When entering a trade, there are several different types of orders you can enter. Whether doing this via a website or calling a broker on the phone, understanding what the different types of orders are and what the jargon means is important. In this article, we’ll talk about what market and limit orders are and which one you should use when. Note that this applies mainly to single stocks instead of mutual funds, although if you’re entering orders for an ETF they may become important as well. This is just a primer; there is a lot more to learn about stock investing. To learn a lot more, including how all of the main investment options work, please check out The SmallIvy Book of Investing.

(Note, this site contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. When you click on an affiliate link and buy something, The Small Investor will get a small commission for the referral. You are charged nothing extra for the purchase. This helps keep The Small Investor going and free. I don’t recommend any products I do not fully support. If you would like to help but don’t see anything you need, feel free to visit Amazon through this link and buy whatever you wish. The Small Investor will get a small commission when you do, again at no cost to you.)

What’s the spread? How markets work.

Before going into the orders, let’s talk about how markets work. In a market there are people wanting to sell and people wanting to buy. Those who want to sell ask a certain price for their shares. Those who want to buy place a bid for the shares. These are called the ask and bid prices. When someone has the same ask price as someone else’s bid price, a transaction is made and shares are exchanged. There are also people called market makers who buy and sell shares for their own profit, which makes trades happen more often and helps increase the ability of people to buy and sell their shares.

At any time, there will be a bid and an ask price for a virtually every stock in the markets with the bid price always being less than the ask price. Remember that the bid price is the highest price that someone is willing to pay to buy the shares and the ask price is the lowest price for which someone is willing to sell his shares, so if the bid were more than the ask, the person selling his shares would sell them to the bidder, those shares would no longer be available for sale, and the ask price would move up to whatever the next person was willing to sell his shares for.

Once a trade is made, the price at which the trade was made becomes the last price, which is the price that most people are talking about when they say that a stock is at a certain price. For example, when you say that your stock is up $1 for the day, you’re saying that the stock last sold for a dollar more than the last trade made the day before. The last trade for the previous day is called the previous close.

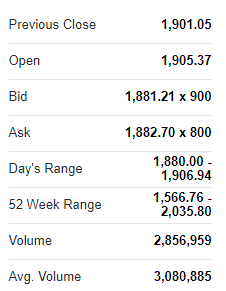

As an example, let’s look at a full quotation for Amazon, as provided by Yahoo Business:

Here we see first the previous close, which is the price at which Amazon stock last traded on Jan 9th. We then see the open, which is the price at which the shares first traded at today. Notice that the stock traded about $4 higher today than the last trade yesterday, showing that prices can jump by a fair amount between trades and between closing one day and opening the next, so just because you were able to get shares of Amazon yesterday at $1901 doesn’t mean you’ll be able to get the same price today. The previous price is a good reference of what someone may be will to sell the shares for today, but it doesn’t mean that there definitely will be someone willing to sell them for that price.

We then see the bid and the ask price. Note that there is also a “x 900” after the bid price and a “x 800” after the ask price. This means that there are people wanting to buy 900 shares at the bid price and 800 shares for sale at the ask price. Note, if more than one person is wanting to sell shares, the first person to put in the order would sell his shares first. For example, maybe there is one person wanting to sell 300 shares and another wanting to sell 500 shares. If someone came in wanting to buy 400 shares, he would get 300 shares from the first person and the other 100 shares from the second, leaving the second person with 400 more shares to still be sold.

(Want to become an expert in single stock investing, plus learn what you need to be doing at each stage of life to grow wealthy? Get a copy of The SmallIvy Book of Investing.)

The difference between the bid and the ask price is called the spread. In this case, the spread is equal to $1882.7 – 1881.21 = $1.49. The bigger the spread, the less likely shares are to be sold because the farther apart buyers and sellers are on price. But the market makers also make money by buying at the bid price and selling as the ask price, so they like to have a large spread. Before about the year 2000, stocks were quoted in fractions with 1/8 being the smallest fraction used for stocks above about $10 per share. This ensured a spread of at least $0.125. The system was changed to using pennies instead around that time to try to make the spread smaller and save investors money.

In this case we see that the bid and the ask are way below the opening price of $1905 and the previous closing price of $1901. This means that the stock will probably trade at lower prices and be down in price on the day. Until it trades, however, the quote that you will see if you just type AMZN in your broker’s app will stay at that of the last trade, so you would be unaware that the bid and ask had moved lower unless you looked up the full quote like this.

This quote also shows the day’s range, which is the high and low price at which shares have actually changed hands today and the 52 week range, which shows the prices at which shares have been bought and sold over the last year. This information can be used to help judge the range of prices at which it may trade and help you determine what price you should offer to pay/accept. Remember, however, that this is just a reference and just because someone was willing to pay $1906.94 earlier in the day doesn’t mean that someone else will be willing to do so again.

Finally, the volume is shown, both the volume today and the average volume. This is the number of shares that have traded today and the number of shares that trade on an average day. The higher the volume, the easier it is to buy and sell shares since there are a lot of people in the market (or someone is unloading a bunch of shares). Because someone selling one share can cause the last price to change, you can also use volume to determine if a price move is significant. If you see the price jump but there is no volume, it probably doesn’t mean anything. If it jumps and there is lots of volume compared to the average, however, it may show that something big is happening and it would be worth it to check the news.

What is a market order?

The simplest type of order you can enter is a market order. If you don’t say anything, most brokers will enter market orders by default. In a market order, if you put in an order to buy, you’ll pay whatever the current ask price is for the shares. For example, if you put in a market order to buy 300 Amazon shares right now, you’d get the shares for $1882.70. This assumes that there were enough shares available at that price by the time you entered the order. If someone came in before you and bought 700 of the 800 shares available at the current ask price, the price you’d pay would go up since you’d pay whatever the next higher ask price was after the shares selling at $1882.70 were all sold.

If you were selling shares and put in a market order, the sale would be executed at whatever the bid price was right now. Again, if all of the shares at the current bid price were sold, you would sell your shares at the next lower bid price, continuing in this manner until all of your shares were sold. What if you didn’t want to sell the shares unless you got a certain price? In that case, you might enter a limit order.

What is a limit order

If you put in a limit order, you’re saying that you will not buy (or sell) the shares unless they are at or below (above) a certain price you set called the limit. For example, you could tell your broker that you want to sell 100 shares of Amazon with a limit of $1882. This would guarantee that you would get at least $1882 per share if and when they sold.

So, what would cause these shares to sell if you put in such an order? The bid price would need to be at $1882 per share or above and there would need to be enough shares available at that price to fill your order. For example, if someone came in and put in a bid to buy shares at $1882.50, you would sell your shares (up to the number the other person was wanting to buy) at $1882.50. Again, this assumes that you are the first person in line with a limit order at or below that price.

Expert tip: If there are not enough shares available, your broker will normally fill as much of your order as she can. This may not be what you want, especially if you get charged a flat commission whether you buy 10 shares or 100 shares. You can prevent this by putting in an all or none order, where the trade will only execute if you can get all of the shares. I find that this is not necessary unless I’m dealing with a stock that has low volume.

When, and when not, to put in a market order

There are good and bad times to use both market and limit orders. It might seem odd to place a market order since you don’t know the price you’ll pay (or get), but it is actually perfectly safe a lot of the time. Normally, you’ll get something close to the price at which the stock traded last. This is because there are lots of individuals in the market, throwing out bids and offers, plus people buying and selling their shares look at those prices and set their offers accordingly. Just like you would probably set the price of a used car you were trying to sell near the price for which someone else sold theirs, people trading stocks set limits near previous prices since they figure others would expect to trade near the same prices. The only times prices change rapidly is if there is some news that comes out, causing people to change the price they are willing to pay or sell their shares for. If great news comes out, people instantly raise the price, trying to figure out how much people will pay. If bad news comes out, holders of the stock may want to get out as fast as they can and drop the price quickly just to sell their shares. You can get an even better idea of what you’ll pay (or get) by looking at the current bid and ask prices just before you place the trade.

Good times to put in a market order are:

- The stock you’re trading always has lots of volume, meaning there are lots of people buying and selling shares every day.

- You think that the price is cheap (if you’re buying) or high (if you’re selling), such that you really want to get in or out before people come to their senses and move to a more reasonable price.

- You want to be sure to get in or out. You may want to be sure to get in if you think shares are cheap or you want to invest some money quickly to make sure you don’t get left behind. You may want to get out quickly if you’ve made a good profit and don’t want to see the share price go back down before you sell.

- You don’t want to waste time adjusting your order. You just want to get it done and get on with other things, so you’ll give up an extra $25 or $50 on a $2000 trade.

Bad times to use a market order are when:

- The stock does not have a lot of volume, meaning there are only a few buyers and sellers. In this case, the stock can change in price drastically, particularly if you’re buying or selling a lot of shares.

- The size of your buy or sale is large compared to the trading volume of the stock. In this case the trade you are making will make the share price change significantly, making you get a bad price. All or none is also important in these situations.

When to put in a limit order

Limit orders also have their uses and can help you make a little more on each trade. If you’re investing long-term, as suggested in FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early , it really won’t make much of a difference and it is dangerous to miss getting in or out, making it worth it to just enter market orders and perhaps pay an extra quarter point for a stock. I put in market orders most of the time when I’m buying shares so that I know I’ll get the shares. But there are situations where you can really get hurt if you use a market order and a limit is more appropriate.

FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early

Times where a limit order makes sense:

- You’re buying or selling a stock that does not have a lot of volume, meaning the price you pay or get could change rapidly and even your order could move the price of the stock.

- You’re buying a stock and you only have a certain amount to invest. For example, you have $2000 in an IRA to invest and can’t add more until next year, so you need to make sure you don’t pay more than $2000.

- You’re accumulating shares of a stock over time and want to buy more if it drops below a certain price.

- You’re selling shares to trim your position and want to sell if it goes above a certain price, but are happy to hold it if not.

Note in these last two cases especially, you’ll want to tell your broker that the order is Good ’til cancelled or GTC. Otherwise it will be considered a day order and you’ll need to enter it again tomorrow if the order doesn’t execute today. GTC orders stay active for a period of months.

Times when you don’t want to use a limit order:

- You’ve made a good profit and want to take money off of the table to protect yourself. You might save a hundred dollars with a limit order, but you could lose thousands if the stock doesn’t reach your limit and falls precipitously.

- A stock is at a good price and you want to get in.

- You’re doing a stop loss order.

In this last case, a stop loss order, you are creating an order to protect yourself should a stock drop below a certain price. For example, if stock XYZ drops to $20 or below, you want to create an automatic order to sell the shares. You can create both stop loss limit and market orders. If you set a stop loss limit order, you’ll create a limit order at $20 if the stop price is hit, meaning that if it fell to $19 and triggered your stop loss, you would create a limit order to sell at $20. If the stock continued to fall and never hit $20 again, you’d keep losing money. You thought you were protected, but you really weren’t!

To prevent this, you should use market orders with stop loss orders. If you set a stop loss market order, it would sell at whatever price it was at after reaching $20 per share or lower. This could still bite you in the case of flash crashes where stocks drop quickly due to a computerized trade for a few seconds or minutes and then bounce right back, but these are extremely rare and measures have been put in place to make these less likely than they were ten or twenty years ago.

Tips on setting limits

A good way to determine where to set a limit is to go back to the bid/ask spread. If you’re buying, for example, and kind of want to buy in but wouldn’t mind it if you missed out, you might set a limit at the current bid price. If you are more eager to buy, you might set it right between the bid and the ask price. If you really want to get in but don’t want to see the stock jump in price when you do, you might set it at or slightly above the ask price.

If you are accumulating shares, you might set a limit order a few dollars or maybe 10% down from the price at which you first bought in to add more shares if the stock drops. For example, if you’re buying XYZ, which is trading at $20 per share, and want to accumulate 1000 shares, you might first buy 200 shares at $20 with a market order and then set a limit to buy 200 more shares at $18 per share. If you get that order executed, you might then set another order to buy 200 more at $17 per share, and so on. If the stock keeps retreating, you’ll keep getting more shares. If it goes up, you might just sit tight and let it go or you might set a higher limit still below the current price and wait for a dip in price.

Actually, I would set the first limit order at $18.07 or something like that in the above example. Why? I would think that there would probably be other people with limit orders in and they would probably set them at even dollar amounts since that is human nature. If someone else had an order in at $18 and I had one in at $18.07, I would get the shares. If I put it in at $18 and she were there first, she might get the shares instead of me before the stock bounced back up. So, instead of setting a limit at 418 or $18.25 or something, set it at $18.06 or $18.31.

(If you enjoy The Small Investor and want to support the cause, or you just want to learn how to become financially independent, please consider picking up a copy of my new book, FIREd by Fifty: How to Create the Cash Flow You Need to Retire Early This is the instruction manual on how to become financially independent.)

Have a burning investing question you’d like answered? Please send to [email protected] or leave in a comment.

Follow on Twitter to get news about new articles. @SmallIvy_SI

Disclaimer: This blog is not meant to give financial planning or tax advice. It gives general information on investment strategy, picking stocks, and generally managing money to build wealth. It is not a solicitation to buy or sell stocks or any security. Financial planning advice should be sought from a certified financial planner, which the author is not. Tax advice should be sought from a CPA. All investments involve risk and the reader as urged to consider risks carefully and seek the advice of experts if needed before investing.