Book Review by George Simmers: Another General Strike novel. Swan Song is the sixth novel in the Forsyte Saga, and the last of the second trilogy ‘A Modern Chapter’. The first trilogy had been an examination of pre-war England, and the second deals with post-war life. One character’s diagnosis is: ‘what happened to the Age—something broke and it hasn’t yet got its second wind.’

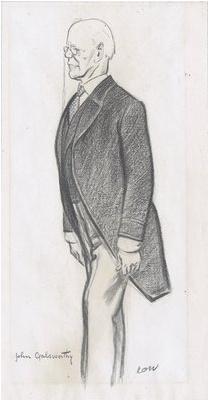

John Galsworthy by David Low.

John Galsworthy by David Low.

The Forsytes are presented as the absolute embodiment of the Upper Middle classes and in the first books they are heavily satirised – especially Soames Forsyte, the ‘Man of Property’ who marries a beautiful woman and then treats her as his possession, totally failing to understand her. Several books and forty years after the events of The Man of Property, Soames is still recognisably the same man, but England had definitely changed.

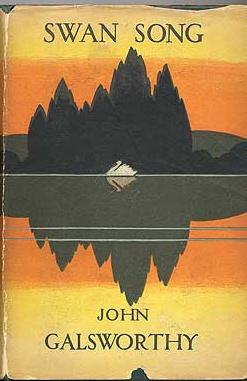

First edition

First edition

The first section of Swan Song deals with the crisis of the General Strike – the biggest challenge since the war to English security. The book presents the Upper Middle class (and the Forsytes in particular) as responding to it brilliantly.

Michael Mont (a forward-looking Conservative M.P. explicitly connects this challenge to that of the War:

In the trenches, of course, […] sentiment and hate, advertisement and moonshine, had been ‘taboo,’ and with a grim humor the Briton had just ‘carried on,’ unornamental and sublime, in the mud and the blood, the stink and the racket, and the endless nightmare of being pitchforked into fire without rhyme or reason! the Briton’s defiant humor that grew better as things grew worse, would—he felt—get its chance again now.

Jon Forsyte comes back from abroad to volunteer as a strike-breaking stoker on the railway, saying : ‘Left his wife and mother in Paris—said he’d missed the war and couldn’t afford to miss this.

Soames Forsyte’s daughter, Fleur, does what women of her class hasd done during the war, and sets about organising a canteen for the volunteers. The strike is actually welcome, as giving these characters a positive purpose in life. Afterwards, Fleur says:“I feel at a bad loose end, Michael, without the canteen.”

There is little discussion of the politics or roots of the strike; even more than in Philip Gibbs’s Young Anarchy, the strike is taken for granted as something that must be defeated for England’s sake. The nearest anyone comes to analysis is:

Excellent fellow, the miner—but unfortunately cursed with leaders. the mine-owners are in the same case. Those precious leaders are going to grind the country’s nose before they’ve done.

Afterwards, the upper classes are very conscious of having won, but the strike remains something of a mystery to them. Soames reflects:

Good old England! We’re a great people when we’re up against it!’ he thought, driving his car slowly on into Trafalgar Square. a group of men, who had obviously been strikers, stood leaning against the parapet. he tried to read their faces. Glad, sorry, ashamed, resentful, relieved? For the life of him he could not tell.

The sense of the English as ‘a great people’ seems to me to link to Soames’s walk (when feeling low) to see the large Artillery Memorial in Hyde Park.

This has statues of gunners by the remarkable sculptor, Charles Sargeant Jagger. They are not symbolic figures, but large, tough competent men, and in Soames instil a sense of the ‘real’:

the Artillery Memorial. a great white thing which he had never yet taken in properly, and didn’t know that he wanted to. Yet somehow it was very real, and suited to his mood—faced things; nothing high-flown about that gun—short, barking brute of a thing; or those dark men—drawn and devoted under their steel hats! Nothing pretty-pretty about that memorial—no angels’ wings there! No Georges and no dragons, nor horses on the prance; no panoply, and no panache! There it ‘sot’—as they used to say—squatted like a great white toad on the nation’s life.

In the time of the Strike, Soames gains comfort from the realism of the Memorial, and its message (the war’s message?) about the the ability of the English to survive.

After the strike collapses, there are occasional references, without sympathy, to the coal-miners who are still carrying on with their fruitless strike, which is causing inconvenience to others.

In the first book of the Forsyte saga, Galsworthy deliberately gives us Soames Forsyte’s marital roubles through his eyes, As he wrote in a preface to the novel:

The figure of Irene, never, as the reader may possibly have observed, present, except through the senses of other characters, is a concretion of disturbing Beauty impinging on a possessive world.

In Swan Song, the actual strikers are similarly absent. This is a novel about the impact of the Strike on a small section of the Upper classes – not an investigation into the Strike’s causes.

The strike ends about a third of the way through the book, but it still remains a condition of England novel. The main theme is the change in sexual morality, as Fleur is tempted to desert her husband in favour of her former lover Jon. Back in the 1888 of The Man of Property, the social taboos surrounding divorce were so strong that Irene is defeated, and comes back to her husband. Now things are far less certain

A sequence about horse-racing explores the theme of honesty. An upper-class crook gets away with theft and forgery because of his class connections, and seems a symbol of a less honest world.

Positively. The Conservative M.P. Michael Mond is recruited by his uncle, a vicar, into a slum clearance scheme. This is presented as positive, socially useful work. I’m not sure how aware Galsworthy expects us to be of the fact that this is the Upper Middles doing things for the working class, rather than working with them. It is very much top-down philanthropy. We are told a lot about the satisfaction the Forsytes and others get from doing it – not much about the reactions of those twho are the supposed beneficiaries

In his search for meaning in an unstable modern world, Soames goes in search of his ancestors, and finds a churchyard and parish register packed with yeoman Forsytes going back centuries – which bolsters his sense of permanence.

The novel climaxes with afire in Soames’s picture gallery, where he keeps the most delightful examples of his accumulated ‘property’. Fleur, anguished because of the end of her affair, throws a cigarette butt into a waste paper bin, where it smoulders and causes a fire. Soames fights heroically to save his precious paintings. When a fireman throws from above a Spanish painting of a woman who looks like Fleur, Fleur, suicidally, stands in its way as though welcoming destruction. Soames pushes her aside, and the painting hits and kills him. So he is killed by his property – but it’s an act of love.

He dies and it’s as though the age of the Forsytes is over. There is a huge change between the first novel of the series, where Soames is heavily satirised as the man of Property who loves his works of Art but can not understand human beings. In this novel he is still described as a ‘dry gray spirit’ and finds himans just as hard to understand – he can’t see why Fleur id possibly ruining herself by chasing after Jon – but he is viewed far more sympathetically, as a man – even though a limited man – who has retained his integrity through difficult years. Galsworthy now sees the Forsyte spirit as something able to survive difficulties – such as the General Strike.