Welcome Back!

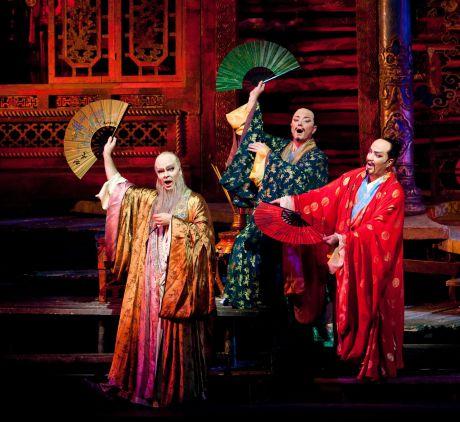

Nina Stemme as the icy Princess Turandot (Photo: Marty Sohl/Met Opera)

Nina Stemme as the icy Princess Turandot (Photo: Marty Sohl/Met Opera)

Juggling work, family, and leisure-time activities can be hard on one’s body and mind. On any given day, you may find the demands of all three battling it out for dominance. The struggle to see who comes out on top, then, defines how we deal with modern life.

Despite the daily grind, I honestly try to make a good-faith effort in setting aside a few precious moments to discourse on my favorite topic: opera. Today’s post is no exception.

After a brief hiatus, getting back to the Met Opera’s Saturday afternoon schedule is more than sufficient to recharge one’s creative juices. We’ll be reviewing the January 30th broadcast of Puccini’s Turandot, in the lavish Franco Zeffirelli production, in conjunction with the February 6th transmission of Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci, formerly given an in-depth analysis in the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2015/08/08/new-productions-of-cavalleria-rusticana-and-pagliacci-two-operas-joined-at-the-hip-part-one/.

All three pieces happen to bookend the period in European history known as verismo, or “realism” (Note: Americans experienced something along the same lines; it was dubbed “naturalism”). I’ve written extensively on the origin of this literary, artistic, and musical form, but as in all great works there’s always some aspect that might have been overlooked, hence this latest essay.

Birth of the Blues

Most scholars attach the early stirrings of verismo to the 1875 premiere of Bizet’s Carmen. While that may be the case, one must go back even further in searching for its roots: to the year 1853 and the unveiling in Venice of La Traviata by Verdi.

This work has been discussed and dissected by more musicologists than I could shake a conductor’s stick at. The point is that Verdi had chosen a contemporary topic to expend his energy and genius on.

His only other attempt at a work with so-called “modern” tendencies revolved around his choice of Stiffelio (1850), a tedious story about a Protestant minister who eventually absolves his wife from having engaged in an illicit affair. The librettist for Traviata, Francesco Maria Piave, had also prepared the verses for this unconventional three-act work. Considering the unfamiliar terrain Verdi deigned to wallow in, the opera did not go over well with either the critics or the public.

Comparable to Stiffelio, after Traviata’s own failure at the Teatro La Fenice, which Verdi attributed to bad casting and to the controversial subject of a prostitute “living in sin” with an innocent young lad, the composer never again set to music anything that smacked of topicality. Recall that Verdi insisted La Traviata be performed in contemporary clothing. No such luck! The premiere, and all subsequent productions of the opera up until 1902 or so, were staged in eighteenth-century garb, a bizarre compromise when you stop to think about it: Violetta, Alfredo, and Papa Germont, in powdered wigs and walking stick? How absurd!

The fascinating thing about Giacomo Puccini, the great man’s successor, was his inbred ability to take both contemporary and not-so-contemporary subject matter and re-formulate them to the necessities of verismo, courtesy of his unique musical language.

We may perceive Rodolfo and Mimì’s little romance as the embodiment of every young couple that has ever fallen in love. We may empathize with Cio-Cio-San’s predicament and ritual suicide, while loathing the naval officer who brought this about. We may snicker at Gianni Schicchi’s avaricious relatives by drawing comparisons to our own less-than-admirable family members.

This gift Puccini had for finding the truth in a given character or situation, particularly when they concerned his females, was a trait he shared with Verdi. Unlike the Master from Busseto, however, Puccini had an unrequited fondness for sopranos. Verdi, on the other hand, lavished some of his finest musical gifts not just on his leading ladies but on the other voice categories as well.

For some inexplicable reason, Puccini did not have much use for contraltos, basses, or baritones. Although he did manage to create some impressive adversaries in Marcello from La Bohème, Scarpia in Tosca, Rance from La Fanciulla del West, and the aforesaid Schicchi, with few exceptions — Suzuki in Madama Butterfly, Tigrana in the rarely performed Edgar — Puccini virtually neglected the mezzo. The same holds for the haughty Aunt of Suor Angelica and the rag-picker Frugola from Il Tabarro, both sung by contraltos.

Of basses, there are hardly any to speak of, outside of a brief cameo or two (The Bonze in Butterfly, Angelotti in Tosca, and Talpa in Tabarro). The best bass roles, in the Puccini canon at least, lie with two early works: the old roué Geronte di Ravoir from Manon Lescaut (which we will review in weeks to come) and the philosopher Colline in Bohème. But the sturdiest of the breed — if not the one with the most impact on the plot — resides with the maestro’s final opera, the fairy tale-like Turandot. And the basso in question is the exiled Tatar king, Timur, father to the Unknown Prince, revealed to be Calaf.

After so many depictions of “true-to-life” individuals undergoing daily struggles in highly-relatable situations, along came the older and wiser Tuscan melodist with a dark “Chinese” fable of death, violence, retribution, decapitation, torture, suicide, remorse, and finally all-out amour.

What had changed for the composer during the intermittent years between his writing of Manon Lescaut and Il Trittico, to result in the uncharacteristic culmination of Turandot?

Perhaps reality itself had set in.

After the string of successes that followed Cavalleria and Pagliacci, to include Giordano’s Andrea Chénier and Fedora, Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana and Adriana Lécouvreur, Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei Tre Re, and such associated oeuvres as Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini, Leoni’s L’Oracolo, Louise by Charpentier, and Tiefland by d’Albert, audiences began to grow weary of “real life” stories tinged with the utmost tragedy.

The cataclysmic conflagration, branded “The Great War,” had devastated a vast swath of the European continent, taking with it, to quote author Erich Maria Remarque, “the flower of German youth.” Feelings and attitudes were altered by the prolonged conflict, in addition to faith in established institutions and traditional methods of addressing social and economic concerns (see the related link concerning Alban Berg’s Wozzeck: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2014/07/21/werther-and-wozzeck-the-poet-and-the-peasant-two-big-ws-at-the-met-conclusion/).

A confirmed pacifist, Puccini would rather have made love than war. Sadly, after hostilities had finally ceased he was forced to leave his longtime residence of Torre Del Lago, by the shores of placid Lake Massaciuccoli, to live in nearby Viareggio. Ever on the lookout for fresh material and untested themes, for inspiration Puccini frequented the theaters of London and Berlin, read endless treatments of plays, novels, and libretti, and pondered wearily over a variety of subjects for years at a time.

According to biographer Mosco Carner, “a conventional sentimental melodrama no longer attracted him and he wished to ‘strike out on unbeaten tracks.’” Yet the same old, nagging self-doubts remained — that is to say, his inability to make up his mind about what to work on. Sometime around 1920, Puccini’s librettists Renato Simoni and Giuseppe Adami, stung by the composer’s constant rejection of their previous ideas and efforts, suggested he adapt a dramatic five-act fable by the Venetian playwright Carlo Gozzi. It was called Turandotte.

Gozzi versus Goldoni

By happenstance, Gozzi’s fantastical eighteenth-century output, which influenced the German romantics Goethe, Schiller, Schlegel, and E.T.A. Hoffmann, was ripe for revival. They embodied the “most vital expression of the comic spirit in Italian drama and, in particular, regarded the Venetian commedia dell’arte as the living link with the period of glory and splendor which [Gozzi’s] native city had enjoyed in the past” (Carner, Puccini: A Critical Biography, Second Edition, p. 456).

In one of those artistic coincidences that only history could have foreseen, the trend for popular farce that Gozzi excelled at had been corrupted by the introduction of improvisation and buffoonery on the stage, with episodes “devoid of human and literary interest.”

In contrast to this occurrence, rival playwright Carlo Goldoni proposed to “create genuine comedy, a comedy with characters drawn from real life, human beings with natural emotions and behaving in a natural way, instead of caricature and horseplay indulged in by the stock figures of the commedia” (Carner, p. 457). Thus the antecedents of the landmark verismo movement had firmly established itself with Goldoni’s visionary aim of substituting “literary drama for low-class entertainment.”

It fell, then, to Puccini and his librettists to force the pendulum back in the direction of Gozzi and away from the blood and thunder dictates of Goldonian “realism.” Oh, the blood and the thunder were still intact, make no mistake about that. But in Turandot, the commedia dell’arte characters — the chief cook and bottle washers Ping, Pang, and Pong — would now espouse a strictly philosophical bent, adhering somewhat to faux Chinese sentimentality yet upholding the traditional Italian elements.

The brilliance of Puccini’s conception, in Carner’s words, was in cloaking these figures “with a sadistic streak,” at the same time allowing them to indulge “in macabre humor” and snide comments about the state of their lives within the realm. In addition to which Puccini gave the trio “more humane feelings, as in the scene of Liù’s death; and in their nostalgia for the serenity of country life” (Carner, p. 466-67), much as the composer himself had so fervently expressed in his frequent correspondence with friends, relatives, and companions.

In the end, for him there was no escape from reality. The harsh lives of Europe’s citizenry, climaxing in the rise of Fascism amid such strongmen as Mussolini in Italy and Stalin in Soviet Russia (later, Hitler in Germany), were unintentionally ascribed to the icy Princess Turandot and her bloodthirsty band of followers. Mob rule, as witnessed during the French Revolution, had upset the “natural order” of things, including that of the ruling classes.

In the case of Puccini’s final opera Turandot, a slave girl’s daring self-sacrifice and an Unknown Prince’s unquestioned ardor melted hearts and altered mind-sets — a barbaric tale with a happy outcome for once.

In truth, it took a second world war to combat the evil forces unleashed upon society. Puccini passed away in 1924, but not before he saw Mussolini become prime minister, and the Italian province expand into North Africa. Unable to flee the physical confines of his own existence, the melancholy composer orchestrated his flight from reality via the rich tapestry of a fairy-tale landscape where true love conquers all.

“We are such stuff as dreams are made of.”

(To be continued…)

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes