I thoroughly enjoy teaching them. They are the students that constantly challenge me to be a better teacher.

We realized in the first year we offered the class that traditional instruction just doesn't work for them. We also realized that the Fs over 50% of them received that first year were for homework completion, and not for what they actually knew and understood. We had to do something different to not only find out what they knew, but also to get them to learn.

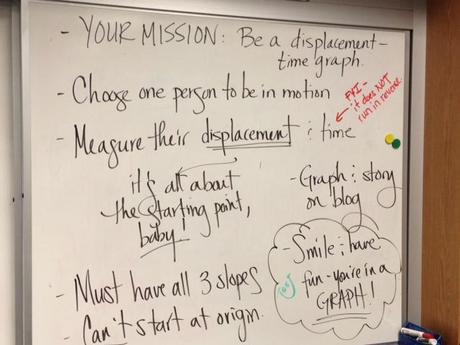

This is why I do goofy things like have them get up and be a displacement-time graph. Below is all they get at the start of an assignment (I should really write this up in an actual document some day, huh?):

I could have given them a ton of worksheets to do that contained all sorts of distance- and displacement-time graph goodness; in the past, I did. But students were just memorizing the graphs--they were just memorizing what the positive, zero, and negative slopes meant. They didn't understand the "why" of any of those slopes. And, unfortunately, that's what most worksheets tend to do--they tend to teach the rote skill without the meaning behind the skill. And that's not what my Physical Sciencers need--they don't need another worksheet to teach them another skill they didn't really understand.

I could have given them a ton of worksheets to do that contained all sorts of distance- and displacement-time graph goodness; in the past, I did. But students were just memorizing the graphs--they were just memorizing what the positive, zero, and negative slopes meant. They didn't understand the "why" of any of those slopes. And, unfortunately, that's what most worksheets tend to do--they tend to teach the rote skill without the meaning behind the skill. And that's not what my Physical Sciencers need--they don't need another worksheet to teach them another skill they didn't really understand. I wanted them to truly know, understand, and be able to do, not memorize and forget. That's where my "be a graph" activity came from, so students could learn how to really interpret motion graphs. To truly see and interpret what the motion graph is trying to tell them about an object's motion, they had to be the motion graph.

It's not a perfect activity, but it generates a lot of "OHHHHHHHs" and "Wait a minute--how could that bes" and "No I think YOU'RE wrong about what this graph looks like--let's go ask Mrs. Es." It produces a lot of beautiful discussions that are educational music to my ears. It gets students up, moving, and learning, and it looks like this:

Measuring while trying not to step on the meterstick. Also, learning how to use the metric side.

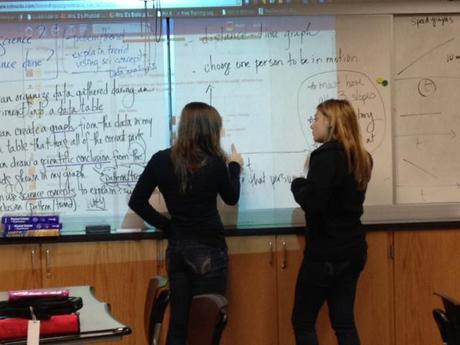

Measuring while trying not to step on the meterstick. Also, learning how to use the metric side.  Two students discussing their movement ahead of time, predicting what their graph might look like.

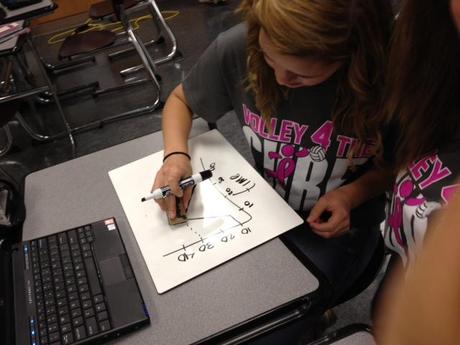

Two students discussing their movement ahead of time, predicting what their graph might look like.  Whiteboarding out their graph ahead of time before graphing it in Google spreadsheet. Yay self-checking! So how well does this work? On the formative assessment I just gave, they are nailing it. But it's more than just about some questions with pretty graphs attached to them on an assessment. It's about students experiencing the true process of learning, and about learning how to learn. Believe me, many groups had to (grumpily and with much eye-rolling and dramatic sighs at yours truly) back up and redo their measurements several times because their graph didn't make any sense at the end. (A lot had themselves moving backwards in time or back to their starting point when they really hadn't gone back there. But if they hadn't actually been the graph, they wouldn't have had their "this isn't right" spidey-senses tingling. When doing a problem on a worksheet, they have no frame of reference for realizing what they have produced isn't right.) Failure was built in to this activity, but it was essential that they experience that--because failure, a little struggling, and fixing are so crucial to the learning process. The payoff is worth it, however. Check out what a few of my students had to say to me during and after the activity:

Whiteboarding out their graph ahead of time before graphing it in Google spreadsheet. Yay self-checking! So how well does this work? On the formative assessment I just gave, they are nailing it. But it's more than just about some questions with pretty graphs attached to them on an assessment. It's about students experiencing the true process of learning, and about learning how to learn. Believe me, many groups had to (grumpily and with much eye-rolling and dramatic sighs at yours truly) back up and redo their measurements several times because their graph didn't make any sense at the end. (A lot had themselves moving backwards in time or back to their starting point when they really hadn't gone back there. But if they hadn't actually been the graph, they wouldn't have had their "this isn't right" spidey-senses tingling. When doing a problem on a worksheet, they have no frame of reference for realizing what they have produced isn't right.) Failure was built in to this activity, but it was essential that they experience that--because failure, a little struggling, and fixing are so crucial to the learning process. The payoff is worth it, however. Check out what a few of my students had to say to me during and after the activity: "Mrs. E, I thought this was going to be easy at first. Now I realize I didn't really get this at all."

"I was mad that you didn't just give us notes on this. But now I see that if you had done that, we wouldn't really understand."

"Mrs. E, you're such a jerk." (This is a term of endearment in our classroom. I am a jerk--a jerk for learning.)

I can't do the learning for them, but I can design activities so they can do the learning and experience real learning. I'm not a master at it yet by any means, but I know that doing these types of activities are usually better than any worksheet I can give them.