Avenue (Bulimba) © Samantha Groenestyn — a little oil sketch from a landscaping adventure in Brisbane

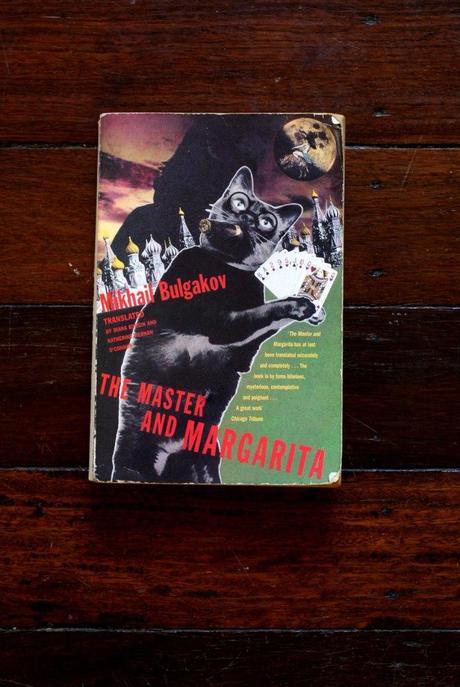

I recently read Bulgakov’s frenetic tale The Master and Margarita, and was struck most of all by how Bulgakov’s appeal to our integral Western myths proved so powerful in this story. All lightheartedness, frivolity and anti-heroes aside, the story toys with the reader’s clinging to our foundational myths, and, having been raised staunchly Christian, I found it unsettling and amazingly provocative. Bulgakov short-circuits my expectations in the story and because those expectations are built on such deeply-rooted characters and events, the effect is very confronting. The story drops a lot of little hellish jokes, interjections of ‘what the devil!’ in place of any ‘oh my God,’ but more than this, it takes the character of the devil himself and does only what Christianity suggests that he does in making him take the guise of someone appealing offering only things that human beings, easily amused creatures that we are, want. And then it conflates this playful devil with a benevolent, peace-giving power that acts discerningly and justly, not rewarding indiscriminately, not forgiving, but recognising the intentions of all and repaying the most courageous. An anti-Christianity, in a sense, that tests all, but heaps punishment on the weak, and applauds the strong.

‘It’s the speed I like,’ said Margarita excitedly, ‘the speed and the nakedness. Like a shot from a Mauser—bang!’

Any simple sympathy with Christianity will make one bristle a little at this idea—the injustice of mocking the weak, of anything positive coming from the hand of the devil. And this is just the literary power of this book. Something is ingrained in us, some moral sense that has been taught to us through our stories, through our punishment and reward mechanisms, something about ideas of innocence and meekness. Even if straying from the explicit biblical narratives doesn’t bother us, perhaps because we lack a real familiarity with them, diverting the currents of the underlying themes probably still affects us in a profound way.

While the Greek myths in paintings are less accessible to me just because of my limited acquaintance with them, Western culture owes a huge debt to our ancient Greek heritage, including the philosophies that we continue to draw on. Similarly, the Judeo-Christian tradition has built a lasting foundation for our thought, and its imagery has persisted in Western art for centuries. If our earlier art has anything over modern art, it’s that it returned again and again to the unending font of imagery that the Greek and Judeo-Christian traditions have provided us with, meaning the artist had the power to bestow an instant and deeply profound visual impression on the (often illiterate) viewer. The modern artist, if making self-directed, largely autobiographical art, has to work harder to make such a profound impact, and has to provide so much background detail, probably through words, to convey anything so dramatic. My point is this: our myths give us a language, a system of ideas, even a set of symbols that act as shortcuts in our brains, letting us tap into bigger concepts with only subtle nuances. And, further, we can not only take short cuts, but perhaps even, like Bulgakov, short-circuit that existing framework and challenge it in a way that Vatican-employed painters of the past were not at liberty to do.

Nella morte avvinti (In death thrall) © Roberto Ferri

Italian painter Roberto Ferri comes to mind—his spectacularly rendered nudes curl their superhuman forms through gorgeous forestscapes, dripping red draperies, and his paintings unmistakably echo old master paintings in form and content. Religious themes and mythological creatures bring a solemn heaviness to his work. But there is no anachronism here: Ferri’s paintings all bear the stamp of the present age in his manipulation of that age-old subject matter. Nudes are not discreet church nudes with modest drapery and strategic foliage; rather they bare their genitalia in all their sexual glory. And the seemingly ideal human forms distort into fleshy mutations, or are gorily impaled, in the visually explicit way we have adjusted ourselves to in other media. Saints and goddesses and hybrid creatures abound, but they are never trite, nor nostalgic, nor antiquated. Our traditional ideas, rather, are subjected to modern thought and to modern eyes in an extremely provocative and powerful way. The violence is palpable.

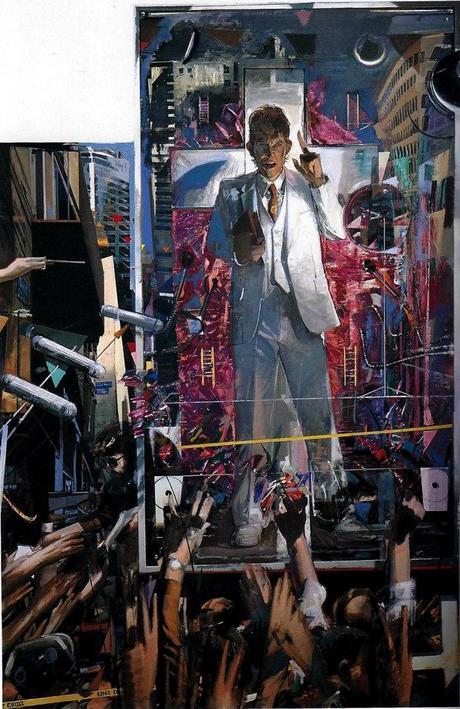

American painter Jerome Witkin has a series called A Jesus for our time which likewise rehearses a familiar theme; he clothes his well-intentioned but ultimately fragile saint in a white suit and amplifies him and surrounds him with the dazzle and noise of an electric wonderland, before depicting his shattering end. The paintings speak to so much of what we know and what we expect from a Christ character, and there is something strangely appealing in the Jagger-esque prophet Jimmy. This character triggers so many of our hopes for the world, and Witkin reaches right inside us to grab that vein and wire us in to his parable of the modern world. This is not simple symbolism and substitution of modern-day paraphernalia. Witkin really pushes this myth and distorts it in a deeply disturbing and affecting way. Witkin (p. 53-4) himself said of this series that he wanted to appeal to ‘the sense of struggle; a mythic hero who is … beaten down by the world, yet still believing in a guide.’ He comments (p. 54), ‘There’s no real church art in our century; heroes are hard to find.’

A Jesus for our time, panel II – Jimmy’s mission to Beirut (late afternoon) © Jerome Witkin

American writer Kurt Vonnegut put forward the idea, many decades ago, that the shapes of stories could be plotted as graphs and thereby categorised. He describes simple waves like ‘man in a hole’ and ‘boy meets girl,’ where a character gets into a mess and finds a way out, and where a character gets something they prize, devastatingly loses it, and fights to get it back. ‘People love that story,’ he quips—‘every time that story gets told, someone makes a million dollars.’ The story shape that most fascinated him, though, was the one that incrementally lifts a character out of a miry pit, dashes all their hopes, and at the last minute rewards them, usually by sudden and supernatural means, with off-the-charts improbable happiness—a story shape shared by both Cinderella and the New Testament. Telling, no?

I’m reminded of Alain de Botton’s insight that the news—intentionally factual, though tauntingly drip-feeding us snippets of horror in a steady twenty-four hour stream—brings us to the brink of these complex and important emotions, but gives us no way to resolve them. Our myths are often dark, confronting, and pitching good and evil forces, or blurring those moral delineations, and delving into familiar tragic territory. But as de Botton is careful to distinguish, where horror pierces us and leaves us hanging, tragedy seeks a resolution. Awful things happen to ordinary people, and the only thing that separates us from the antihero is pure chance. Tragedy helps us comprehend the darkness in the world by tracing it back to ordinary creatures, not monsters, and walks us in their ill-fated shoes. Through stories—written or painted—we can confront these deep and difficult emotions and moral questions and perhaps even come out on the other side a little wiser.

Our myths are not obsolete, and not a cheap trick. They stick us right in the heart, but only because they get at the heart of things that matter to us. They give us a way to get instantly intimate with our audience, and after that it’s up to us to try to take our audience across that emotional bridge, rather than to shatter them.

Bulgakov, Mikhail. [1966] 1995. The Master and Margarita. Trans. Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O’Connor. Picador: London.

Chayat, Sherry. 1994. Life Lessons: The art of Jerome Witkin. Second edition. Syracuse University: Syracuse, NY.

De Botton, Alain. 2014. The News: A user’s manual. Hamish Hamilton: London.