European research and policy organizations have devoted a fair amount of attention to the rise of extremist movements and intolerance in European countries in the past ten years. Attention has been directed towards both aspects of the problem that have been mentioned in earlier posts -- rising public attitudes of intolerance, and the mobilization and spread of hate-based right-wing organizations. (The topic has also received a great deal of attention in the press -- for example, in the Guardian (link), the New York Times (link), and Spiegel (link).)

One useful report is Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination: A European Report (link), authored by Andreas Zick, Beate Kupper, and Andreas Hovermann (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2011). The study is based on survey research in eight countries (Germany, Britain, France, Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Poland, and Hungary). Particularly interesting are the results on anti-semitism, anti-muslimism, and homophobia (56 ff.). Here are the opening paragraphs of the authors' foreword:

Intolerance threatens the social cohesion of plural and democratic societies. It reflects the extent to which we respect or reject social, ethnic, cultural and religious minorities. It marks out those who are “strange”, “other” or “out- siders”, who are not equal, less worthy. The most visible expression of intolerance and discrimination is prejudice. Indicators of intolerance such as prejudice, anti-democratic attitudes and the prevalence of discrimination consequently represent sensitive measures of social cohesion.And here are a few of their central findings, based on survey research in these eight countries:

Investigating intolerance, prejudice and discrimination is an important process of self-reflection for society and crucial to the protection of groups and minorities. We should also remember that intolerance towards one group is usually associated with negativity towards others. The European Union acknowledged this when it declared 1997 the European Year against Racism. In the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam the European Union called for joint efforts to combat prejudice and discrimination experienced by groups and individuals on the basis of their ethnic features, cultural background, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age or disability. (11)

Group-focused enmity is widespread in Europe. It is weakest in the Netherlands, and strongest in Poland and Hungary. With respect to anti-immigrant attitudes, anti-Muslim attitudes and racism there are only minor differences between the countries, while differences in the extent of anti-Semitism, sexism and homophobia are much more marked.

About half of all European respondents believe there are too many immi- grants in their country. Between 17 percent in the Netherlands and more than 70 percent in Poland believe that Jews seek to benefit from their forebears’ suffering during the Nazi era. About one third of respondents believe there is a natural hierarchy of ethnicity. Half or more condemn Islam as “a religion of intolerance”. A majority in Europe also subscribe to sexist attitudes rooted in traditional gender roles and demand that: “Women should take their role as wives and mothers more seriously.” With a figure of about one third, Dutch respondents are least likely to affirm sexist attitudes. The proportion opposing equal rights for homosexuals ranges between 17 percent in the Netherlands and 88 percent in Poland; they believe it is not good “to allow marriages between two men or two women”. (13)These researchers find three underlying "ideological orientations" associated with these patterns of intolerance and discrimination: authoritarianism, "social dominance orientation", and the rejection of diversity. And the factors that work against intolerance include "trust in others, the ability to forge firm friendships, contact with immigrants, and above all a positive basic attitude towards diversity" (14).

The topic of the incidence of intolerance in European countries is also the subject of research in the Eurobarometer project. Here are two Eurobarometer reports from 2008 and 2012 that attempt to measure changes in levels of discrimination and prejudice (Discrimination in the European Union, 2008; link; 2012; link).

Also from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung is the report Is Europe on the "Right" Path?: Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe (link). This report provides country studies of the radical right in Germany, France, Britain, Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Here is how Britta Schellenberg undertakes to synthesize these wide-ranging findings:

Taken as a whole, the contributions in the present volume clearly illustrate the common features and differences within the radical right in Europe. Analyses of the current phenomenon of the various radical-right movements and a differentiated analysis of their origins are fundamental for considering counter-strategies. Obviously, there is no single, generally valid strategy that guarantees an optimal way of combating the radical right. In fact, strategies can be successful only if they match up to the specific political and social context and if the maximum possible number of players from politics, the legal system, the media, educational institutions and civil society are agreed upon them.Each country study is detailed and interesting. The France study focuses on the Front National and Jean-Marie Le Pen's success (and later Marine Le Pen's success) since the 1984 European election in gaining visible support and electoral success with 10% to 15% of the vote (84). The Mouvement pour la France (MPF) and its leader Philippe de Villiers also receive attention in the report. And the resurgence of skinheads and direct action neo-fascists like the "violence-prone street brawlers of the Groupe Union Defense" are discussed (89-90).

However, we can identify general requirements for strategies against right-wing extremism and xenophobia that form a framework broad enough to allow a European perspective. For concrete work in a particular place, this framework must be filled out with individual measures and activities specific to the situation and location. But for now, we shall now proceed to take a bird’s eye view and answer the basic questions as to what preconditions have to be created for maximum success in combating radical-right-wing attacks, parties and attitudes. (309)

The essay develops a handful of strategies for combatting right-wing movements:

- A comprehensive approach: Identifying and naming problems and strategically combating the radical right

- Political involvement: Confront, don’t cooperate

- Determining the focus: Protection against discrimination, and diversity and equality

- Allowing civil society to develop, and strengthening civic commitment

- Education for democracy and human rights

- The EU is being degraded into an enforcer of austerity measures across the continent. It is essential to restore the idea of the EU as a regional network of states that stand together in solidarity in order to promote mutual wellbeing, good living standards, tolerant societies, and democratic values that are shared by all.

- Furthermore it is vital to explain the local benefits of EU membership to ordinary people with a clear and understandable message.

- There need to be more efficient and accessible training and exchange programmes in order to decrease the distance between EU institutions and citizens.

- Diversity must be increased and a greater inclusiveness within EU institutions is required, with mechanisms to enable a much more accurate representation of the European population in EU institutions.

- Progressives should be strident in defending greater global and European integration against the often empty criticisms of right-wing populists and extremists.

- We recommend that different stakeholders collaborate with each other in a knowledge exchange in order to provide public officials with EU-wide training.

- Establishing quotas for those who are elected as candidates, by increasing leadership in minority groups, and via private-public partnerships to help promote equality in business as well as the public sector.

- Hate speech has to be monitored in the European Parliament by an independent body and the existing sanctions regarding hate speech need to be reviewed.

- Social media should be used in this effort to confront the advocacy of hatred and that a dialog should be promoted between internet providers and social media companies, examining among others the possibility of creating a new platform for non-governmental organizations and the civil society. (5-6)

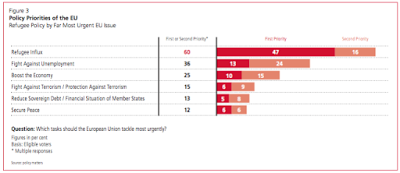

Here is a summary table based on results from all eight countries ranking the relative weight of EU priorities for EU citizens. Solving the refugee crisis dwarfs concern about other issues, though unemployment comes in as a substantial second.

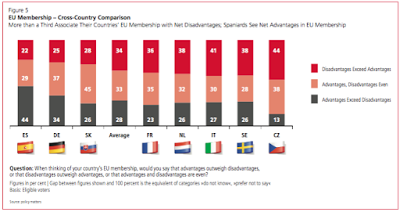

Given Brexit, it is interesting to see the relative levels of dissatisfaction with EU membership in other countries as well. An average of 34% of respondents found that "disadvantages exceed advantages" in EU membership for their country, with the Czech Republic at 44% on this question and Spain at only 22%.

These are interesting survey results describing the growth of right-wing extremism in Europe. But these studies are limited in their explanatory reach. They are largely descriptive; they give a basis for assessing the dimensions of the problem in terms of population attitudes and right-wing extremist organizations. But there is little by the way of sociological analysis of the mechanisms through which these extremist attitudes and processes of activism proliferate and grow. In an upcoming post I will review some recent work on the ethnography of right-wing movements that will allow a somewhat deeper understanding of the dynamics of these movements.