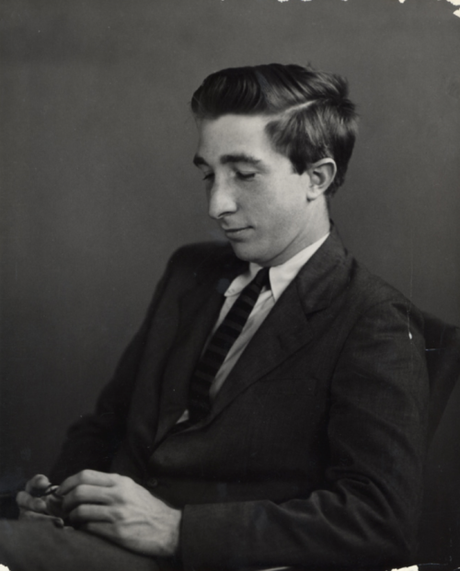

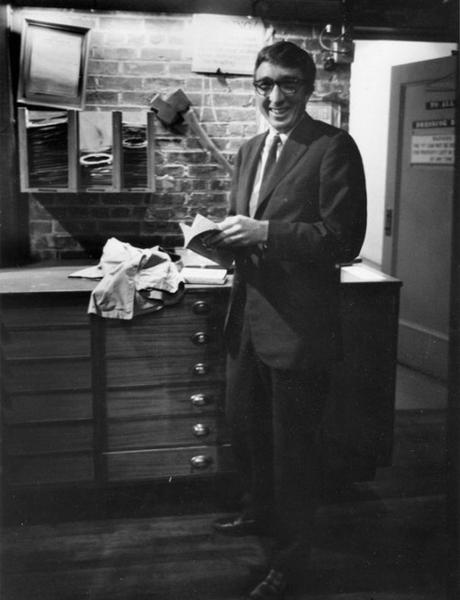

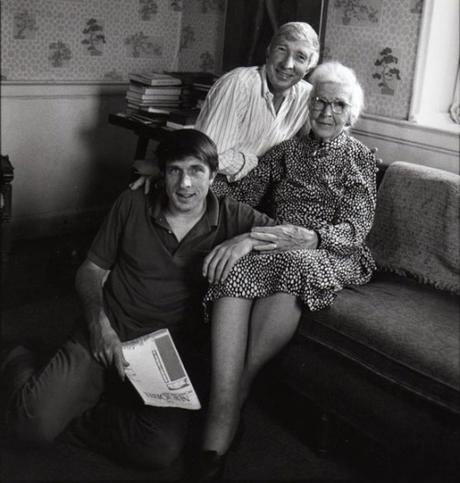

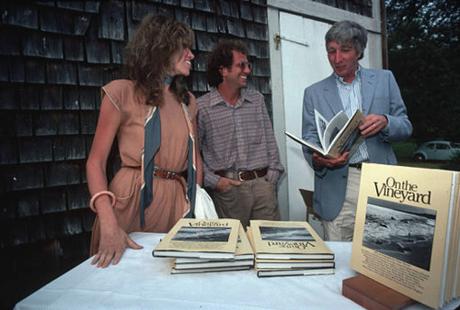

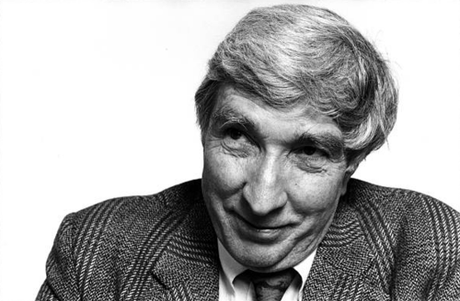

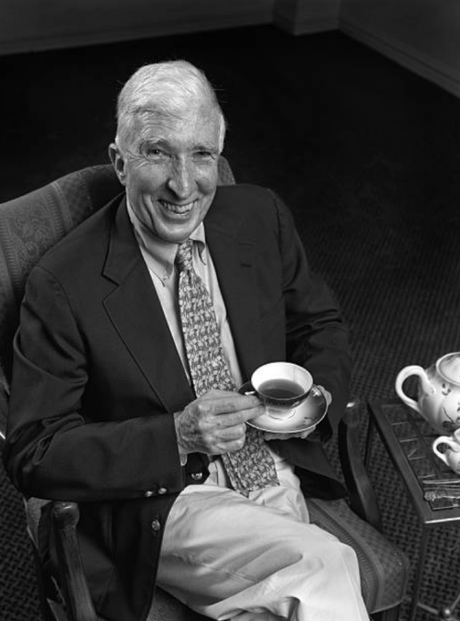

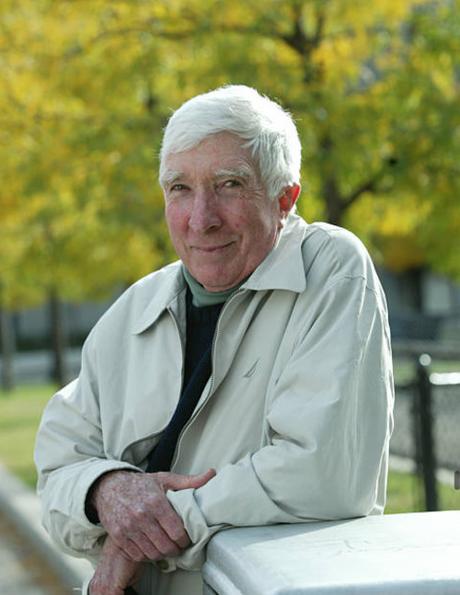

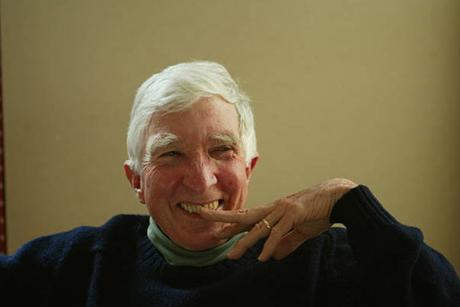

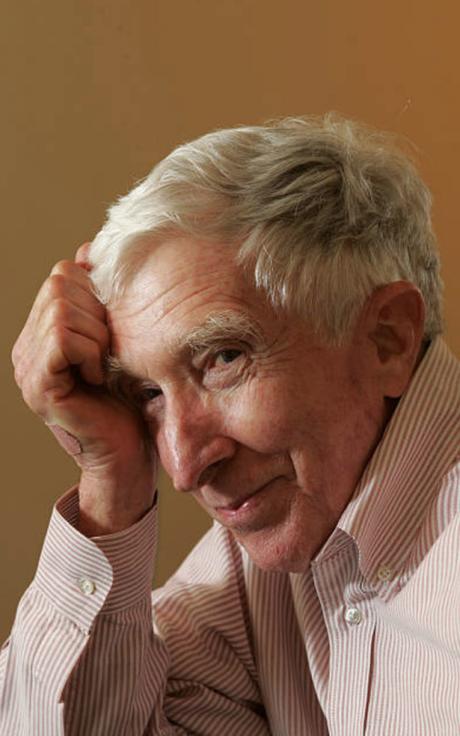

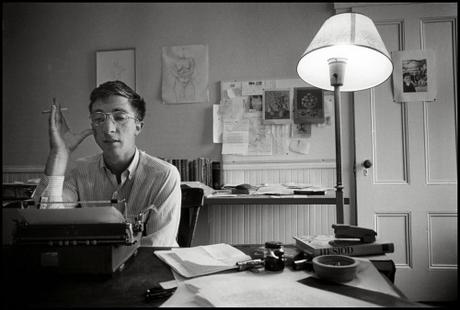

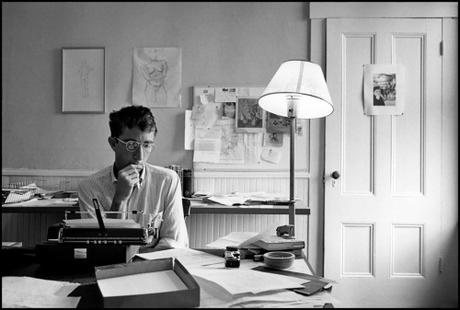

At the time of his death in 2009, John Updike left behind an incredible body of literary work, which included thirty novels, nine volumes of poetry, and an endless number of children’s stories and New Yorker articles. He was not only one of the best writers of the 20th century, but also one of the most prolific. Whereas most writers produce one big book and then brood in silence for five years, Updike charged forward with confidence, producing a new book every year. David Foster Wallace, who was a fan of the writer, once listed some amazing “actual-trust-me quotations” he’s heard from the Updike’s critics. One included the rhetorical question, “Has the son of a bitch ever had one unpublished thought?” Presumably not if he could help it.

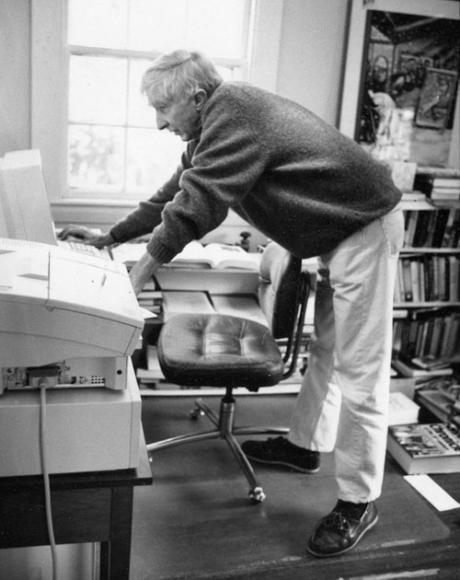

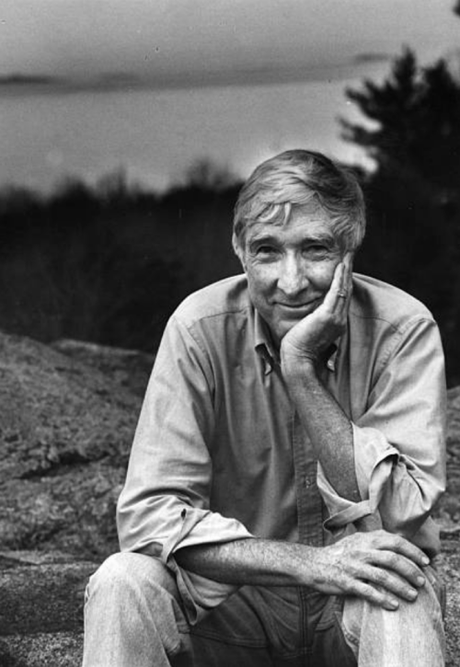

Updike wasn’t just a word processor, however. He was a chronicler of middle-class American life, including those nuclear households with happy children, humming appliances, and a golden retriever. He sought to do with small town, middle-class American families what Jane Austen had done with the landed gentry and Henry James with American expats. He biopsied minute samples of their lives so that he could reproduce them in his books. In his memoir Self-Consciousness, Updike wrote:

My success was based, I felt, on a certain calculated modesty, on my cultivated fondness for exploring corners — the space beneath the Shillington dining table, where the nap of the rug was still thick; the back stairs, where the vacuum cleaner and rubber galoshes lived; the cave the wicker armchairs made when turned upside down against the rain on a porch. I had left heavily trafficked literary turfs to others and stayed in my corner of New England to give its domestic news.

If this sounds incredibly banal, it’s because it was intentionally written to be so. Updike, in some ways, was the anti-anti-modernist. He was responding to a generation of writers that rejected middle-class life and 1950s narratives as a matter of doctrine. Updike stood opposed to men such as George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut, John Cheever, Norman Mailer, and Thomas Pynchon – men who saw the world as heading towards some bleak future. Updike was realistic in his view of suburban life, but wasn’t cynical or grim. “America is a vast conspiracy to make you happy” is his often-quoted line.

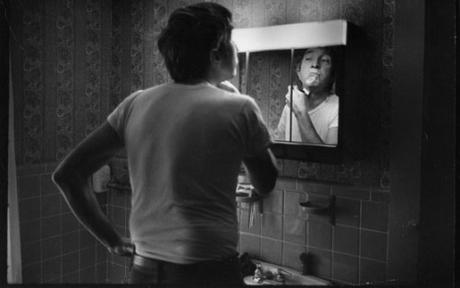

You can get a sense of this in his most famous novel, Rabbit, Run, which was published in 1960, just three years after Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. The novel centers on Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom, Updike’s suburban everyman and “an older and less articulate Holden Caulfield.” A former high-school basketball star, Rabbit feels trapped by his loveless marriage, dead-end job of no great charm, and glorious past as an athletic hero. So, one day, he takes off on a road trip, going south in hopes of finding paradise.

Updike’s cruel joke in the end, however, is that Rabbit can’t run. He sends his protagonist through Cheever country – that part of white America filled with affluent homes, but also similarly stunted aspirations and spiritual anomie. And along his picaresque journey, Rabbit gets lost and frustrated. At some point, he receives some advice at a gas station that basically sums up the book: “The only way to get somewhere, you know, is to figure out where you’re going before you go there.” Rabbit realizes that he can’t drift like this forever, so he turns around and goes home.

Compare this story to writers from the Beat Generation, who saw the road as a real escape from material consumerism and standard narrative values. Their protagonists never returned home – they forged on, finding new and exciting adventures, discovering truths about the human condition, and perhaps had some sex along the way. These characters lived life against a backdrop of poetry, improvisational jazz, and heavy drug use. They broke free of the ball-and-chain that is modernism and lived wild, more authentic lives. Or so we’re led to believe.

Rabbit, Run is often seen as Updike’s answer on Kerouac’s On the Road. It’s a more realistic portrayal of what it would mean if any one of us, the non-Kerouacs of the world, were to try to escape from our banal routines. And it’s a sentiment that many of Kerouac’s critics shared. In her review of On the Road for The Atlantic Monthly, Phoebe Lou Adams wrote: “It disappoints because it constantly promises a revelation or a conclusion of real importance and general applicability, and cannot deliver any such conclusion because Dean is more convincing as an eccentric than as a representative of any segment of humanity.”

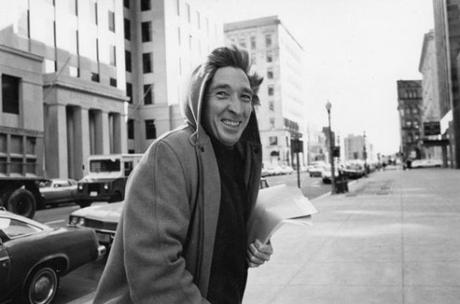

This difference between Updike and Kerouac isn’t just about post-war literature – it extends into fashion. Both authors stayed close to that creative-writing-class imperative to write what you know. Updike lived a quiet, burgherly life in a small, seaside town known for its clams; Kerouac based his book on his real-life road adventures, which he documented in small notebooks. But for everyday men, such as me, Updike is about a closer examination of our realities, whereas Kerouac is about fantasy. On the Road is about living vicariously through Kerouac himself, with the vague idea that maybe one day you’ll break free of the suffocating effects of modernism – except, not really.

And isn’t the act of choosing what to wear every morning similar? There are those parts of closets that feel a bit truer to our authentic selves, and those clothes we wear to escape. In an article last year at First Things, Bruce Boyer wrote:

Clothes have always provided the most obvious indication of both dignity and definition. There was no question in anyone’s mind when Louis XIV walked into the room who was king. His yards of ermine and gold cloth made it easy. But today we see a man walking in midtown Manhattan wearing a pair of jeans, denim shirt and jacket, cowboy hat, and cowboy boots and have no idea what he may be. He may of course be a cowboy, but on 34th Street? All we are given to know is that he wants to be thought a cowboy. At least for today.

I think there’s room in a closet for both, just as I think a bookshelf can hold both Rabbit, Run and On the Road. My own wardrobe has a bit of classical tailoring hanging alongside a hodgepodge of casualwear that ranges from contemporary minimalism to Japanese workwear. Sometimes you feel like wearing an oversized Chimala chore coat with Kapital side zip boots; sometimes you want to wear an all-black outfit with a Margiela five-zip and C.O.F. slim-fit jeans. Clothes can be about dressing up in the fantasy sense.

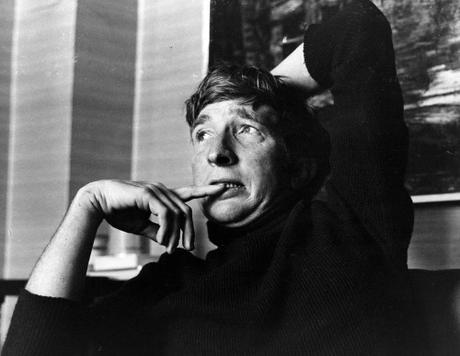

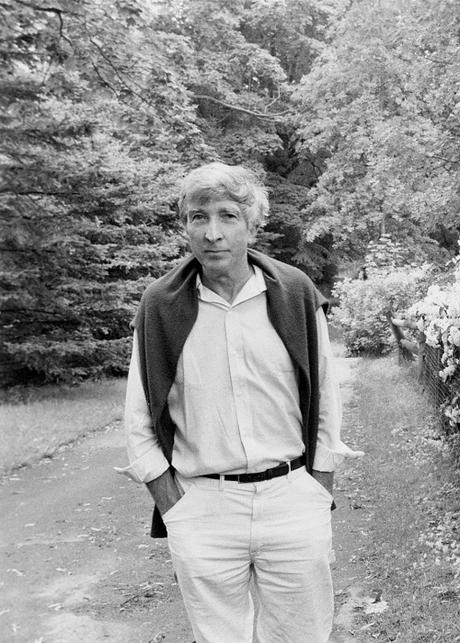

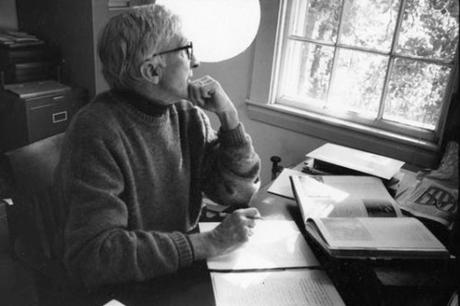

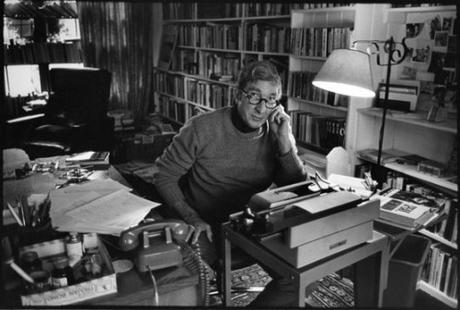

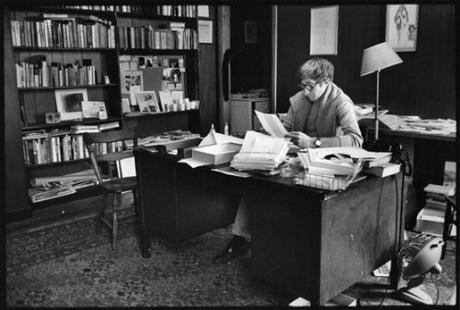

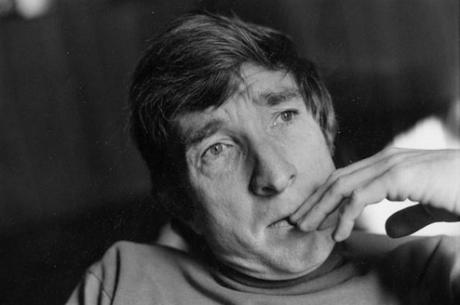

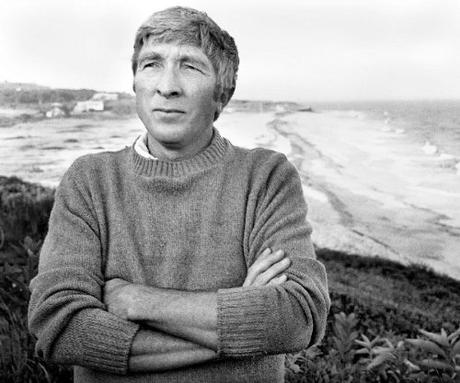

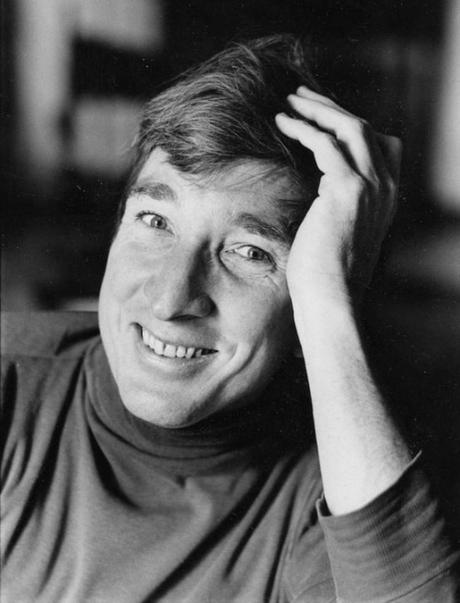

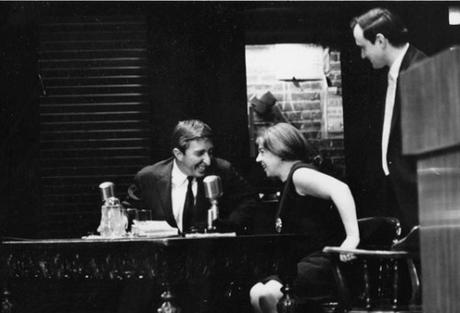

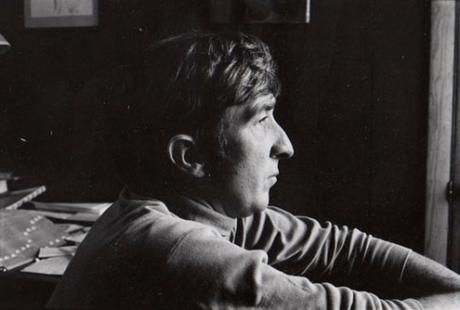

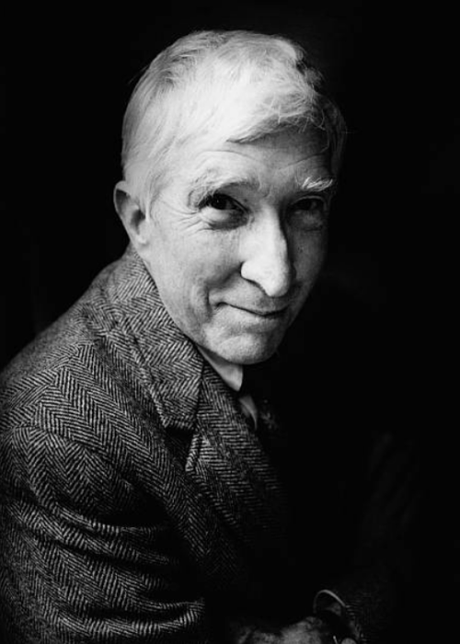

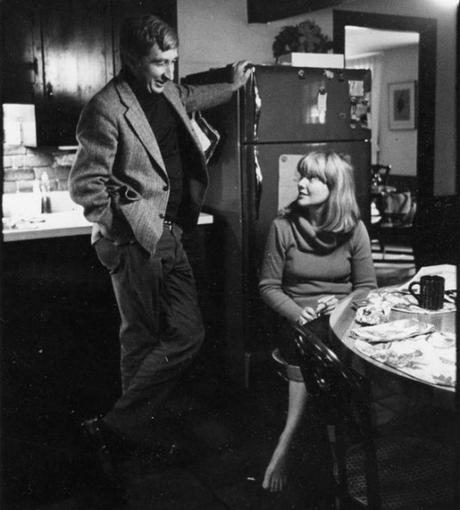

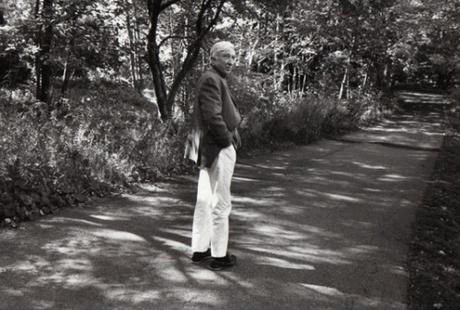

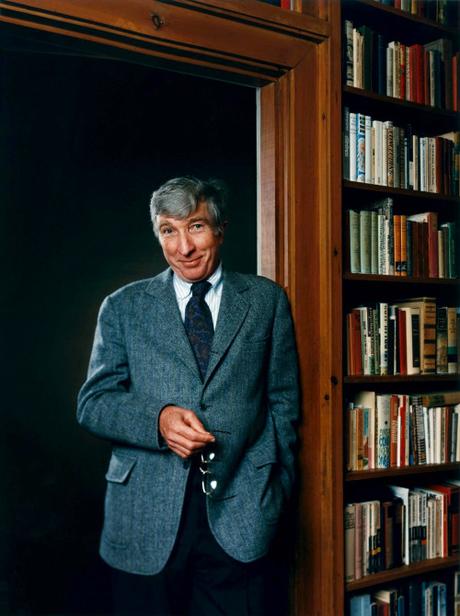

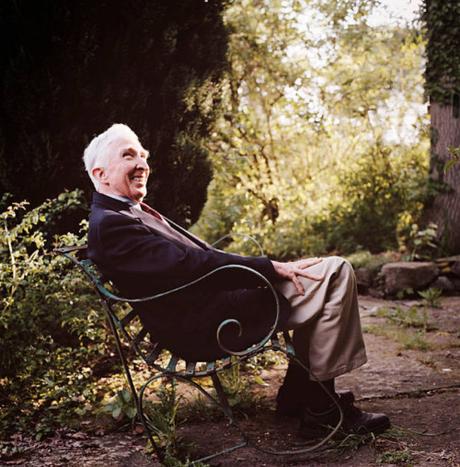

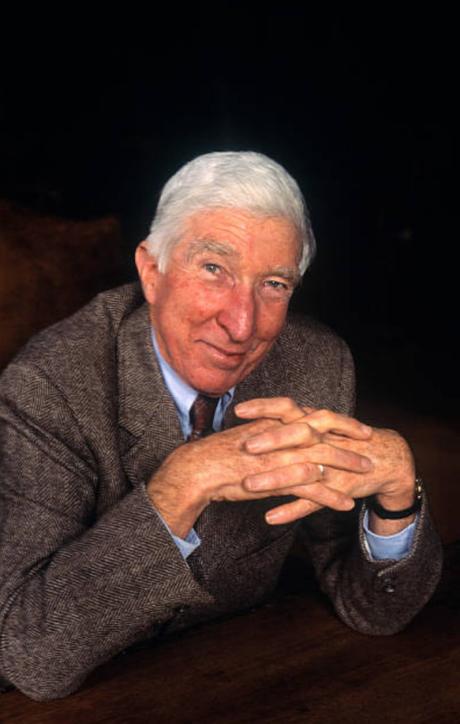

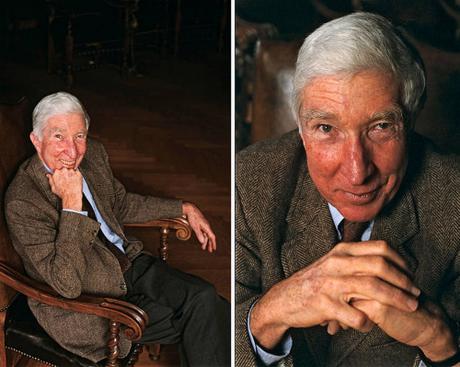

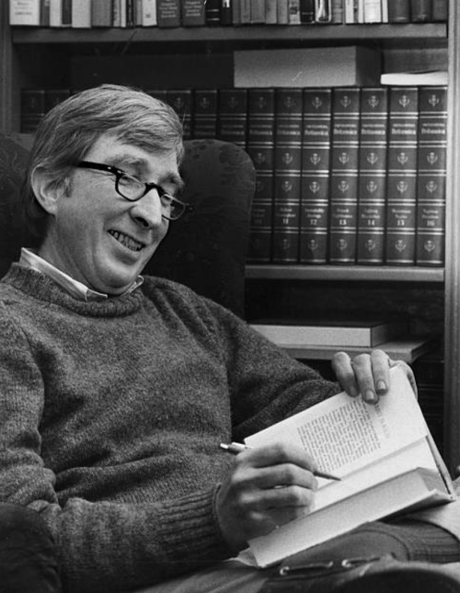

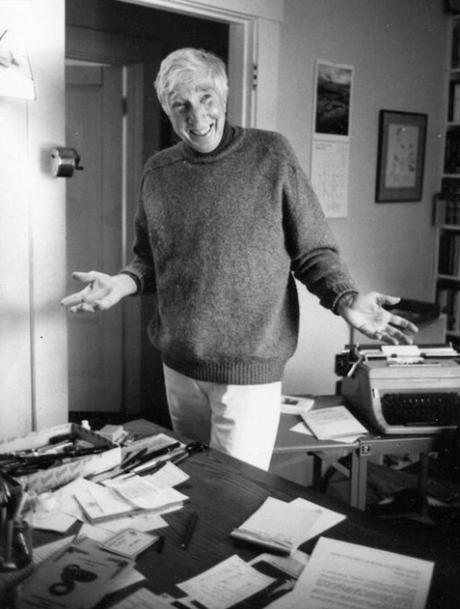

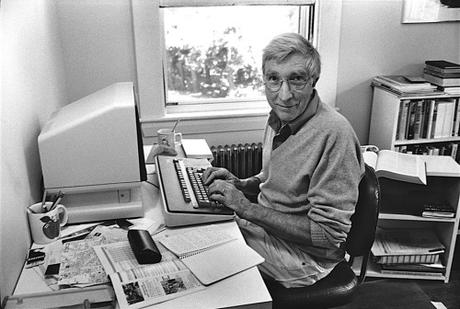

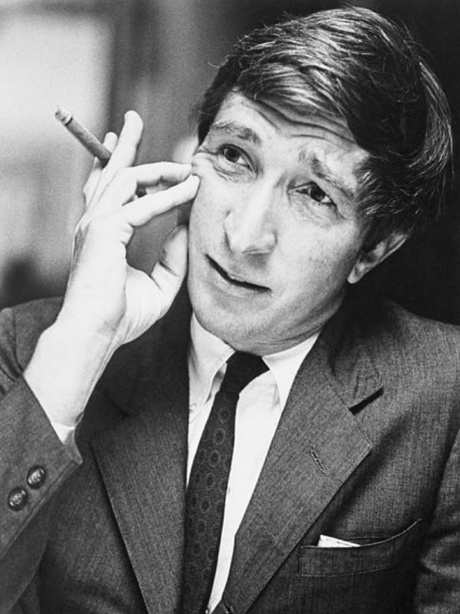

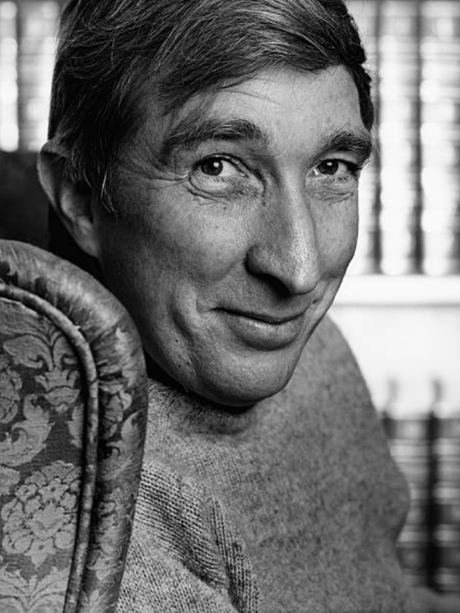

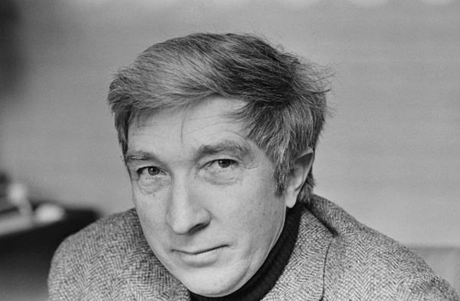

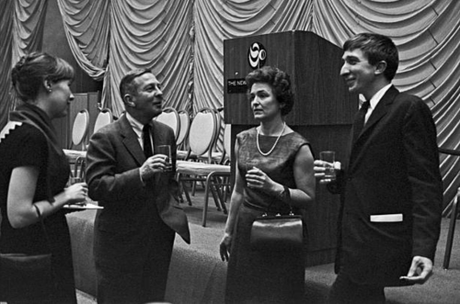

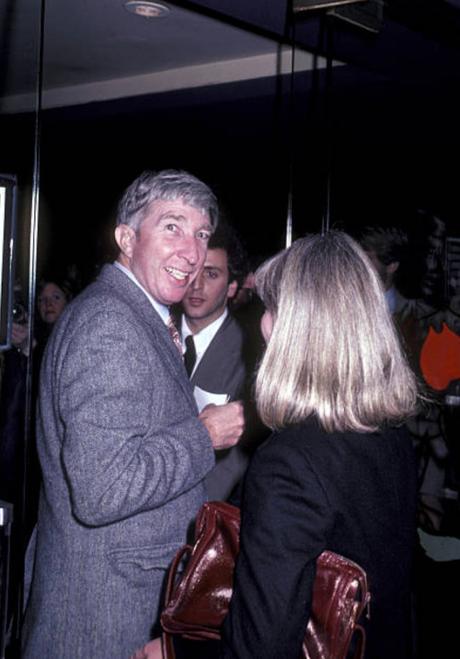

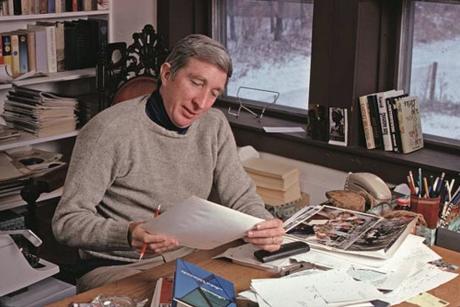

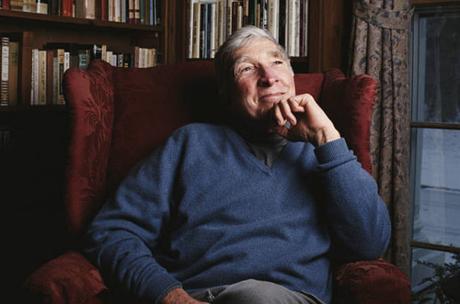

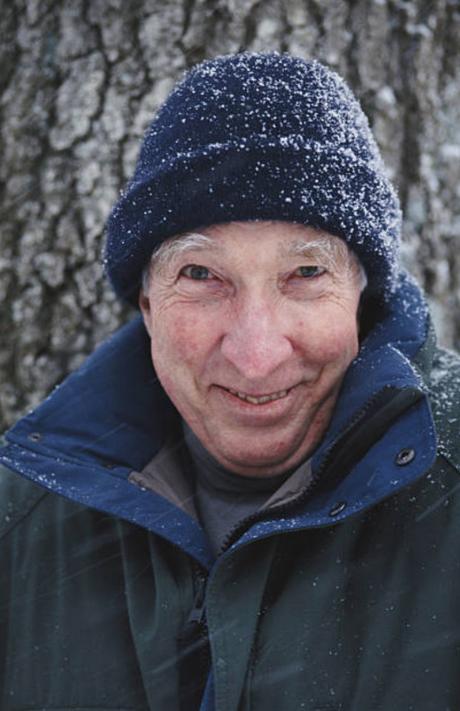

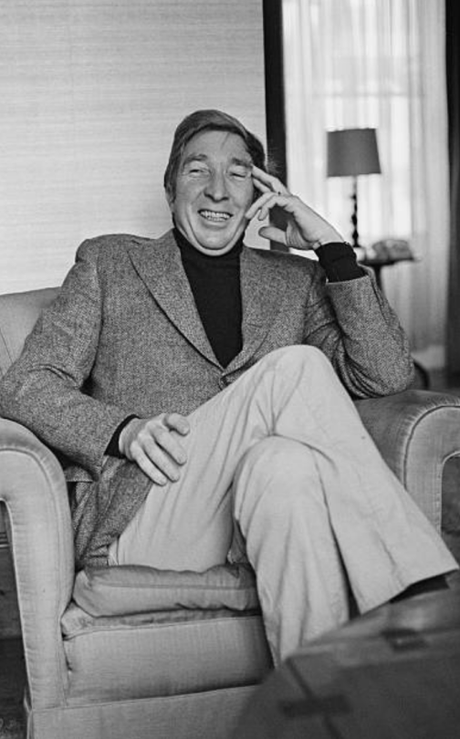

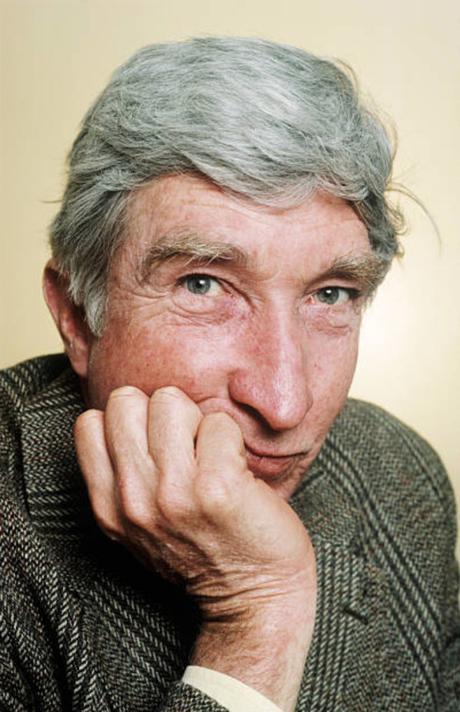

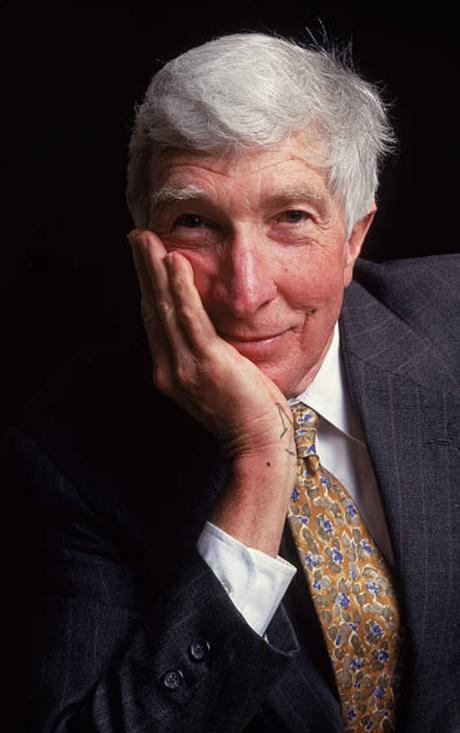

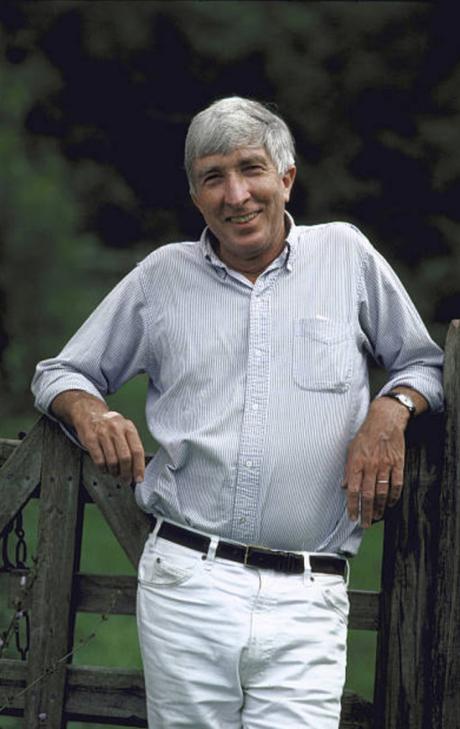

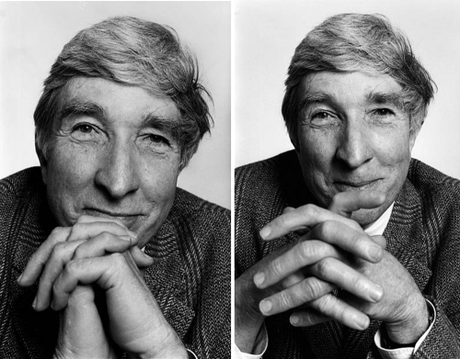

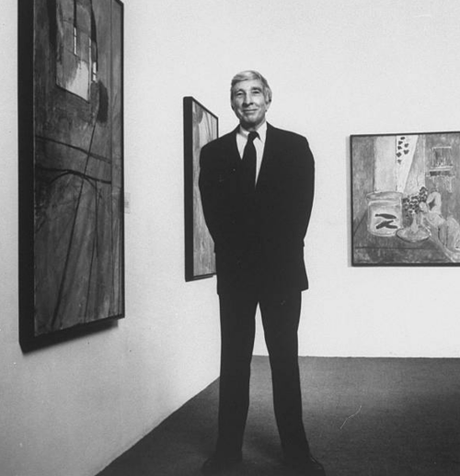

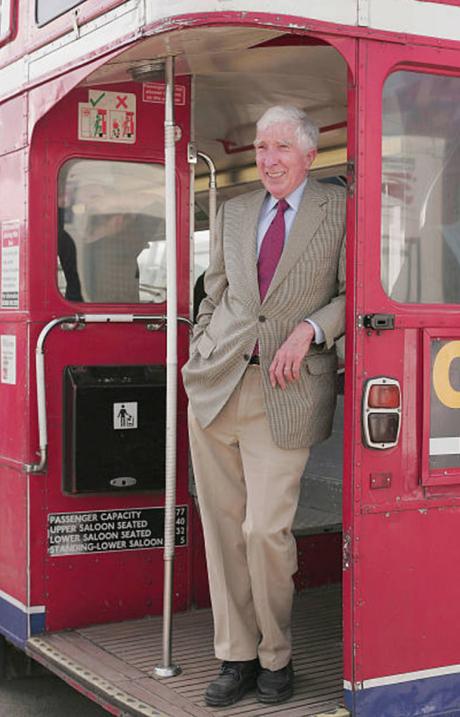

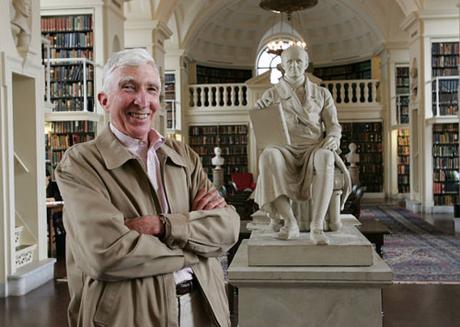

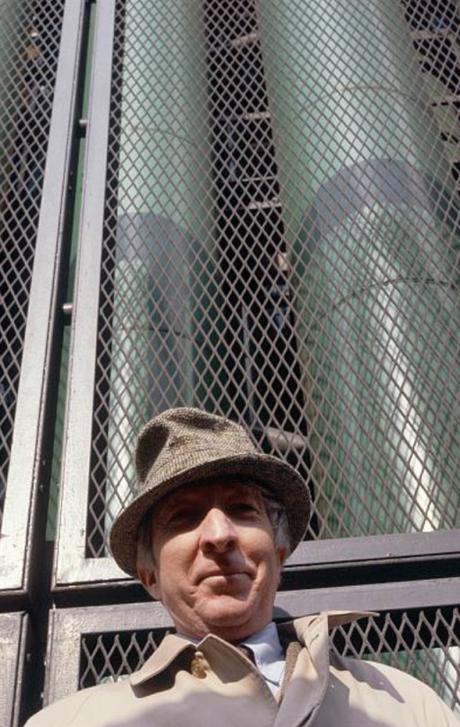

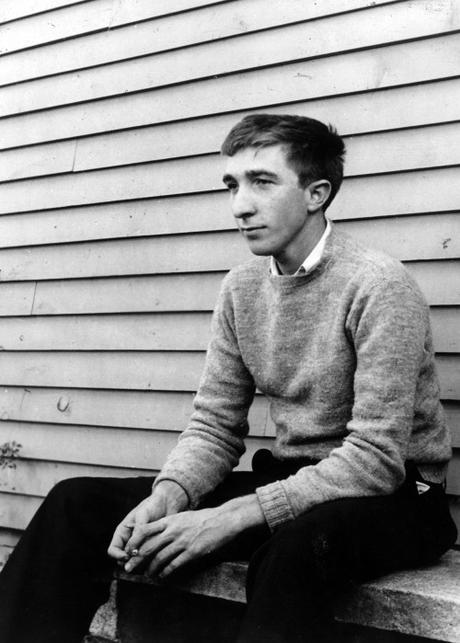

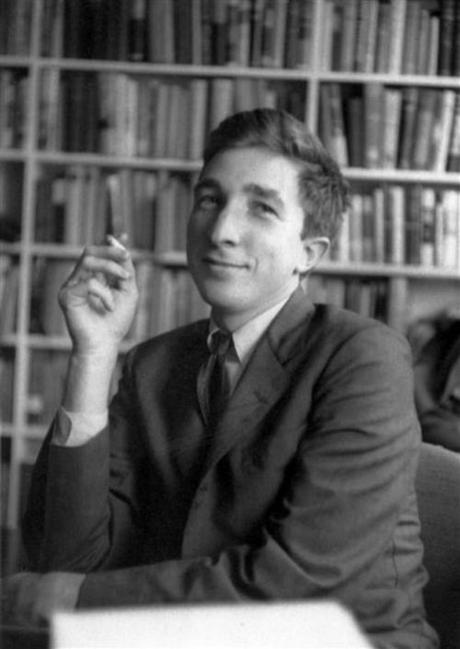

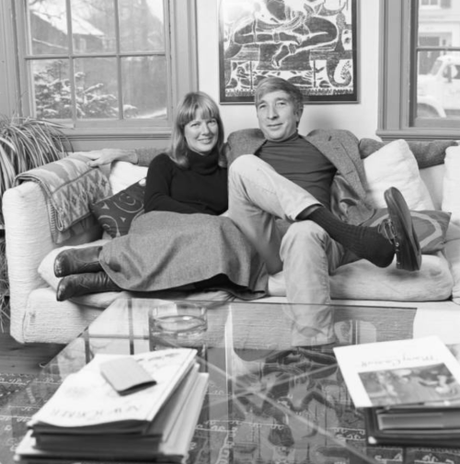

But as a deeply boring and middle-class person, there’s also something comforting about clothes that feel more intimately familiar. That will mean different things to different people, but for me, it’s a wardrobe not too dissimilar from Updike’s. He liked traditional American clothing, but wasn’t priggish about it (his college classmates remembered him as amusingly un-preppie). He favored simple colors such as chocolate browns, deep blues, and off-whites. He wore sport coats instead of suits, slip-on shoes instead of lace-ups, and five-pocket cords instead of wool trousers. He often layered his turtlenecks underneath crewneck Shetland sweaters (an affectation I would not copy, but admire). Updike’s style is distinguished from others in that he rarely wore anything flashy – more a camp-moc man than horse bits. But he looked damn good.

For Updike’s look, you could pick up a dozen button-down shirts from Michael Spencer (a sponsor on this site), Proper Cloth, Brooks Brothers, Kamakura, or Lands’ End. Then one or two soft-shouldered tweeds; a Grenfell raincoat; and some soft-soled moccasins for ambling at home (Oak Street Bootmakers, Quoddy, and Rancourt’s hard-bottom mocs are good if you want something you can wear outside – better still are Alden’s leisure handsewns in shell cordovan or suede). For pants, tan chinos, white jeans, and five-pocket cords are the most Updike-ish, although I would supplement with grey wool trousers. And while the Massachusetts writer loved his thinly knit merino turtlenecks, I prefer thicker ones. Plain-colored Shetlands and grey cotton sweatshirts, on the other hand, are about as close as you can get to knitwear that’s universally useful.

Updike’s critics frequently accuse him of being a “naïve, plain-vanilla realist, uninterested in the formal experimentation that was going on in the world around him.” The same can probably be said of his wardrobe. There’s something deeply boring and middle class about Updike’s clothes, and like his novels, his style doesn’t have the edginess of Beat Generation writers’. Yet, there’s still something charming about it. And if I were to be honest with myself, something intimately familiar.