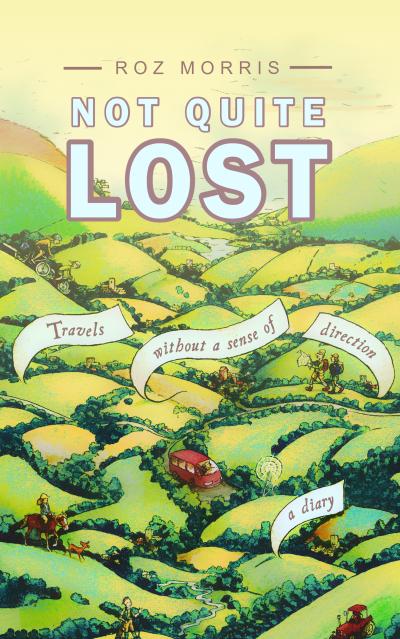

Today I’m pleased to be receiving a visit from one of the most prolific and versatile people I’ve met in the book business, and many of you will know her too: Roz Morris is an award-nominated novelist (My Memories of a Future Life; Lifeform Three), book doctor to award-winning writers (Roald Dahl Funny Prize 2012), has sold 4 million books as a ghostwriter and teaches writing masterclasses for The Guardian. Not Quite Lost: Travels Without A Sense of Direction is her first collection of essays.

Today I’m pleased to be receiving a visit from one of the most prolific and versatile people I’ve met in the book business, and many of you will know her too: Roz Morris is an award-nominated novelist (My Memories of a Future Life; Lifeform Three), book doctor to award-winning writers (Roald Dahl Funny Prize 2012), has sold 4 million books as a ghostwriter and teaches writing masterclasses for The Guardian. Not Quite Lost: Travels Without A Sense of Direction is her first collection of essays.

Roz’s latest creation is hard to pin down, in a good way. Were it not for the multiple settings, it would have made for a good Writers on Location post because place is such an effective catalyst and starting point for each of these accounts in this short book (I keep wanting to say ‘stories’ – the first, in which Roz revisits her childhood home from a distance is positively novelistic.) The accomplished writing sets off her acute observation and gift for harvesting drama and meaning from the strangeness and randomness of the outwardly unexceptional. Intriguing and different – Not Quite Lost is a great find.

There’s a moment in my first novel, My Memories of a Future Life, when the narrator is learning a piece for the piano. She’s dissatisfied with her interpretation, so she plays extremely slowly, to take each phrase into her heart and discover the detail and nuance. Then she plays it at tempo, and the richness she seeks is there.

This detail came from one of the many musicians I interviewed for the novel, and I recognize the same process of discovery when I’m working on a piece of writing.

I particularly felt it this year, when I worked on a book I thought would be swift to complete. I’ve been writing a novel that requires a lot of technical research and I needed a breather, or it needed a breather from me. So I decided to write a palate cleanser – a collection of travel tales, harvested from a diary I kept while on holiday with my husband. A stay in a Napoleonic fort where we endured water torture from its leaking roof, with variably hilarious results. There are also escapades from when I’ve been out of my usual element – like the time when I cheekily took part in an audition as a dancer for an advert, got the job (to my amazement), and then spent two weeks in a Strictly-style bootcamp, expecting all the time to be fired.

But when I rattled these tales into a Word document, some of them didn’t work. I was puzzled. My Strictly adventure had entertained friends in chatty emails and at dinner parties. There were colourful characters, tricks of the trade and ego-bruising mistakes. The leaking tower was also good value in conversation. But on the page they were brash, insubstantial.

So I slowed down, right down. Instead of leaping from laugh to laugh, I looked at every moment. Like the pianist taking her time, listening for nuance and hidden shapes. Resonances coming back from the book’s bigger thematic web. The tower with the leaking roof wasn’t just a holiday mishap. It was a fundamental negotiation of what one partner would put up with for the sake of an adventure with the other – the balancing act of a long relationship.

The dance advert, under the showbiz novelty, was also a deeper challenge. Any fan of Strictly will tell you the experience changes lives. As I bumbled through rehearsals, convinced I would be found out, it became my daily reckoning with imposter syndrome.

Doesn’t this reveal one of the essentials about why we love reading? It is so personal. We feel we are being trusted, as if a stranger has decided to confide in us. The reader isn’t a crowd. It’s one person.

I was probably too young to grasp the full significance of many of the story events. They were about adult practicalities I knew little of. But it didn’t matter. Every paragraph was a joy, simply for the way Maxwell talked. He was entertaining, clever and amused, but he also had other, gentler qualities – he was affectionate, self-deprecating, vulnerable. I read and reread all his books until they were in tatters and then discovered more kindred souls in the school library, companionable writers of great personality – James Herriot, Gerald Durrell, Eric Newby. And more recently, of course, Bill Bryson.

Reading is a curiously one-channel experience. We don’t hear the storyteller’s vocal emphasis, see their expressions or catch the reactions of the other listeners. Nevertheless, it seems like real, living contact. We get the journey mind to mind, as though we are folded into the writer’s inner lands, transposed into their soul. They gift you an experience that has shaped them, and invite you to be shaped by it too.

That’s why a book feels so personal. You feel like it was written just for you.

Thank you to Roz for joining me on the Literary Sofa – there’s so much for booklovers to relate to in this wonderful piece. That feeling of intimacy – a kind of search for connection – between writer and reader is hugely important to me, enabling me to write things which I could never express any other way (I discussed it in this interview with Greenacre Writers, if you’re interested). Most of us will have occasionally felt something was written for you, and those books often find their way into our hands just when we need them. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this, whether you’re a reader, writer or both!

Advertisements