What does sociology have to offer when it comes to understanding the political phenomenon of Donald Trump as president? It seems that there are a number of different kinds of questions that sociologists ought to consider (link).

Ideology and culture

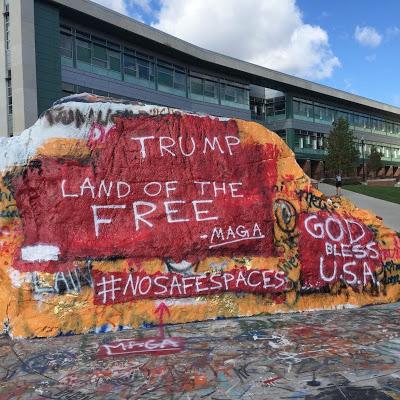

A political movement needs to mobilize a significant population of followers around a set of ideas and values, and a narrative of blame and praise for the current situation (link). There are meaningful themes of communication that help to convey a political movement to the public. There are also pervasive cultural elements that are invoked by a movement -- images, sounds, bits of music and video -- that convey its values in less direct and cognitive ways. It is important to probe those ideological and cultural themes in detail.

As a candidate Donald Trump put forward a hodgepodge of themes and tropes -- birtherism, hateful slanders about immigrants, the need for a strong leader, inflammatory language about race ("What do you have to lose?"), anti-Muslim slurs, and international bellicosity, hostility to "political correctness", and antagonism to women's rights. This really is a dog's breakfast of ideas, failing to add up to a coherent ideology. But as a collection of emotional red flags for various groups of disaffected people, it worked pretty well. And it did appear to succeed in creating a movement of true believers. These true believers are not a majority of American voters, but they appear to be a firmly committed political force.

We need a twenty-first century equivalent to Fritz Stern with his masterful analysis of The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology as an attempt to account for the rise of National Socialism in Weimar Germany (link). Some of that work is being done by scholars who are trying to get to the heart of right-wing populism (link).

Parallels with European populist extreme right parties

There is a high degree of consistency of the Trump rhetoric and ideology, with the xenophobic, anti-immigrant ideology of extreme right parties in various European countries. Even though Trump may seem like a sui generis American extremist, his vision and rhetoric have strong resonance with the extreme right in Europe. Sociologists need to examine the substantial degree of parallel that exists between Trumpism and the far right in Europe. This is work for which comparative historical social scientists are very well prepared. (Here are a few prior discussions of this point; link, link, link.)

It is evident that there is a great deal of similarity across the ideologies of these various extreme-right movements. What accounts for the diffusion and mobilization impact of these kinds of ideologies? Jorg Flecker's collection on the socioeconomic factors influencing right-wing mobilization, Changing Working Life and the Appeal of the Extreme Right (first published in 2007), is a useful resource. Mileti and Plomb provide an excellent review essay, "Addressing the link between socio-economic change and right-wing populism and extremism: A critical review of the European literature". They usefully distinguish between the "conditions of emergence" and the "conditions of success" (quoting Mazzoleni). Significantly, the work described in this volume was written long before Donald Trump was a serious political figure -- suggesting clearly that Trumpism is not a singular American phenomenon.

The mobilization strategies and mechanisms of hate

We cannot underestimate the contagious nature of hate and hateful behavior and speech. Hateful mobilization is powerful and rapid. Better understanding of the mechanisms of social networks, fake news, big lies, and manipulation of belief through right-wing channels like talk radio, Fox News, white supremacist YouTube channels, and targeted FaceBook advertising needs intensive investigation. It is clear today that social media platforms were weaponized by interested political groups, including right-wing extremist organizations, and that these efforts continue. The unwillingness of Facebook to address this problem is indicative of a serious problem of corporate values and corporate responsibility on the part of this multi-billion member social media platform. This failure represents a serious threat to our democracy.

We need to achieve a better and more sophisticated understanding of the mechanisms through which hate spreads in a population, and the means that are deliberately employed by hate-based groups to gain support for their positions (link, link).

The alt-right and white supremacy

A key ideological asset of this oppositional, divisive program for political mobilization is the aggressive propaganda machine of the alt-right. Publications like Breitbart have created a space of legitimacy for racism, anti-Muslim bigotry, anti-Semitism, and white supremacy that is a crucial part of the mobilization of the Trump constituency. And with the appointment of Steve Bannon as chief strategist for newly-elected President Trump, these hateful currents came directly into the White House itself.

International aggressivity

Also essential to Trump's vision is a bellicose, aggressive approach to international relations. He threatens China with naval power, he bullies Mexico, he denigrates Merkel (a key linchpin in a unified Europe), and he speaks carelessly about the use of nuclear weapons. His message of "America first" promises a reckless, bullying approach to international relations that bodes ill for a peaceful future. What role does this bellicosity play? It seems to be a key part of his message to his core constituency: I am strong, I don't care about the rest of the world, I will make them accept my demands. This obviously will fail. But it may lead to reckless use of military force by the logic of Trump's own statements. He has painted himself into a box of bellicosity, at great risk to all of us.

The material causes of a propensity for responding to these messages

Observers right and left have tried to understand the Trump constituency in terms of the "forgotten white lower middle class", with few of the gains of growth of recent decades flowing to these men and women. Shrinking job prospects, hourly wages declining, and other material forces make this group psychologically ripe for anti-establishment, xenophobic, racist, resentful mobilization. Trump panders to this constituency; he will inevitably disappoint them. It is a theme that Justin Gest explores in The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality (link). It is a fair question to ask whether this picture is accurate, or whether the social causes of the rise of extremism lie elsewhere.

Trump's real agenda has proven to be fundamentally at odds with the desires of this group. He has made wild promises, he has denigrated the groups these individuals blame, and he has promised populist and nationalist change. But simultaneously he has appointed a room full of multi-millionaires to his cabinet whose economic interests are patently clear. The economic and tax policies that emanate from the Trump administration are demonstrably ones that favor the one percent. And the first steps the administration undertook concerning health care bore this out. Attacking the Affordable Care Act hurts only lower middle-class people, with the likelihood of eliminating great numbers of people from health insurance and materially shortening their lives.

The inevitable disappointment

So where does our country go when Trumpism fails? One possibility is that the Democratic party in opposition can rebuild its policy platform in a way that realistically works to level the playing field for all Americans. A genuinely progressive plan can create avenues of opportunity that drain a different swamp -- the swamp of resentful, racist neo-fascist groups who brought this strongman to power. But the other possibility exists as well: the resentments and hatreds stoked very deliberately by the Trump political machine have nowhere else to go except into greater extremism. And the politics of hatred, division, and resentment gain even greater support. Cas Mudde's recent The Far Right Today provides a basis for thinking about our future in light of these political currents, and his conclusions are not entirely encouraging.

The far right is here to stay. This even applies to the extreme right, which also survived the repressive aftermath of the 1945 defeat of the fascist movements and regimes that originally inspired it. To be clear, there are few indications that extreme right parties or politicians are returning to political power. Even in Greece, which probably resembles Weimar Germany more than any other democracy, the neo-Nazi XA is remarkably stable at roughly 5–7 percent of the vote. That said, extreme right actors and ideas have recently been praised by two of the most powerful men in the world, Brazilian president Bolsonaro (military dictatorship) and US president Trump (“ alt-right” demonstrators in Charlottesville). Moreover, antisemitism and racism have returned to the center of the political debate, be it more implicitly in traditional media or more explicitly on social media. (The Far Right Today, 174)

...

The ultimate goal of all responses to the far right should be the strengthening of liberal democracy. Put simply, only fighting the far right does not necessarily strengthen liberal democracy, but strengthening liberal democracy will, by definition, weaken the far right. That the two do not always go hand in hand is not always acknowledged. Limiting free speech or the right to demonstrate not only infringes on the democratic rights of far-right activists, it undermines these rights in general, and thereby the liberal democratic regime. This is not even to speak of the tendency for repressive measures aimed at one group to be later applied to other groups, including some that are neither radical nor right. (178)We have our work cut out for us.