Enrico Caruso (ca. 1910) listening to a gramophone recording

Enrico Caruso (ca. 1910) listening to a gramophone recordingDawn of the Sound Era

In the beginning (of the recording industry, that is), there were wax cylinders. The tinny sound that came out of those cylinders was one reason for their demise. And because of their fragility, longevity was not a strong point, either.

They were eventually supplanted by longer-lasting yet heavier to carry 10-inch platters. That’s when thick, circular discs could be played at an astounding 78 revolutions per minute, mostly by hand-cranking a lever that would make rudimentary turntables revolve at approximately that speed.

A needle or stylus was lowered onto the turntable via an antiquated “tone arm.” This device would then cut into the record’s grooves. The vibrations from the grooves to the stylus were transmitted to a large acoustic horn, which emitted the sound of what was preserved on those same grooves that could then be heard in a record shop, or one’s living room (known as the parlor).

Variations in the makeup and performance of these elemental record players (called gramophones) resulted in widely fluctuating pitches. This undoubtedly effected the enjoyment of an artist of Caruso’s renown as he flung forth his trademark “Vesti la giubba.” Uh, was that A sharp or A flat we just heard? Be that as it may, those fortunate enough to have afforded this revolutionary equipment could indulge themselves to the fullest in the evolving pastime of record listening.

It was said at the dawn of this new era of sound that Puccini’s arias were made to order for the gramophone (later dubbed the phonograph) — an obvious reference to their brevity and a boon to those enamored of his oeuvre. On the other hand, anything by Wagner, whose main quality was his persistent long-windedness, was clearly unplayable in this form.

This highlighted one of the major defects of the 78-rpm record, i.e., its short playing time. At three to four minutes per one-sided disc (depending on a turntable’s speed and accuracy, as well as the record’s groove spacing), this was hardly enough time for the prelude to Lohengrin. When 12-inch platters came about, the time-span increased to just over five minutes per side, give or take a few. You can imagine how many platters it would take to hear a relatively brief work such as Mascagni’s 80-minute Cavalleria Rusticana, let alone something of Der Rosenkavalier’s length.

Soon, cumbersome 78’s were replaced by longer lasting 45-rpm’s, to be replaced later still by the LP sometime in the late 1940s. Around the mid-1950s, the 45 had been relegated to such genres as folk, pop, blues, jazz and rockabilly, music that barely lasted a full three or four minutes per side.

With further technical refinements and the development of the 33 1/3 long-playing album, as much as a half hour of time on either side (again, depending on the microgrooves in between) could be taken up with vocal, instrumental, orchestral and/or choral programming of varying types and degrees. Hah, Götterdämmerung be damned!

Thus the notion of the complete opera album came into existence, with “complete” being a relative term — not that opera wasn’t available on those old 78’s, not by a long shot!

Surprisingly, a goodly amount of the standard repertory had already been committed to disc by the 1930s and 40s, the so-called Depression and War years. The downside, as stated earlier, was the sheer size and bulk of those albums. In many cases, a work such as Verdi’s Aida would require a huge financial outlay (for the time, of course). Not to be done in by the cost factor, the weight of having to lug around 30 or more platters was off-putting, to put it mildly.

Along with the above problems, most opera sets were severely cut in order to fit what remained of the music onto those hulking discs. Added to which, the vintage sound quality of those early acoustics and the slightly more tolerable electrics were hardly what I would call state of the art.

Indeed, the 33 1/3 LP record had come along at precisely the right time.

Opera as Spectator Sport

Even better for opera buffs, the next series of tweaks and innovations — the development of stereophonic sound reproduction with that of the opera album itself, which included deluxe librettos, copious liner notes, and historical and biographical information — became a godsend to novice listeners such as myself.

For the first time one could hear an uninterrupted presentation of Wagner’s Ring cycle, or stretch one’s comfort zone immeasurably by taking a chance with those interminable Strauss monstrosities. The other novelties that stereo reproduction introduced us to were the enhancement of and appreciation for opera as a performing art.

Still unsatisfied, avid collectors the world over would scour their local record shops for ever more out-of-the-way anomalies, on what knowledgeable aficionados might call “privately issued” labels. Others less inclined to political correctness would prefer to use the term “pirated editions” of their favorite artists or operas. Such rarities as Catalani’s Loreley, Zandonai’s Francesca da Rimini, or the Lisbon Traviata, for example, were at one time considered the Holy Grail for lovers of the form.

Opera fans my age or older would search high and low and over a vast range of pre-recorded formats, either on reel-to-reel tape or low quality discs, for that one performance, or that one outstanding moment, that towered above the rest — many preserved, unfortunately, in positively excruciating sound.

Still, what price wouldn’t fanatics pay to be able to relive Maria Callas’ spontaneous high C from Mexico City in the conclusion to the Triumphal Scene from Aida, or tenor Franco Corelli’s gasp-inducing, stratospheric assumption of Calàf to soprano Birgit Nilsson’s icy Princess Turandot? How about Mario Filippeschi’s dramatically declaimed Radames from the Naples Opera? Did he really take that phrase, “Sacerdote, io resto a te!” all in one incredible breath? You bet he did! Opera was treated as a spectator sport in days gone by….

Moments such as these were unheard of when complete opera albums appeared on the scene. What was so often heard in the opera house could not hope to be captured or duplicated in the studio — nor would it. The point of record albums was to introduce prospective buyers, both neophytes and veterans alike, to the joys of listening to a given work in the comfort of one’s abode, just like in the old days of grandpa’s gramophone. There, one might begin to cultivate an intimate relationship with opera, one that would nurse you through the difficult times.

Today, we have YouTube, live streaming and other Web-based methods of revisiting those fabulous moments from the past. Back in the LP era, though, you were limited not so much by the medium of the analog recording itself as to the content the record companies put out into the marketplace. For therein lies the rub: economics and the reality of the complete opera recording business.

As they approached the end of the millennium, the classical divisions of the most highly respected record labels of the 1950s through the late 1980s (RCA Victor, Decca/London, EMI/Angel, Deutsche Grammophon, Philips, etc.) experienced shrunken budgets and cost-cutting measures on an ever-widening scale. It was an accepted fact that, over the span of many decades and with the exclusion of artistic merit, complete opera albums were considered a money-losing proposition.

Given the cost of having to pay for 100-piece orchestras, for 60 or more choristers, for conductors of unquestioned repute, and for singers of superior abilities, to include sound engineers, recording technicians and other highly skilled professionals, the size and scope of such an endeavor as recording a complete opera remained prohibitively expensive.

When record companies started recording their efforts at, say, La Scala, Milan, or inside the Rome Opera House, as many of them did early on in the process, the costs were shared by most participants. Frequently, budgets were kept in check or out of the equation entirely over the objections of those in charge of the enterprise. “Never mind the bottom line,” some record executives would insist, “it’s the preservation of the art form we care about most.”

As salaries skyrocketed and the tremendous physical and financial demands of traveling overseas increased exponentially, the break-even point for producing and releasing complete opera albums had long-ago vanished.

Nowadays, with most of the standard and not-so-standard repertory items already firmly “in the can,” what was there left to record apropos of the opera?

My Time with My Favorite Pastime

Recalling my own adventures with the recorded art, I can tell you that everything I learned about opera first started with my listening to it. And what was it I listened to? Why, the radio, of course! Where else could a kid from the inner city enjoy opera at his leisure — and for free?

In my early teens, I couldn’t afford to attend live performances, not until I started working. Oh, there were plenty of live options: the Metropolitan Opera, New York City Opera, Carnegie Hall, Town Hall, City Centre, and Lincoln Center. All were available, but not to me.

No, I grew up listening to the Met on the radio, as many people my age did. Fortunately, I discovered a wealth of opportunity at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. There, I could borrow complete opera albums to my heart’s content. Prior to that, I had spent many a free hour at our local branches, pouring over books and librettos of my favorite works, and jotting down the words to my favorite arias, in between studying for exams and such.

The unalloyed pleasure of listening to a complete opera, unencumbered by daily chores or current events, is something I will always treasure with fondness, longing and a large measure of nostalgia. Those were the times I could really sink my teeth into dissecting the content of what the performers were trying to achieve when they sang their roles in a foreign tongue. Having the original Italian, French, German or Russian libretto at hand, while following along with an accompanying English translation of the text, opened up a marvelous new world of knowledge and comprehension.

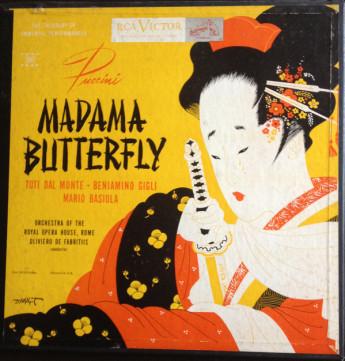

More significantly were the influences on me of such classic albums as the Georg Solti-conducted Ring cycle on Decca/London and the RCA Victor Madama Butterfly with Gigli and Dal Monte, real eye-openers as far as my acquaintance with the medium was concerned. I would also add the RCA Victor Aida with Milanov, Bjoerling, Barbieri, Warren and Christoff, along with the Decca/London Fanciulla del West with Tebaldi, Del Monaco and MacNeil, as testaments to their staying power.

My self-studies began in earnest with the earliest of the items indicated above, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Originally released on 78-rpm records in 1939, this RCA reissue introduced me to my parents’ favorite work, one they had heard often in Brazil, in particular on the night before my birth (for a more detailed description of this event, please see the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/opera/). These old monophonic LP’s had been played so often that the staccato fugue introduction was by now unlistenable, so scratched were the sounds that emanated from their grooves.

Beniamino Gigli, the Pinkerton, was in his element. The lieutenant’s caddish nature, the good humor he exhibited in his exchanges with Goro and Sharpless, and the ardent deference paid to his teenage bride Cio-Cio-San, were well preserved, to which can be noted the pouting, sighing tones Gigli was famous for. No other tenor on records has captured that quizzical aspect of the line, “Milk punch o whisky?” when offering the American Consul some refreshment. I always wondered, as many listeners no doubt have, what the hell “milk punch” was? My best estimate would be the Italian librettists’ erroneous translation of Japanese saké.

Toti Dal Monte, an acknowledged coloratura at the time the recording was made, was a controversial choice for the title role. Her voice was thin and high-pitched and may strike listeners’ ears as irritating. However, she alone (among a surfeit of recorded Butterfly interpreters) immediately convinces us of the “little girl” behind the arranged marriage to the foreign naval officer. Because we know she was only a child-bride, her rapid transformation into adulthood is all the more striking for its fierce determination. With tears flowing and an astounding ability to act with the voice, Dal Monte’s ritual suicide is the most heart-breaking on record, and the most emotionally wrought. It takes a steady hand not to be overcome by the sheer intensity of her performance.

The thing I noticed most, though, as I followed along with the libretto, was where the text diverted from what was actually recorded. I wasn’t aware of this at the time, but RCA Victor had inadvertently printed the ORIGINAL 1904 libretto to the opera, not the thoroughly revised 1907 Paris edition of Butterfly — the one most opera-goers are familiar with and which the world’s opera houses have continuously staged. How odd, then, and how confusing for a neophyte such as myself! But instead of frustration, curiosity got the better of me. I needed to learn WHY there was a difference between what Gigli was singing and why a large portion of his dialog was missing from said recording.

Years later, when I became aware of the multiple versions of Puccini’s opera, I realized the Butterfly we’ve seen on stage was not what the composer had intended. I sought out and bought a CD that included what was available of the original source material, along with the various modifications introduced at Brescia not four months after the work’s disastrous premiere at La Scala, as well as further snips and cuts.

The result was a more refined reworking of the composer’s conception, one that centered primarily on the character of Cio-Cio-San, as the above recording certainly does, and on her growing maturity, both personal and psychological, as a mother and as a woman, which Dal Monte superbly encapsulated.

All this from a sonically compromised, monophonic recording.

(End of Part One … To be continued)

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements