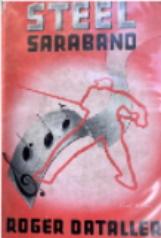

Book Review by Sylvia D: Roger Dataller was the pen name for Arthur Eaglestone, who was born in Rotherham in 1888 and started working in a steel mill at the age of thirteen. He then worked for a number of years as a miner and in 1925 published From a Pitman’s Notebook This won him a Miners Welfare Scholarship to New College Oxford which he left in 1931 with a B Lit. He returned to South Yorkshire and worked for the WEA and the extramural department of Sheffield University whilst writing works of fiction, literary criticism, drama and history as well as an account of the Rockingham Pottery which was published under his real name.

Steel Saraband is the story of Walter Haddon who was from fairly humble origins and worked shifts as a stock-taker at a massive steel works in Netherside (Rotherham?). He is not an attractive character – harsh, ruthless, devious and an ambitious man and when promoted to the role of works manager starts to throw his weight around, antagonising the workforce and making enemies. He asserts his authority by engineering the dismissal of a worker for an offense that could easily have been laughed off with an informal warning and as he becomes more confident, starts to drive the men really hard.

Haddon has been married to Freda for seven years and the couple have no children. Freda was a teacher before she married but, like so many married women at the time, had to give up her job when she became Mrs Haddon. Particularly once they have moved to a big, bleak, isolated house, close to the river, and Haddon ensures they employ a maid of all work, Freda is very much at a loose end, especially once her only close friend moves away from the town. Haddon joins the golf club, buys a car, starts inviting more senior managers to dinner. He, it is, who takes all the decisions and overrides any objections Freda comes up with. He is anxious for her to mingle with the wives of the senior managers and although she agrees reluctantly to join their philanthropic society, she feels it is pointless and that members are mainly involved for their own self-gratification.

Haddon lacks imagination and totally fails to grasp that his marriage is slowly failing, his wife increasingly convinced they have nothing in common and growing increasingly distant from him. He was becoming ‘a faintly comprehended and rather unlovable acquaintance.’ She finds company and conversation with Ralph Saunders, one of Haddon’s subordinates at the steel works. Saunders sees himself as something of a poet and starts to share his work with her and then invites her to accompany him to his WEA literary class each week. However, she is reluctant to acknowledge his growing love for her and finds her own feelings difficult to fathom. Part of her feels she has a duty make out.

The novel has a bleak ending – persistent rain causes the river to overflow, (shades of the 2007 Sheffield flood!) – with water creeping inexorably into the steelworks and the Haddon’s house. Haddon’s concern is purely to keep production going and he forgets all about his wife. It is Saunders who persuades her to leave but she refuses to go with him, realising that

Neither of these men need me, . . . They think they do – both of them – but they just don’t. Walter and his vast preoccupation with the works, the cogs and wheels with which he identified his existence – Walter would need her less than ever . . . Ralph too, with his sensitive approach to the bliss and agony of experience, could afford to forget her. For him always the self-sufficiency of art, the ultimate consolation of the artist.

Haddon arrives home to find the house awash and empty. His wife has left a note saying she is leaving him and he is totally at a loss, “But why – why? . . . ‘I can’t understand! What have I done?’

I find it difficult to judge the literary merit of this novel. In some ways it is quite a gripping read once it gets going although the first episode seems to have little relevance to the rest of the narrative. One can easily skip read all the technical descriptions if so inclined but, in their way, they are quite dramatic. There is a host of steelworks characters, all with their job title – charger, roller, fitter, turnover, timekeeper, forkman. Their verbal exchanges are in dialect but this isn’t a problem. The narrative is littered with literary references – no doubt Dataller was keen to exhibit his academic prowess and then there is the poetry which Saunders writes, presumably penned by Dataller and varying in quality. There are too some successful set pieces, particularly the episode of the works do, and the Sunday school anniversary at the Methodist chapel, the highlight of which is a rendition of Gounod’s “By Babylon’s Wave” with Haddon singing fervently. The novel is not without its touches of humor.

Dataller is best in his development of Haddon’s character – from mundane stock-taker to socially climbing works manager and his growing obsession with work, to such an extent that he is prepared to risk the safety of his staff by his neglect of health and safety warnings as he tries to maximise production. The other successful thread is the way Dataller demonstrates the stultifying existence of the married, middle-class woman in the interwar period, particularly if she has no children and no household duties to occupy her.

In 1942 Steel Saraband was made into a film for propaganda purposes in a similar fashion to Greenwood’s Love on the Dole. The film was called Hard Steel and starred Wilfrid Lawson and Betty Stockfeld. It is believed it was filmed at Hadfields works in Sheffield as the script can be found amongst the firm’s records at Kelham Island Museum. Eaglestone died in 1972 and his papers are held by Sheffield University and Rotherham Archives. There are very few copies of Steel Saraband available but Sheffield Central Library has two – one in Local Studies and one in the stacks which is available to borrow.