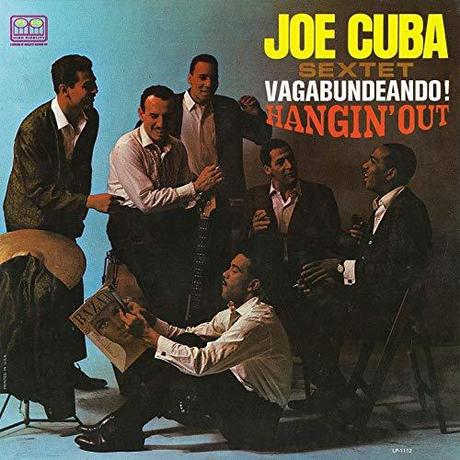

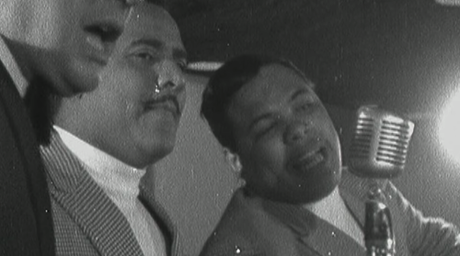

In the summer of 1966, The Joe Cuba Sextet played a show in Asbury Park, a small seaside town in New Jersey known for its beachfront properties and country clubs. “It’s all rich people out there,” Joe Cuba said in the recent music documentary, We Like It Like That. “I don’t know if you know how rich people dance, but they hardly dance. They don’t want to break a sweat! They’re just there for something like a charity event, so when they’re on the dance floor, you have to play very, very slowly.”

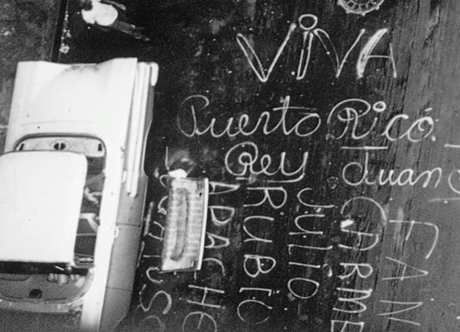

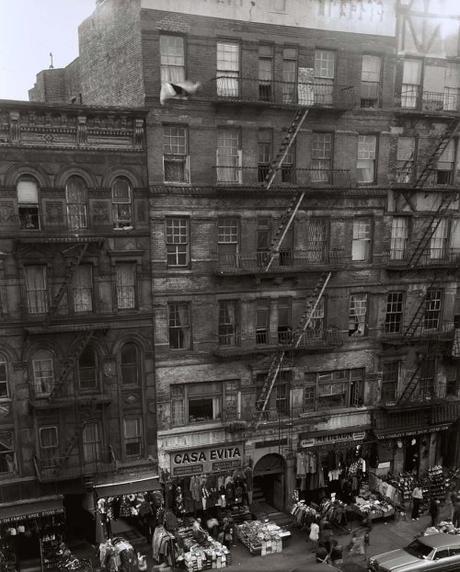

At the time, the NYC-based band was coming off their first crossover hit, “El Pito,” which was popular with Latinx and black audiences. The song’s chorus, a chanting of “I’ll never go back to Georgia,” was borrowed from Dizzy Gillespie’s 1947 Afro-Cuban jazz song, “Manteca.” The band coupled it with Latin-tinged piano lines, frenetic hand claps, and a clave rhythm. For a while in the 1960s, the song’s signature whistle would drive older NYC residents crazy as young people used it as a clarion call from Spanish Harlem to the South Bronx. Just five quick toots and someone across the street would invariably clap their hands and sing, “I’ll never go back to Georgia! I’ll never go back!” David Gonzalez from The New York Times wrote of the fans: “Of course, the farthest south most of these guys had ever been was Delancey Street to buy their Playboy loafers.”

That night, in New Jersey, Joe Cuba and his band were trying to coax a wealthier, white audience onto the dance floor when Cuba came up with a new chorus: “Beep beep, ahhh! Beep beep, ahhh!” The lyrics are largely nonsensical — a mix of Nuyorican and soul food items (“Cornbread! hog maws and chitlins! Cornbread!”) and shouts on the chorus (“bang bang!”) — but the package proved irresistible even for a bashful crowd. Later, when the band played in front of a largely black audience at midtown Manhattan’s Palm Gardens, they broke out the lyrics again, sped up the rhythm, and introduced a funky piano vamp. Almost instantly, the crowd sang along. “They were like ‘Oh shit Joe, God damn! She freaks, ahh, she freaks, ahh,” Cuba said of the night. “Bang Bang” wasn’t the first Latin-soul crossover song of its kind, but when more than a million people — black, white, and Latinx alike — bought copies of the single, it all but inaugurated one of the greatest American music genres: boogaloo.

Born in Spanish Harlem in the 1960s, boogaloo reflected the complex interplay between New York-raised Puerto Ricans and African Americans at the time. This music is a multicultural stew of Cuban cha cha cha, American blues, and African R&B. The lyrics are a bilingual blend of English and Spanish. Noted Latin music expert, René López called it “the first Nuyorican music.” For the short time it lived, boogaloo was not only about the changing taste of a younger generation, but also a way for Cuban, Puerto Rican, and black teens to explore their social and political identities.

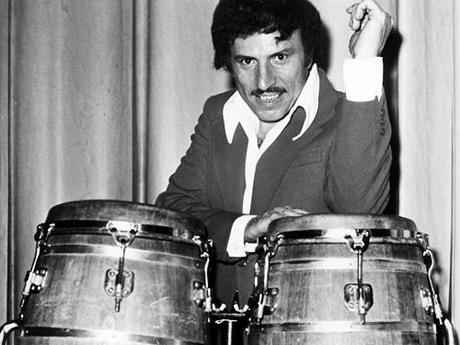

If you were an older person living in NYC during the 1950s, there’s a good chance you listened to mambo, an Afro-Cuban music style with heavy jazz influences. Mambo titans included figures such as Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez, and Machito. The big band sound is quick paced and exciting, but it didn’t connect with young people. For them, Mambo was their father’s music — they preferred the sounds of Motown, doo-wop, R&B, soul, and rock ’n roll on the radio. So, when they started making music, they came up with boogaloo and the related Latin soul styles.

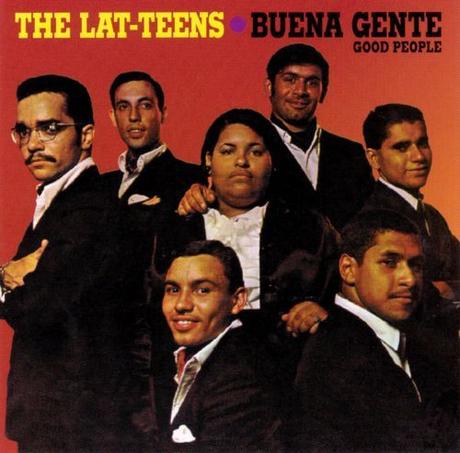

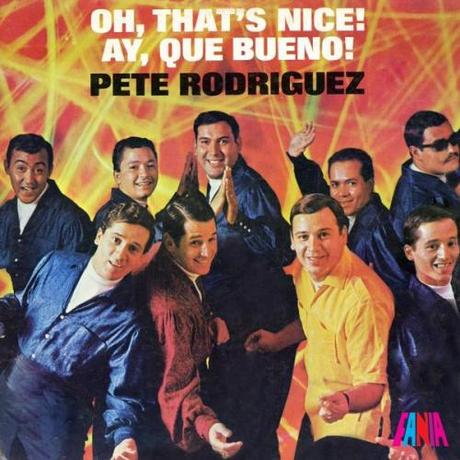

You’re probably familiar with some of this genre’s most famous hits. In Spike Lee’s semi-autobiographical film Crooklyn, RuPaul gets down in a bodega to “El Pito.” Pete Rodriguez’s irresistible, cha cha cha hit “I Like It Like That” makes an appearance in Joe Favreau’s ode to food trucks, Chef. The creeping Latin soul groove on Willie Bobo’s “Fried Neck Bones and Some Home Fries” is a clear inspiration on Carlos Santana (and one of my favorite songs in this genre — a must listen). These songs feel romantic, revolutionary, and dancefloor-ready, which is why they’re so deliciously good even today.

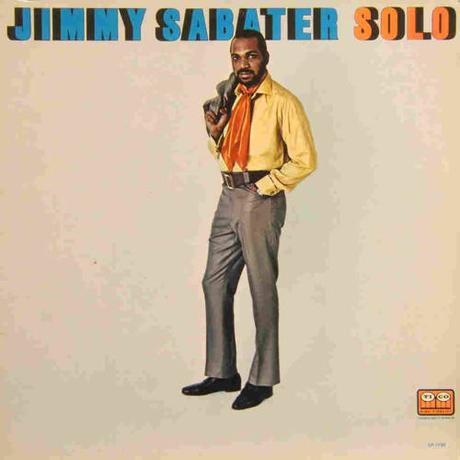

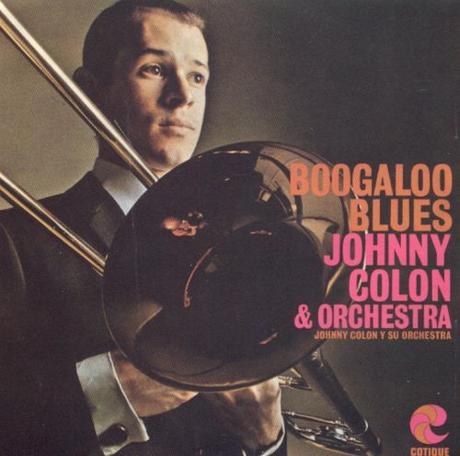

Boogaloo wasn’t the only thing to break from tradition in the 1960s. Coming at the dawn of a new political age, young people didn’t want to listen to the same music as their parents — or dress like them. The ‘60s is the first time when suits started to fade from daily American life. “When I started, guys in big bands all wore uniforms,” says Fania recording artist Tito Ramos. “Now people were in jeans and comfortable clothing. You didn’t have to dress up to be part of our music. Asking someone to wear a suit to a music show was like asking them to wear a tie to the beach.” Johnny Colon, who came up the impossibly smooth, loungey hit “Boogaloo Blues,” was one of the last holdouts. “I tried to wear a suit and tie for as long as I could, because I’m fuddy-duddy like that, but even I had to submit eventually,” he admits.

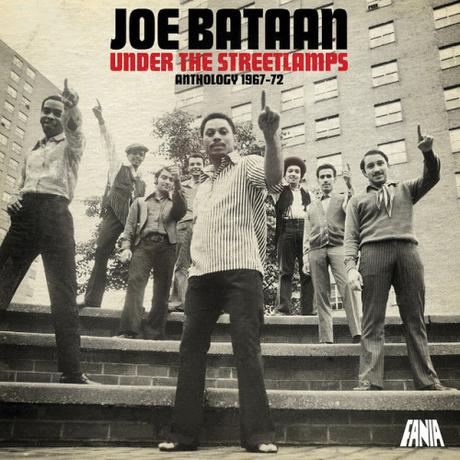

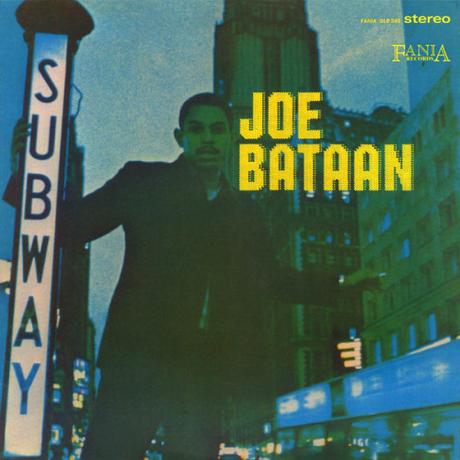

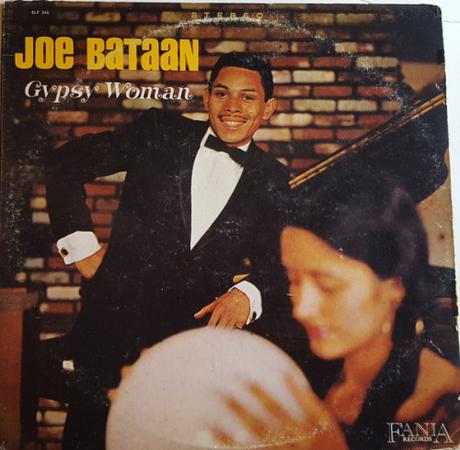

This new attitude is perhaps best captured by Joe Bataan’s soulful song “Ordinary Guy,” where he sings: “I don’t drive a beautiful car/ and I don’t own an elegant home/ ‘Cause I don’t have thousands to spend/ or a seaside cottage for the weekend/ I’m just an ordinary guy you left behind/ ordinary guy you left behind.” Bataan, the Boogaloo King, came from the sort of humble beginnings he croons about in that song, but his life has been anything but ordinary.

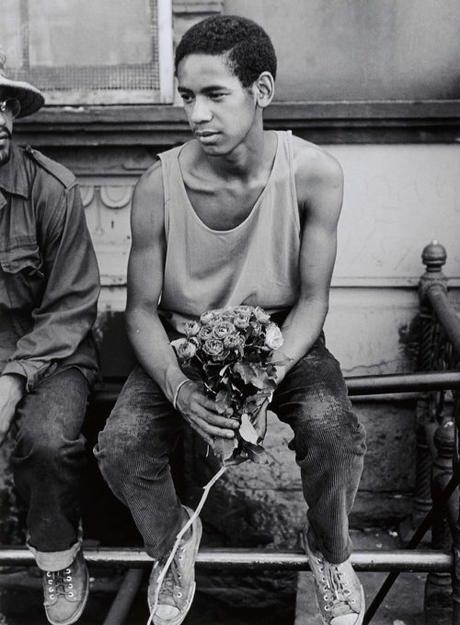

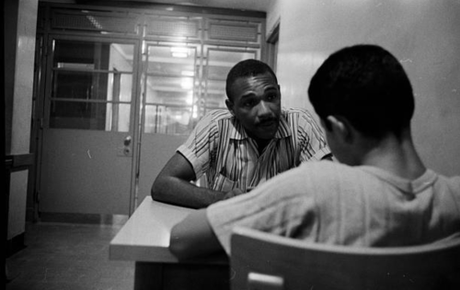

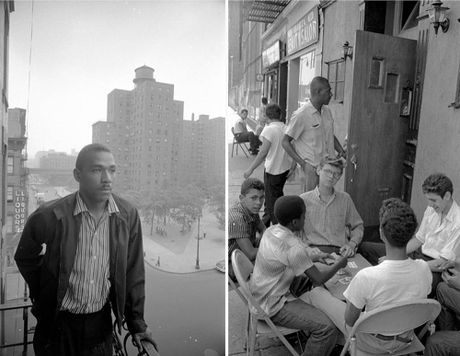

A self-described mestizo, Bataan grew up in Spanish Harlem on 103rd Street and Lexington Avenue. As a child, he dreamed of one day attending Howard University, but by high school, he was mixed up with a local Puerto Rican street gang known as The Dragons and on his way to a juvenile corrections facility. By the age of 18, he found himself standing in court with a rosary in hand. Bataan was stunned when the judge sentenced him to five years in an upstate maximum security prison for a stolen car charge. “I thought I couldn’t do it,” he said in a New York Times profile.

Upon his release, Bataan returned to his love for doo-wop and went to visit some friends at a band rehearsal. The band’s leaders, however, didn’t want anything to do with the ex-con and asked him to leave. Bataan was incensed. He vowed to start his own music group but didn’t know how to play any instruments (his mother, who washed laundry for a neighbor, also couldn’t afford music lessons). So Bataan taught himself how to play. He found a pair of pianos in a local church basement and junior high school. Through trial and error, he learned about progressions and the importance of the clave, the five-beat pattern that serves as the foundation for various Afro-Cuban music styles. After learning how to play, he commandeered an existing band of high school musicians.

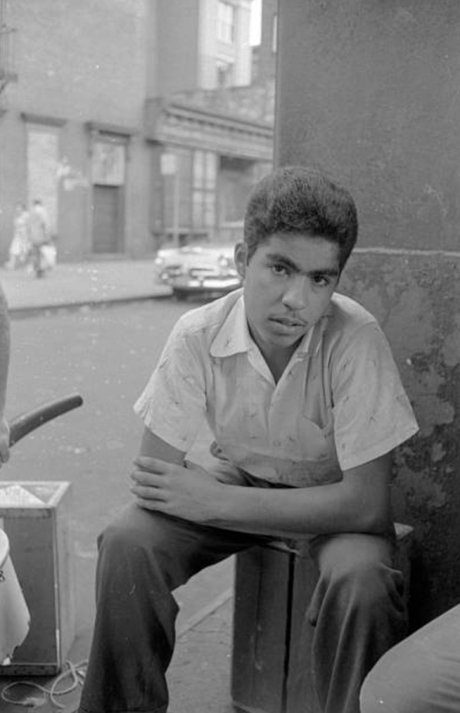

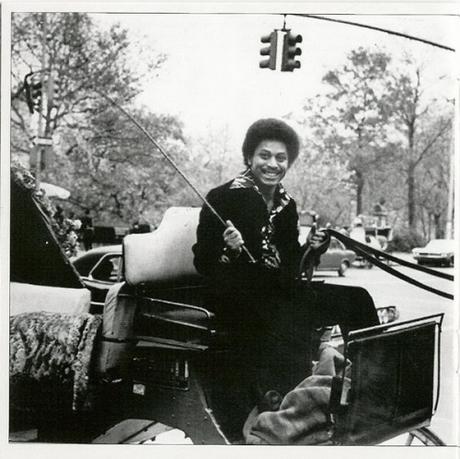

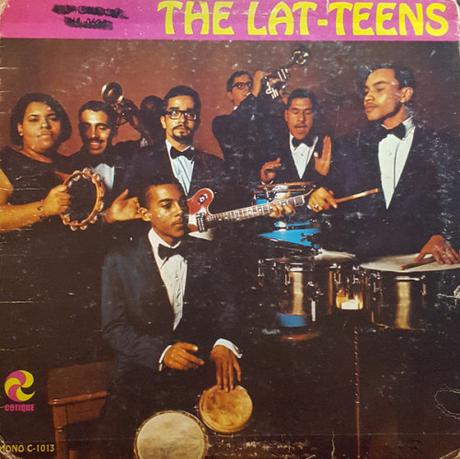

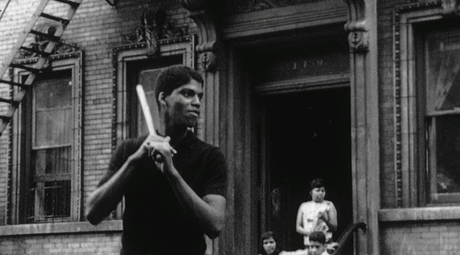

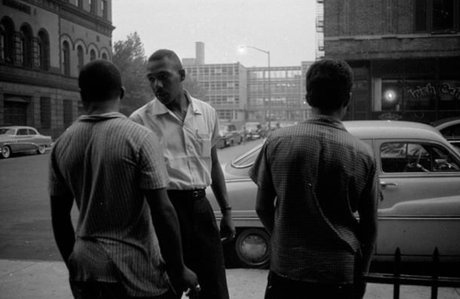

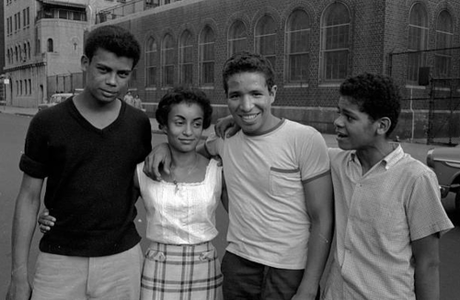

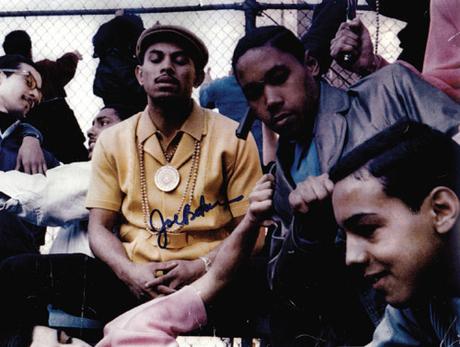

Bataan remembers how the band initially didn’t want anything to do with him (much like the doo-wop group), but he took out a switchblade, approached the group, and stuck the knife in the piano. They acquiesced. “That’s how we did it back in the day,” he laughs. The band, pictured above, would later be known as Joe Bataan and the Latin Swingers. They were the youngest group in Latin music with Bataan at 22 and the others around 13 or 14. The photo was taken in front of Manhattan’s White Park, where many youths would hang out at the time. “That’s how we dressed back then,” Bataan says of his double-knit ensemble and gold chains. “We were wearing gold chains and beaded necklaces before anyone even started thinking about them in the ‘90s.”

Bataan tells me that, during this time, guys in his social circle looked up to singing groups such as The Flamingos and The Heartbeats, where black musicians dressed up to perform. But increasingly, for a younger generation, suits were only worn to church and on fancy occasions. “We were just getting out of church mode,” he says. When they did wear suits, it was almost always charcoal worsteds with highwater pants cut so they could show off the color of their socks and the tops of their sleek, black leather wingtips. Bataan humorously recalls:

We used to go to Orchard Street to buy our suits. That’s where you could bargain. So, you’d go in and they’d tell you a suit is $40. Then you’d pretend to walk out and they’d say ‘don’t leave, don’t leave.’ You’d walk back and they’d offer it to you for $37. Then you’d pretend to walk out again and they’d repeat the process. By the end of the day, with all the walking back and forth, you could get a suit for like $25. The jacket would be a size larger than what you were supposed to wear, but they would tell you it fit well and of course, you’d believe them.

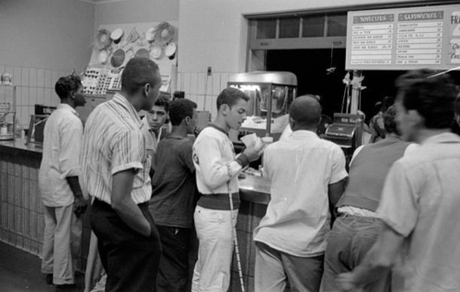

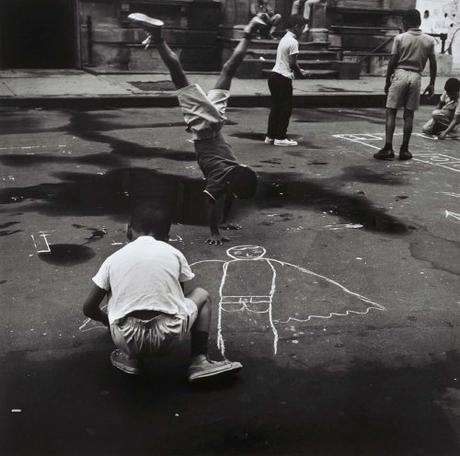

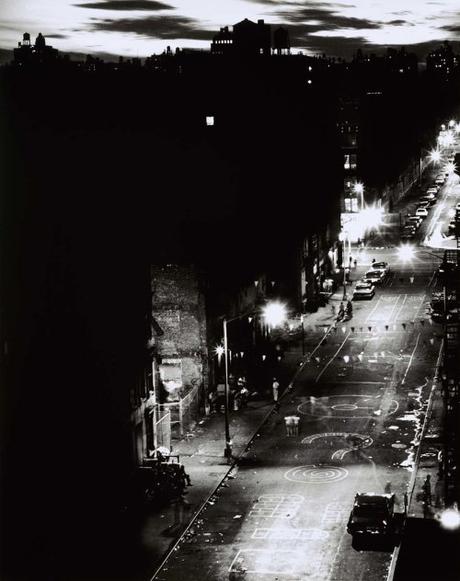

When they weren’t in suits, guys wore knitted shirts and slim-straight Lee jeans, which were cuffed at the bottom show off their red socks and Pro Ked sneakers. The summer months were all about Ban-Lon sweaters, pique cotton polos, and white t-shirts, the last of which were sometimes rolled up at the sleeves and fitted with a pack of cigarettes. If the weather got too muggy, as it often does in New York City, Bataan says they went bare-chested. “It was a different time back then,” he recalls. “We lived in a community where everyone knew everyone within a radius of one mile. We ate together, danced together, sang together. It was like family.” On those days, some traded their jeans for cotton drill chinos, which they picked up at the local military surplus store.

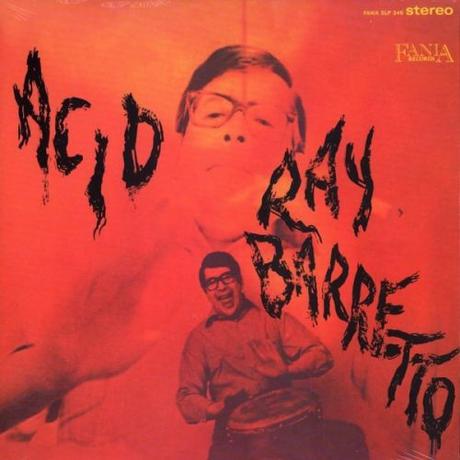

For a time in the 1960s, boogaloo was big. It came out of the projects and flooded the airwaves and dancehalls across America. By the end of the decade, however, the music style was all but dead. Some speculate the music had run its course with hits such as “Boogaloo Blues,” “I Like It Like That,” and "At the Party.” Others suggest it was a conspiracy on the part of Latin music purists who never liked the youthful boogaloo sound in the first place. They say that, with the help of label powerhouse Fania, old-school traditionalists were able to pressure clubs and promoters to push boogaloo artists off concert bills. By the 1970s, the genre was eclipsed by salsa. The purists won.

This is all a long way of saying that, this summer, I want to dress like someone attending a Latin soul concert somewhere in NYC during the 1960s. The music is chock full of style inspiration — this is the sound of muggy streets and mid-century cars, classic high-top sneakers and slim-straight jeans, knitted shirts and Caesar haircuts. Few eras have done warm weather style so well.

Certain brands and stores will be natural go-tos for this sort of look. Self Edge, Levi’s Vintage Clothing, Bryceland’s, and Runabout Goods all specialize in this dressed-down mid-century style. LVC’s 1966 501s are faithful reproductions of the jeans someone would have worn during that decade. Old photos of Spanish Harlem show people in Barracuda Harringtons and simple, striped shirts. Runabout Good’s Spectator and Drake’s blouson can be worn for the same effect.

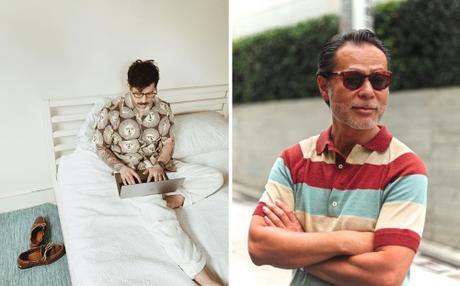

Much of this look, however, centers more on shirts than outerwear (naturally, given the season). Textured, breathable button-ups, often made from a woven dobby, would be really useful for this style. Smock Man, Indigofera, Monitaly, Séfr, and Frescobol Carioca have some handsome options this season, which you can tuck underneath a Wallace & Barnes zip-up knit if it gets cold. CMMN SWDN is a little more open-weave than I’d prefer, but you could layer it open over a vintage-styled t-shirt. I also like the patterned shirts from Universal Works, House of St. Clair, Runabout Goods, Billy Reid, Gitman Vintage, Tony Shirtmakers, Wallace & Barnes, Hartford, Dries Van Noten, and Chimala. The magnificent, sun-print, camp-collar shirt, pictured above, is slated to come out later this month at Freeman’s Sporting Club (my body is so ready).

Polos are trickier. Run-of-the-mill options from Lacoste and Ralph Lauren may hew too close to business casual. Instead, I would look to the more distinctive styling of Berg & Berg, Beams F, Canali, Stoffa, Mr. P, Altea, and McLauren. Details such as a unique collar or banded hem will make these look less like the polos you see at Hilton retreats. The Golden Closet also has a vintage polo James Gandolfini wore on-set for his role as Tony Soprano, but you need Soprano-levels money to afford it. For shoes, consider Pro Keds, JM Weston 180s, Lof & Tung black grained derbies, or even a pair of leather woven huaraches. Finish everything off with a pair of Clubmaster sunglasses.

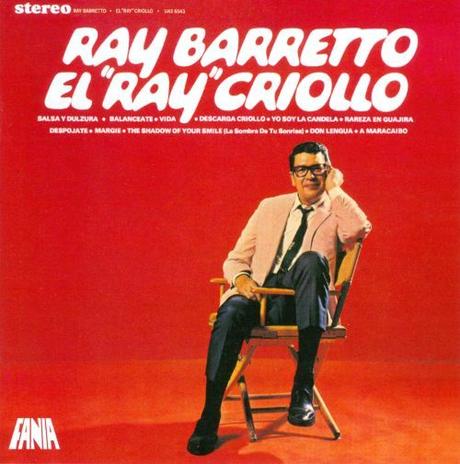

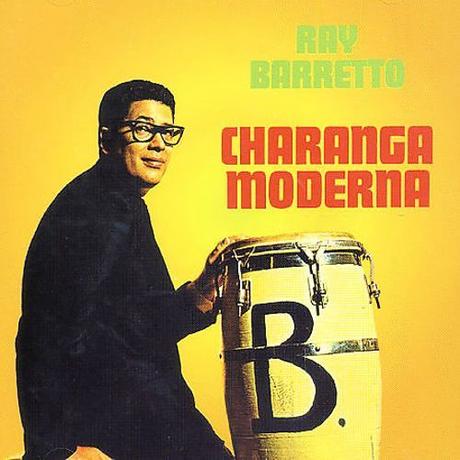

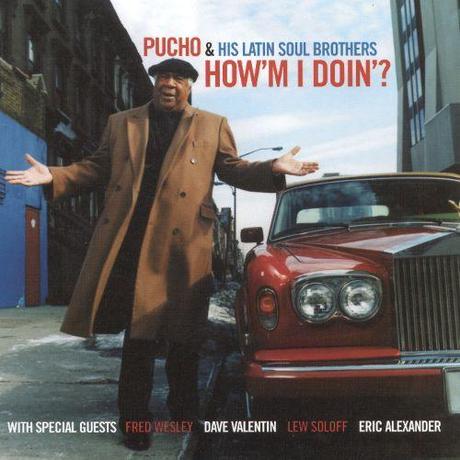

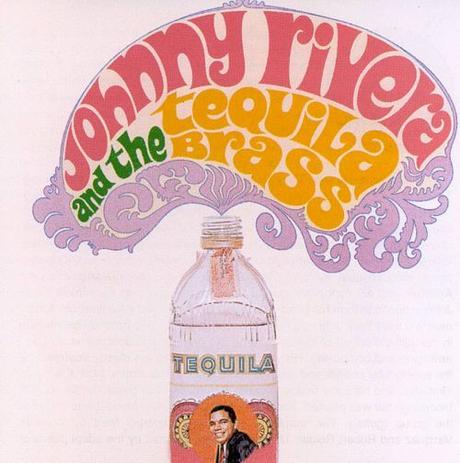

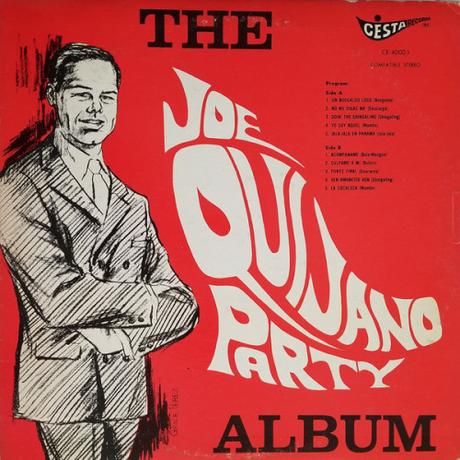

Mostly, I recommend listening to some hits from Joe Bataan, Ray Barretto, Joe Cuba, Pete Rodriguez, Richie Ray, Willie Bobo, Ray Lugo, and other Latin soul artists so you can feel your way through the style. My friend Oliver Wang maintains one of the best music blogs around, Soul Sides, which has a deep archive for boogaloo and Latin soul. Pablo Yglesias also published an excellent book titled Cocinando!, which covers 50 years of Latin album cover art.

(Special thanks to Joe Bataan for taking the time to chat with me for this post, and to Oliver for putting me in touch with him. Bataan is currently shopping around for a publisher for his autobiography. You can keep up with him through Facebook).