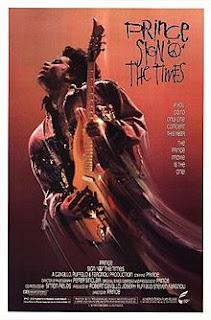

Like Purple Rain, the film of Sign 'O' the Times matches the album it supports. The former visualizes the artist in ascendancy, matching the jubilant, youthful bravado of songs like "Let's Go Crazy" and, of course, "Baby I'm a Star." Its narrative progression is basic but executed with sufficient weirdness to allow for idiosyncrasy and the odd bit of emotional resonance (the belabored journey of the title song within the film, to say nothing of the track itself). And like the album to which it is linked, Purple Rain is at once dated and outside time, a relic of outlandish '80s pop culture and a refinement of that culture into an enduring piece of art.

Like Purple Rain, the film of Sign 'O' the Times matches the album it supports. The former visualizes the artist in ascendancy, matching the jubilant, youthful bravado of songs like "Let's Go Crazy" and, of course, "Baby I'm a Star." Its narrative progression is basic but executed with sufficient weirdness to allow for idiosyncrasy and the odd bit of emotional resonance (the belabored journey of the title song within the film, to say nothing of the track itself). And like the album to which it is linked, Purple Rain is at once dated and outside time, a relic of outlandish '80s pop culture and a refinement of that culture into an enduring piece of art.Sign 'O' the Times has almost nothing in common with Albert Magnoli's film, but then Sign 'O' the Times the album so scarcely resembles the music of Purple Rain. Like the double LP, Sign 'O' the Times begins with what appears to be a story, the theatrical staging of the movie analogous to the lyrical collection of headlines that is the album's opening title track. But then, as quickly as a story emerges, it dissipates, giving way to a pure rush of eclectic songwriting and performance that shows off the best pop star of his time at the top of his talent. From the overbearing stage design to the colliding moods of the 13 songs chosen for the final cut, Sign 'O' the Times matches the unwieldiness of Prince's cobbled-together album (these two haphazard vinyl discs themselves the result of whittling down three separate abortive projects, two of them multi-LP themselves, into one release). Yet it also matches the music's sense of unexpected cohesion and its uncontainable skill and force. There are better directed concert films, and ones that feel more definitive, but no other live document so immaculately captures the filth and fantasy of rock's id.

The stage onto which Prince rolls out his housequake serves as a receptacle for the 20th century's seedy underbelly. Its flashing neon signs, mock-up high rises and chain-link fences combine a 1930s/40s film noir aesthetic of urban underworlds with a contemporary layer of drug crime and porn. Bathe the whole thing in smoke that looks as if it rose carrying stink and disease from manhole covers and you get a set that looks as if it sprung from the nightmares of the buttoned-down, socially conservative forces who went apoplectic with sexual shock when Prince released "Darling Nikki." In his own review of the film, Robert Christgau brought up the sharp contrast of this cluttered, grimy setup to the minimalist, clean staging of the Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense. That movie deservedly has a reputation for being perhaps the greatest concert document of them all, but it is hard to argue with Christgau and co-writer Carola Dibbell that Prince's body-fluid-crusted grease pit feels more aligned with the spirit of rock than the arty chiaroscuro that frame David Bryne and co.

What links the two artists and movies, however, is the sense of sheer delight in the party atmosphere of the music. The Heads of 1984 and Prince of 1987 could even be traced back to mirror reflections of each other: Talking Heads the group of art-school students who made angular post-punk before growing outward into the unlikeliest of funk acts, Prince the disciple of Sly & the Family Stone and James Brown who grew into pop's most prominent and aloof auteur. And just as a whole assembly of musicians and dancers joined the original quartet of Talking Heads members to transform their austere anti-pop into a jam, so too does Prince, fresh from firing the Revolution, combat his own musical insularity with a gang of backup players, dancers, even a horn section to literally jazz up some arrangements.

But if Talking Heads were tight and well-rehearsed, Prince's lineup was tighter and downright regimented. They blister through sharp pop like "Sign 'O' the Times" and "Play in the Sunshine" while letting the groove stretch until just before the breaking point on jams like "Housequake" and "It's Gonna Be a Beautiful Night." Prince finds the balance between incessantly rehearsed perfectionism and spontaneity, both in the music and the dancing. As his backups (a blend of men and women headed by a forcefully exuberant little spitfire named Cat) hit their marks with honed precision, Prince sometimes dances in step with them and sometimes thrashes around in a way that trades his balletic grace for sheer hoofin' passion. The addition of horns, a precursor for Prince's later live shows and recording lineups, manages to show off his gift for (re-)arrangement that also offers a simultaneous look forward and backward, musically speaking. The hot jazz brought by the horn section meshes surprisingly well with the hyper-processed, fat-bottomed electronica of Sign's solipsistic construction, its aural hat tip to the roots of raunchy, racial, radical 20th century popular music also the first of Prince's many on-the-nose but welcome reminders that jazz is no longer "pop" only because the vague "they" say it's not.

Furthermore, the jazz instrumentation modifies Prince's status as a bandleader at a crucial point. Prince was coming off the acrimonious dissolution of the Revolution just as Wendy & Lisa were establishing a significant input into the group's creative process, marking a return of the one-mand-band aesthetic as heard on early gems like Dirty Mind. By employing so many new players that one wonders how anyone even has space to dance on stage, Prince could still exert authoritarian control while focusing those control issues onto just the music rather than the tedious behind-the-scenes politics that drives wedges between friends. Yet the most striking aspect of the concert is the amount of screen time Prince cedes to the others. This is true not only of established collaborators like Sheila E (who gets more than one chance to steal the spotlight) but of the band as a whole. Indeed, though the setlist contains "If I Was Your Girlfriend," which upends the love song along gender and romantic lines, the most transgressive and shocking moment of the whole film may come when Prince leaves to let his band have all the attention with a rendition of Charlie Parker's "Now's the Time."

Sign 'O' the Times (the album) has since become a convenient marker post for Prince fans to delineate his classic period from "the rest." (An overly restrictive assessment, one that ignores such gems as The Black Album, 3121 and pretty much the whole of his early '90s material, which has aged incredibly well. It also overlooks how much fluff Prince put out even in his golden period, but this is an argument for another article.) Nevertheless, the record certainly does feel like a snapshot of the artist at that stage of his career, and so too does this concert film. Prince's subsequent tour backing Lovesexy serves better as a curtain call for his '80s work, amping up both the porn and religious exaltation while sprinting through his vast catalog as if making his own mixtape. But Sign 'O' the Times is a better view of both the massive ambition and the raw skill and visceral impact of Prince's music. It is also a better forecast: its almost exclusively new material looks forward to the New Power Generation, and the return of the funk anticipates the Purple One's attempt to reclaim some of his black audience in the '90s after swinging so fully into outright pop. Yet its base impulse, to acknowledge concerns of nuclear annihilation and then push those fears out of mind with carnal pleasure and spiritual salvation, represents the pinnacle of Prince's fundamental musical drive in the '80s. The film ends with a rousing version of "The Cross," but it could just as easily have concluded with the great "1999" and the desperate optimism of its line, "I don't wanna die/I'd rather dance my life away."