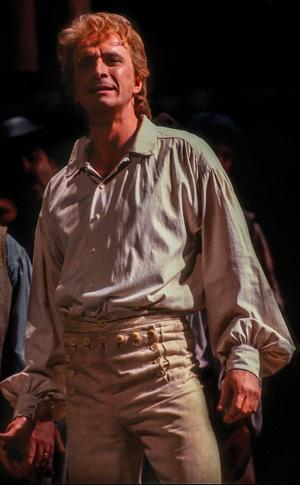

The Met Opera's production of Britten's 'Billy Budd' (Photo: Metropolitan Opera)

The Met Opera's production of Britten's 'Billy Budd' (Photo: Metropolitan Opera)

Scorching obsessions, mad love interests, infidelity, misplaced feelings, misunderstood motives. These are the kinds of things we've been talking about: something to test our ability to listen, judge, learn, and absorb; to push that operatic envelope about as far as it can go - or as far as we allow ourselves to get pushed.

Some works, by their very nature, are impossible to classify, while others stick out by virtue of their originality. Still others may or may not play well on your average stage.

One such novelty would be German composer Bernd Alois Zimmermann's 1965 gargantuan Die Soldaten ("The Soldiers"), an incredibly dense and immensely complex score (and plot) that resembles, in many respects, a nightmarish amplification of Berg's Wozzeck, right down to its female protagonist, both named Marie. This is what we mean by the term "opera on steroids." It was staged in New York at the Park Avenue Armory back in 2008.

Requiring multiple stage platforms and simultaneous action, in addition to extra-musical sound effects, we doubt it will ever see the light of day on the Met Opera stage. It's much too nonconformist. We'll call this one as we see it: A once-in-a-lifetime experience, but no more.

No, our dose of relevancy and that needed jolt to the system can be found in the modern-esque efforts of a senior citizen of Czech descent and a much lauded British composer.

This Prison LifeFrom the House of the Dead (2009). I'm a huge admirer of Czech composer Leoš Janáček's music. In fact, his concert pieces are regularly performed the world over, and with positive results. Listen, for instance, to his exceedingly sonorous orchestral showpiece, the Sinfonietta (1924), and especially to those marvelous opening brass fanfares which periodically return and conclude this lushly scored opus.

Or to the jubilant Glagolitic Mass, another striking effort (the tenor solos are exacting, to say the least). This is not at all what can be considered your normal ecclesiastical experience, but an intensely "festive, life-affirming pantheistic" expression of the human spirit, so wrote the composer.

His operas Jenůfa (1904) and Kat'a Kabanová (1921) have been performed in every major house, including at the Met, with the former work returning to the repertoire in 1974 after a 50-year absence. Sung first in English translation, Jenůfa featured Polish soprano Teresa Kubiak, American mezzo Astrid Varnay, Swedish tenor Nicolai Gedda, and Canadian Jon Vickers, whose crooning of the heroine's name, " Yen-OO-fa," threw native speakers of Czech into a fit (the accent is placed on the first syllable, YEN-u-fa).

The latter work, Kat'a Kabanová, went on to premiere, in 1991, in the original Czech language. Conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras, an acknowledged authority on Janáček's music, it starred Czech-born soprano Gabriela Beňačková as Kat'a and the legendary Leonie Rysanek as Kabanicha. Talk about authenticity! The same two protagonists, Beňačková and Rysanek, were paired again in a 1992 revival, for the first time in the original Czech language, of Jenůfa, with Madame Rysanek tearing the place apart with a roof-raising performance of the Kostelnička, or the Sexton's wife.

Another of the composer's offbeat stage works, the opera The Makropoulos Case (1926), was based on Karel Čapek's play, a veritable Victorian-era horror show, with a shadowy lead figure - the cold and beautiful opera star Emilia Marty - depicted as ageless, thanks to a secret life-extending formula. The opera had its Met debut in 1996, with diva Jessye Norman, singing in English, bringing the 337-year-old Ms. Marty to life, as it were. Later revivals included sopranos Catherine Malfitano and the Finnish Karita Mattila.

I'm still waiting for the Met to stage the delightful and stunningly gorgeous The Cunning Little Vixen (1923) or, to use its literal title, Tales of Vixen Sharp-Ears, a wonderful fairy-tale-like parable that takes place in the natural world along with the creatures that inhabit it - in particular, a clever female fox named Vixen, her mate, and, in the final scene, her little brood.

Called the most "cinematic" of all his stage works, the plot of The Cunning Little Vixen is comprised chiefly of episodic scenes in the strictly "symbolic" relationship between the Vixen and the Forester, and the endlessly repetitive cycle of life itself. But make no mistake: This is a most moving and philosophical conception. Many listeners will be hard-pressed to equate the story with Walt Disney's Bambi, but the comparisons are viable and not far from the mark. As a matter of fact, the original Vixen story appeared as a newspaper tale accompanied by cartoon strips. Imagine that! What next, an opera based on Charles Schultz' Peanuts gang? Why not! It did well on Broadway, so why not in the opera house?

A nationalist down to his bones, Janáček continuously mined his country's folk music for inspiration as early as the late 1880s. In addition to incorporating a vast amount of material into his creations, the composer went on to develop a signature form of notation, a series of sharp-edged, jagged, staccato-based motifs, injected specifically into his final work for the stage, the three-act From the House of the Dead (1928). We should make note that the composer's last four operas were written after the age of 65, which place Janáček into that elite category of older masters whose late-blooming opuses have set them apart from their earlier triumphs.

Inspired by Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky's voluminous writings of prison life (that is, his own) in a Siberian labor camp, there is no set plot, only separate vignettes scored, mostly, for male voices who are part of a collective chorus. The libretto is by the composer himself. From the chorus, individual stories emerge and are intoned as, one by one, each prisoner steps up to give a personal account of their harrowing existence and the brutality encountered in the camp. Originally in three acts, the opera was given straight, without intermission.

Their grueling existence and the pervasive bleakness of the surroundings (termed "grim, dissonant and disconnected" by reviewer Michael Kennedy in Opera on Record 2) are indicated in the opening prelude. Its monotonous repetitiveness and propulsive stridency grind on listeners nerves, almost to the breaking point. In essence, we experience the same kind of nauseatingly pointless routine, in music, as do the prisoners. "Intense," is how one critic described this searing work. One of the few moments of hope takes place when an eagle lands in the prisoners' midst, its wings damaged. As the opera ends, the eagle, its wings now healed, is lifted and released into the wild, a symbol of life-affirming continuity in the face of bleakness and despair.

The connection of From the House of the Dead to filmmaker Frank Darabont's The Shawshank Redemption should not be lost on viewers. Others may find notable similarities present in Alexander Solzhenitsyn's novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962) and his three-volume non-fiction text, The Gulag Archipelago (1973).

With a large ensemble cast headed by Peter Mattei, Willard White, Stefan Margita, Heinz Zednik, Peter Straka, Vladimir Ognovenko, Kurt Streit, Jeffrey Wells, Adam Klein, Richard Bernstein, John Cheek, Scott Scully, Peter Hoare, et al., and Finnish conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen leading the masterful Met Opera Orchestra, this 2009 production was spearheaded by debuting French director Patrice Chéreau. You will recall that the late Monsieur Chéreau was responsible for the Met's recent Elektra production and, of course, his epoch-making 1976 Bayreuth Centenary production of Wagner's Ring cycle.

Most audience members as well as viewers were caught off guard by the sheer starkness of the work and, most importantly, by the moving performances, especially those of Mr. Mattei and Mr. White. A triumph in every respect, and ultimately a validation on the struggle of individuals for survival at any cost.

Men at WarBilly Budd (1997). Survival and the enduring humanistic spirit in man are but two of the themes in British composer Benjamin Britten's seagoing saga, Billy Budd, based on a novella by Herman Melville ( Moby-Dick). The libretto was adapted by novelist E.M. Forster ( A Room with a View, Howards End, A Passage to India) and librettist Eric Crozier. Originally premiered in 1951 in four acts, Britten heavily revised the work in 1964, partitioning it into two acts, with a Prologue and Epilogue. This version met with success and the opera is now considered one of Britten's finest large-scale achievements.

Director John Dexter's classic 1978 Met production, with William Dudley's cutaway set that rises and lowers, gave audiences the impression they are glimpsing an authentic British man-o-war on the high seas. That this 1997 revival still convinces, after so many decades of use, is a remarkable testament to its durability and utilitarian aspects. Conductor Steuart Bedford, who worked alongside Britten in his last years, especially with the composer's semi-autobiographical valedictory piece, Death in Venice (1973), presided over the Met Opera Orchestra and all-male Chorus.

Set during the Napoleonic Wars era, there are boundless similarities to Patrick O'Brian's Master and Commander series of books (1969-1999) and director Peter Weir's subsequent 2003 film version, with preparations for an actual sea battle about to take place on the stage - a remarkably vivid recreation, enlivened by "real" cannon shots off the starboard bow.

The central character of Billy Budd is defined as possessing "beauty, handsomeness, and goodness." Billy's buoyant nature is preserved in descriptive language throughout and in how he's regarded by fellow shipmates, much of it streamlined for operatic purposes. The conflicts between the HMS Indomitable 's Captain Vere, moralistic upholder of order and British maritime law; John Claggart, the brutishly depraved master-at-arms, blinded by his "motiveless malignity," who lusts after Billy but vows to destroy him at all costs; and the too-good-to-be-true Billy Budd, the young and eager foretopman exuding affability, bonhomie, and loved by all (including the aforementioned Captain Vere), are skillfully juxtaposed against one another.

Exceedingly approachable as well is the music which Britten developed for this nautical tale. With a score based on old English sea chanties and folksong, this is a startlingly accessible work, tuneful and emotionally uplifting as well as vital. In this pre-HD transmission, the camerawork (supervised by veteran director Brian Large) focuses on the protagonists, especially Billy Budd (beautifully sung and acted by baritone Dwayne Croft in a blond wig), with the central theme being conformity to the norms required by the Articles of War.

Billy, an able and eager-to-please seaman, loves his work and takes to the rigors of navy life with ease and abundant good cheer, so much so that he earns the enmity of Claggart. Billy is the outsider, as Peter Grimes was in Britten's eponymously titled opera written prior to this one. Billy and Grimes are both nonconformists in a society that thrives on conformity, where the letter of the "law" is the rule, not the exception.

Discipline is adhered to, and most rigorously so. As kind, empathetic, and liberal-minded as Vere purports to be (the men nickname him "Starry Vere"), he is nonetheless bound by tradition - that is, the British Navy's code of conduct. His nemesis, Claggart (the hulking James Morris, impressive in both height and voice), is the harsh instrument of obedience to that order, the navy's blunt-edged tool used indiscriminately to beat those codes into the skulls of men pressed forcibly into His Majesty's service.

Claggart recognizes Billy for what he is: a "subversive," the one who lives and breathes outside the boundaries of the law (think Cool Hand Luke). Billy can either bend to Claggart's will (who secretly yearns to have his "way" with him) or be subjugated and cast aside. "I will break you," Claggart vows, in his bleak Iago-like soliloquy. In the same breath, Claggart can turn friendly and receptive, extolling Billy's handling of Squeak, one of the master-at-arms' slimy accomplices ("handsomely done," Claggart praises).

His face resolute, stern and sad in equal measure, Claggart is Billy's demon, the evil tempter to his boundless good cheer. Low horns accompany Claggart's every entrance (at times, stereotypically so), most prominently during his soliloquy. In opposition, Billy Budd is our Christ-like figure. Dansker (the wonderfully characterful Paul Plishka), an old salt himself, warns Billy to stay away from "Jemmy Legs." "He's got it in for you," Dansker admonishes. But Billy pays little heed, citing Claggart's praise as proof that he's about to be promoted - er, so say his shipmates. That's Billy for you, always looking on the bright side.

As it happens, Claggart forces the Novice (tenor Tony Stevenson, excellent by the way) to plant false proof on Billy's person that he is planning to mutiny the crew against Captain Vere. When the inevitable confrontation takes place in the Captain's quarters, Billy, who suffers from a stammer when provoked, is unable to verbally defend himself against the charges. Emotionally overcome, he lashes out violently at Claggart, who is instantly killed with one of Billy's blows.

As the only witness to the event, Vere is torn as to whether or not to protect Billy from the crime of striking a superior officer. Pardoning him is impossible, yet Vere secretly harbors his own unrequited (and unrevealed) passion for the young seaman. Must he be the messenger of death? Vere knows the outcome. He must uphold the king's law and British sovereignty over the Frenchies and their so-called "Rights o' Man," a phrase Billy earlier directed at his former ship before boarding the Indomitable - ultimately and tragically misinterpreted by the ship's officers.

Darkness and Light, Good vs. Evil, Beauty vs. Ugliness, Law and Duty. Which will it be? All are intertwined in this battle of wills, of man's eternal struggle to keep order in a discordant world.

Billy Budd is held prisoner in the ship's hole. Earlier, he dreamt of drowning before being awakened by the Novice. Britten and his dramatists place Billy's situation as a reenactment of Christ's Passion and suffering. Captain Vere has become both Pilate and Herod, passing judgment over Billy's fate as judge, jury and executioner.

The Christ analogy is taken a step further when Dansker visits Billy in his cell. Billy pleads with his old friend not to touch him, indicative of Jesus' charging of his disciples to "Touch me not; for I am not yet ascended to my Father." The men are planning to mutiny, Dansker tells him, in order to save Billy from hanging. But Billy will have none of it. They will be hunted down and hanged as well. Thus, Billy urges Dansker to stand down. It shall be done.

The sentence is carried out. Billy walks the plank (offstage, that is) with a noose tied around his neck. But before he dies, Billy lets out a shout: "Starry Vere, God bless you!" This is Billy's version of, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do." Lifted by two able seamen, he is hung for his crime. We, the viewers, are moved by his plight. But the opera is not yet over. Instead of a mutiny, the men, who began the opera with the chorus, "Oh, heave, oh, heave, oh heave," now imitate Billy's stammer in protest, humming the same tune but in wordless accompaniment, their mouths closed. The silence is deafening.

The now old and retired Captain Vere has the last word. In the Epilogue, he realizes his failure to save Billy - and himself. But the boy's final words to him fill Vere's soul with renewal and redemption.

The excellent all-male cast includes British tenor Philip Langridge as Captain Vere, baritone Dwayne Croft as Billy Budd, and bass-baritone James Morris as Claggart, with James Courtney as Mr. Flint, Victor Braun as Mr. Redburn, Julien Robbins as Lt. Radcliffe, Tony Stevenson as the Novice, star-in-the-making Nathan Gunn as Novice's Friend, Bradley Garvin as First Mate, Kevin Short as Second Mate, Sven Leaf as a Sailor, Thomas Hammons as Bosun, Kim Josephson as Donald, John Osborn as Maintop, Bernard Fitch as Squeak, Robert Brubaker as Red Whiskers, and the young Anthony Dean Griffey, an American tenor (and native North Carolinian) who went on to star in the Met's John Doyle production of Peter Grimes, as Arthur Jones.

A major highlight is the aborted sea battle with the Frenchies, where the fog overtakes the proceedings, amid the exhilarating chorus, "This is the moment, the moment we've been waiting for." Yes, this is the moment AND the opera we've been waiting for. God bless you, Starry Met!

End of Part Six

(To be continued....)

Copyright © 2021 by Josmar F. Lopes