Submarine: A Review, But More, The Wall That I Keep On Hitting

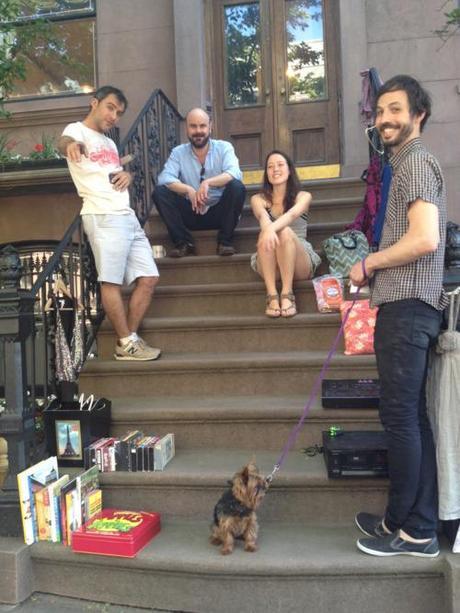

Yesterday, I spent the day on my front stoop with a few friends, trying to sell off some of Caleb’s things to make room for my own. These things included a fancy cassette player and an ASR drum synthesizer, both outmoded objects that in Williamsburg—where a generation of people raised on Wes Anderson are still trying to figure out ways in which they, too, can appropriate from the past in order to be original in the present—would have sold like wildfire. In Carroll Gardens, adult Brooklyn, people didn’t even know what they were.

“Dude, that’s for the garbage,” my friend’s boyfriend said, pointing to the cassette player.

“People still use cassette players!” Caleb protested. “Bands are starting to release their records on them again.”

“Bands that you should be ashamed of listening to,” I reminded Caleb.

Only two people even knew what the ASR synthesizer was for, in the entire ten hours that we sat outside. One was wearing a trucker hat. I could tell he was tempted to stop and admire it, but he was with his child. “Nice ASR,” he said to Caleb as he hurried past.

The other was a dude with a scraggly red beard, who was wearing baby blue cotton work-out pants without any underwear. Sitting on the benches on the sidewalk, I was confronted head-on with his penis, which dangled, untethered, on the side of his leg. His white shirt was stained, his belly slightly bloated. He would have looked right at home on Lorimer Street, but in Carroll Gardens, he looked like a mentally ill homeless guy. “Dude,” he said to Caleb. “Would you be willing to trade that ASR for some art?”

“How did you find your way over here?” I wanted to ask him. But I was too stunned by the probing head of his penis, which, like bra-less breasts in a tight white shirt, was blindingly distracting.

Eventually, he sauntered away, but not before leaving behind a business card and a flyer for his new creative collaborative. Like most “artists” today, he’s less of a creator, and more of a businessman, investing time in the evolution of his brand, rather than the in the creation of objects.

No one ended up buying either the cassette player, or the ASR machine. But they did buy most of the benches, leaving room for me in my new apartment, where I’m trying to adjust to a new conception of myself as a coupled human being.

Here, almost nothing is old. I kept about 1/10 of my clothing, my chaise lounge, and a few presents from my grandmother, who died last year.

I started this post with the intention of talking about the movie Submarine, which is about a young boy living in Wales. His name is Oliver Tate, and he is an endearing combination of Max Fischer in Rushmore, and a cutesy Jean Luc Godard. The movie is basically just a growing up tale. Max Fischer is obsessed with his self image, obsessed with a wicked girl named Jordana, but most of all, obsessed with his parents, whom he sees, in his innocent narcissism, as little more than extensions of his own oddities.

He loses his virginity, lights firecrackers on the ocean near his house, and tries to prevent his parents from breaking up over the re-appearance of his mother’s first love.

He could have been annoying, like the dude who wanted the drum synthesizer. His character also looks to outmoded things, past trends, famous figures, in an attempt to find out who he is. But for some reason, he’s not. The movie is enjoyable, and light, and sweet. It was imperfect, and kind of fell apart at the end, but it was fun to watch.

I’m making, in my own head, a lot of connections between the things that I wrote about above, but for some reason, I’m having trouble articulating my thoughts. I can’t work at all today. I can hardly sit still.

I think that what I’m trying to write, though, has something to do with losing your childhood. When you’re young, you look back a lot, to try to figure out who you are, and who you’ll become. In ways, both Submarine and the bearded hipster, with their outmoded objects, relate to that.

In this past week, I’ve shed so many of the objects that I collected, that I thought, when I was younger, made me unique. Old photographs I bought on the street. Paper lanterns from Thailand. Vintage jackets with holes in them, and cards bearing ghosts of the past. They were all privately mine, and they meant something to me.

But then I showed them, in moving, to the person I was moving in with, and all of a sudden, they seemed childish and young. I’m mourning the objects I collected that I thought made me original, and finally seeing them for what they were. Things that I thought gave me an identity.

And he showed me the objects that were important to him, and in doing so, became more foreign to me.

Now we’re both nearing a certain kind of weightlessness. But still, obsessively, both his past and my own are sticking to me.