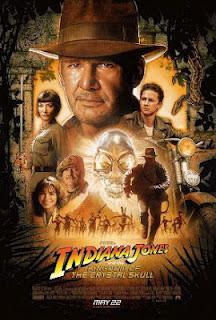

In defense of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, there is at least some kind of push to make the movie distinct from its predecessors. Where the first three films paid homage to serials of the ‘30s and ‘40s, Crystal Skull accounts for the 19-year gap between between this fourth installment in the franchise and 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade by shifting its inspirations accordingly.

In defense of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, there is at least some kind of push to make the movie distinct from its predecessors. Where the first three films paid homage to serials of the ‘30s and ‘40s, Crystal Skull accounts for the 19-year gap between between this fourth installment in the franchise and 1989’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade by shifting its inspirations accordingly.Here, the root inspiration is ‘50s-era science fiction (and its attendant Cold War subtext), which, in a way, makes the film unique, at least in relation to the other Indy movies. Instead of relics with supernatural might, the treasured objects of the film’s title are mysterious, perfectly formed skulls with strange powers, powers not of brute strength but of mental manipulation. In keeping with anti-Communist paranoia, the weapon here is the power to brainwash without fail. It’s a clever twist that didn’t get enough credit upon the film’s initial release; the only critic I can recall even mentioning it was, of all people, routine Spielberg-basher Jonathan Rosenbaum.

The film opens not with the usual bombastic, audience-grabbing stunt but with a light-hearted, rock ‘n roll-themed drag race between soldiers headed for a military base and a car filled with high school greasers and girls. The same Western expanses Indy rode through on a horse and train as a young adult now sport the freshly paved lanes of Eisenhower’s interstate system. And when the race ends and the military convoy arrives outside Area 51, Spielberg switches over to Cold War invasion terror when the soldiers turn out to be Commies in disguise, looking for deadly secrets to use against America. It’s a low-key opening for the franchise, but one that displays a refreshing willingness to grow and change. It scarcely feels like an Indiana Jones film at all, an intriguing change of pace that shows off the director’s playfulness.

And then Indy shows up. The second our archaeologist hero is heaved from a car trunk, the sheer force of his iconography commandeers the film. Spielberg only exacerbates Ford’s enduring charisma, ironically, by not showing him immediately. He instead introduces Indy by his synecdochical item of clothing, his fedora, then through a silhouette on a car door. By the time the camera twirls around to capture Ford’s aged but still grizzled face, the director has more or less served the role of James Brown’s announcer, whipping the crowd into a frenzy before throwing over to the main event. By introducing Indy through his shadow, though, Spielberg inadvertently suggests that he is a Nosferatu-like monster, come to steal away a potentially interesting, individual effort and make into the usual tat.

Indeed, Indy’s appearance marks the start of a gradual downturn in quality that lasts the entire film, sapping the initial burst of energy and creativity until Crystal Skull ultimately morphs into a pandering, listless sequel that fails to capitalize upon its ideas. It starts early: forced by the Russians to help them find an alien carcass that holds the key to their plans, Indy of course ends up in a huge chase to escape, a genuinely impressive stunt that shows Ford’s willingness to still do at least some of his own stunt work. But as he careens around the vast warehouse slamming into objects in a military transport vehicle, the camera stays behind one mangled box to reveal the Ark of the Covenant, hidden at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. It’s a trite moment, one that breaks the spell momentarily cast by the sequence and serves only to placate an audience assumed to be getting bored already.

The rest of the film generally plunders past installments for inspiration. The wry father-son dynamic of Last Crusade, as much a parody of Spielberg’s pet theme as one of its finest presentations, is presented in inverse. Now Indiana is the absent, crotchety father, made to contend with the sudden appearance of a son he did not know he had. And just as Indy’s impetuousness and hands-on approach to archeology caused conflicts with his studious dad, so too does Mutt Williams (Shia LaBeouf) represent everything Indiana hates. But where the rift between Indy and Henry Sr. played out almost as a professional and personal rivalry, making them brilliant comic and action foils, Mutt’s juxtaposition is simpler. Stacked against Indy’s encyclopedic knowledge and lifetime of academia, Mutt is a greaser dropout whose flits of archaeological know-how seem less deepening personality quirks than necessary add-ons to ensure he’s not total dead weight.

Because of this facile contrast, based in the easy humor of poking Indy for his age, Ford and LaBeouf display none of the chemistry that made Ford and Connery one of the best father-son pairings in film. LaBeouf’s attempts at swagger come off as hollow arrogance, and he lacks the presence to hold his own against Ford’s laconic put-downs. Part of this isn’t LaBeouf’s fault: the spiky energy between Ford and Connery came from an entire history Indy and his father shared off-screen. Thrust upon Doctor Jones as the son he did not know he had, Mutt is as unfamiliar to the hero as he is to the audience. Mutt feels more like Short Round than he does a son. But at least Short Round had comic timing; LaBeouf’s awkward posturing communicates none of the rebellious cool of all the ‘50s teen heroes he studied for the role. Not even Spielberg can make him a striking figure, framing the boy’s introduction through mist at a train station but making his sudden appearance instantly dull and extraneous. The camera immediately picks up on what the script did not: this character does not belong.

As the film presents Mutt as Indy’s son, it must also bring out the boy’s mother, leading to the return of Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). Probably the most beloved character in the franchise besides Indy himself, Marion should be a welcome sight, and she even avoids the damsel pitfall into which she fell in Raiders’ second half. But there’s something off about her from the moment she appears, a strange look in Allen’s face that suggests she’s so happy to be included that she might break at any moment, turn to the camera and thank Spielberg just for letting her be a part of this wonderful project. It obliterates the edge she gave Marion back in 1981, making her look about as vacant and loopy as John Hurt as a professor driven mad by the strange, thrumming energy of the crystal skulls (vaguely recalling Roy’s obsessive, alien-tweaked behavior in Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Of course, crowds flock to see Indiana Jones movies not for depth of character but for the quality of the stunts. Unfortunately, the tactile quality of the old film’s sequences has been swapped for vast, empty CGI that utterly drains Crystal Skull of the suspense and thrill of its predecessors. When the Russians open the warehouse doors at the beginning, Spielberg cuts to an extreme long shot that swoops about as the outsized enormity of the place is illuminated by truck headlights that burn as large and bright as twin suns. It shows off Spielberg’s bombast, but it lacks feeling. Compare this master shot of the warehouse to the one that closes Raiders: that film used its own trickery to make its warehouse seemingly endless, employing a matte painting that creates the illusion of a storage facility that stretches into the vanishing point. Nevertheless, even the old methods of fakery have a texture to them that the too-slick computer animation here lacks.

(That the CGI is so sloppy in Crystal Skull is surprising given the typical level of quality of computer-animated effects in Spielberg’s film, from the landmark, still-gorgeous dinosaurs of Jurassic Park to the finely detailed, artfully odd designs of War of the Worlds. Compare the undated quality of the effects of those films with a scene here of ants swarming a particularly bullish Russian soldier who serves as primary henchman. Granted, CGI faces are always hard to pull off, but try not to laugh at the utterly pedestrian quality of this shot, which looks as if it had been animated in the mid-‘90s, not four years ago.)

The most famous example of the overinflated, stake-less action is, of course, the “nuking the fridge” scene. The moment of total disconnect from the movie when I first saw it, this sequence no longer bothers me as it did. There’s no denying that the sight of Indy surviving a nuclear explosion by hiding in a lead-lined refrigerator is exceedingly stupid, the sort of thing that is clearly meant to be a gag but is then played too straight to work as a joke. But the mock suburb targeted for the test strike is admittedly funny, Spielberg and Kaminski lightening the frame to capture the treacly, bubblegum view of ‘50s middle-class comfort shortly before it is obliterated by the military-industrial complex that constructed that illusion. And though the sight of the Indy-filled fridge soaring through the air and slamming into the ground with enough force to liquefy the old man is too stupid to bear, the ending shot of Indy looking up at the mushroom cloud sucking up dust to blot out the sun is as surreal and hauntingly beautiful as anything in War of the Worlds.

For me, the more garish sequence is the epically disastrous centerpiece in the Amazon. With both Indy’s band and the Russians hunting for El Dorado, Spielberg collides the two in an extended sequence that awkwardly mashes up several distinct setpieces into one clumsy whole. The action moves from a truck containing Indy, Marion and Mutt as prisoners to their eventual escape and takeover of that vehicle and others, moves into a sword fight held across two cars, an Aguirre-esque rain of monkeys, the aforementioned bit with the ants and, finally, a trip in an amphibian vehicle down not one, but three waterfalls.

In many ways, this sequence recalls the similarly epic Bagghar sequence from last year’s The Adventures of Tintin. That film’s centerpiece was a masterpiece of mise-en-scène, an unbroken animated shot that kept piling on information into the frame until it threatened to collapse under the strain. But here, Spielberg’s direction lacks any flow; the monkeys, bullet ants and waterfalls do not clearly occupy the same space, not in the way that everything in Bagghar somehow makes sense. When Mutt gets sucked up into the tree canopies an finds the monkeys, it’s as if he’s gone to another place entirely. The same is true of the sudden appearance of the ant mounds, or the almost inevitable waterfalls.

I know some who pardon this sequence, arguing that it is meant to be taken in light jest, but the previous Indiana Jones films all achieved a lighthearted, effervescent energy in their stunts without completely tossing out the tension or a loopy verisimilitude. Can I believe natives hundreds of years ago carved a perfectly spherical boulder and somehow hoisted it into a booby trap that can detect a difference in weight seemingly by the ounce? No, but I can buy it at the start of Raiders because the direction is so exhilarating and the layout of the tomb so clear simply from a few glances. This sequence holds no weight at all, and it’s more visually incoherent than Spielberg’s handheld camerawork.

The only setpiece that really works is the nighttime grave-robbing scene where Indy and Mutt discover a crystal skull of their own. That the scene works at all is somewhat to the film’s detriment, as it is the sequence that most resembles (or rips off) the other movies in the franchise. Like similar sequences in the other films, this is a bridging moment, with Indy wallowing around some grimy, dark place looking for the next piece of the puzzle. This scene lacks the same icky factor of the rat- and bug-infested catacombs of past efforts, but the surreal slapstick of natives diving in and out of holes to torment Indy and Mutt is the only time the comedic approach to the stunts is genuinely funny and not out-of-place. Granted, it resembles a Scooby Doo episode more than an Indiana Jones setpiece, but I’ll take what I can get with this movie. I'm also fond of the effect of an immaculately preserved body vaporizing upon contact with oxygen, a delightfully gruesome aside.

I have not yet mentioned the film’s primary antagonist, Irina Spalko, played with spiky dispassion and an inconsistent accent by Cate Blanchett. Like other villains of the series, Spalko is the avaricious foil to Jones’ prosocial motives for finding artifacts. If anything, she may be the purest contrast for the hero yet, her thirst for power taking the form of a Faustian hunt for ultimate knowledge that is not too different from Jones’ quests of secular enlightenment. Blanchett’s pristine beauty makes her a striking villain aesthetically, but she combines the least memorable aspects of Indy baddies and female characters into one empty shell of a character. The problem also is that the villains in Indiana Jones movies are typically just stand-ins for a larger evil force that can be despised: ask someone who the bad guy in Raiders of the Lost Ark, and you’ll probably hear “Nazis” instead of “Belloq” or “Toht.” Commies don’t hold the same lingering allure/repulsion that Nazis do, further draining Spalko of her thin presence.

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull ends with some pseudo-scientific mumbo-jumbo about inter-dimensional beings and a hideously animated maelstrom of a flying saucer taking off, but its worst image may be its last, of the literal riding into the sunset of Last Crusade replaced by a perfunctory wedding. Like other aspects of the movie, this coda is intended to show Indy coming to terms with his age. But for a movie that tries so hard to argue that the old guy’s still got it, these concessions to maturation seem no more than light gags, instead of the criticism they might have been. Crystal Skull’s acknowledgement of its hero’s age might have been a comment on all heroes and how they do not remain frozen in their youthful triumph. That it is instead a lazy, vaudevillian throwaway only compounds the potential wasted on a return to one of the most popular film franchises in history.