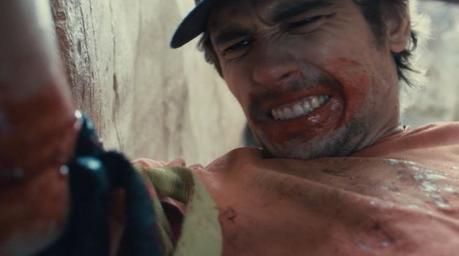

There are a lot of valid criticisms of 127 Hours. Some of the pieces don’t really work, for instance, and some of the cutting is a bit too quick. But when you get to the ending, with Sigur Rós playing over Franco’s withered body, it’s still hard not to just weep. Somewhere in this mash-up of brilliance and misdemeanor, there is the (in)famous arm amputation sequence.

For those unfamiliar with the film, 127 Hours is a 2010 Danny Boyle production based on Aron Ralston’s memoir Between a Rock and a Hard Place that recounts his fated trip in 2003, when he became trapped by a boulder in an isolated slot canyon in Robbers Roost, southeastern Utah. Eventually, and now famously, Ralston forced himself to amputate his own right arm in order to find help. It’s a harrowing true story and the film does justice to the event, funneling the narrative through each personal trauma (physical and emotional) that would arise during the laborious process of death.

As a big fan of Boyle’s past work, I was excited to see what he could accomplish with this frame-work. I heard many accounts of the arm sequence and really anticipated seeing it and experiencing it for myself. It’s a dramatic moment that many spoke of being as being an effective reproduction of what Ralston must have endured. We see it. We feel it. Obviously, I was intrigued.

So, how actually does Boyle accomplish the transfer from screen to body? It’s a very smart move: one sound. He pairs the action with a precise sound that is unlike anything I had ever heard before or since.

The images are of course visceral and Franco’s acting is terrific, but we know it is fake. Obviously Franco is not cutting his arm off. Yes, this did actually happen, but we are not seeing footage of it actually happening. So, Boyle uses a sound that is very difficult to describe (my best approximation is a cross between nails on a chalk board and a taught wire being struck) to translate what is being felt, every time a nerve is touched.

When I finally saw the film I was blown away by this choice. It is some of the most effective cringing I have endured in a film that is not the result of a simple gross-out factor. It is damaging to the viewer and makes it impossible to remember that this is not real. It is real. It damages the viewer’s senses and, when combined with the fakery of replication, it becomes a mash of over-stimulation.

Over the years, I’ve been increasingly impressed not only by Danny Boyle’s architectural filmmaking, but his use of sound as an active participant in the narrative. 127 Hours is certainly not his strongest film, but I’d say this is at least one of the top five moments he has put to screen.

I have yet to shake it. People weren’t lying when they said the scene is difficult, but I continue to look upon it with admiration because it is not difficult due to an authentic replication. It is difficult because without the gimmick of 3D, Boyle managed to put the damage into your seat. He managed to pull you into the pain and feel it no matter how much it hurt. For a few brief instants, it is impossible to remain distant, feigning viewership, and we are instead jettisoned into the moment.