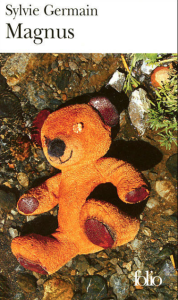

Later in the book, when Franz has remembered what happened before the so-called illness, he takes the name Magnus. Magnus is the name of his teddy bear, who has been with him all of his life. The use of this bear is another arresting element of the book. He too, undergoes changes, not only physically but his meaning changes too. He’s a sort of guide for Magnus because as long as he hasn’t solved the meaning of certain elements – the name that sounds nordic, a ear that has burn marks – Magnus, the man, still doesn’t own his story. It’s no surprise then, that Fragment 1, which comes in the middle of the book, reveals the bear’s secret.

I’m afraid, I could only scrape the surface of this beautiful and complex novel. I’d say it’s one of the best books on war and memory and the importance to remember our own story and the history of our society. For such a sophisticated novel, Magnus is surprisingly captivating and suspenseful. There are two powerful twists that I didn’t see coming. Truly a tour de force.

Other Review

*******

Magnus is the second book in the Literature and War Readalong 2017. The next book is the Czech WWII novel Closely Observed Trains by Bohumil Harbal. Discussion starts on Friday 31 March, 2017. You can find further information on the Literature and War Readalong 2017, including the book blurbs here.