Son Hayes (Michael Shannon) bears more scars than the shotgun marks on his back. His monosyllabic name, a description more than an identity, speaks to a childhood of neglect as much as his terse self-sufficiency. We meet him as he discovers his wife has left him, silently reacting to this awareness as if having long expected it. She wouldn't be the first person to walk out on him, whether or not he deserved it. With her gone, Son invites his similarly monikered brothers, Boy and Kid, to come live with him. The reluctance on Shannon's face communicates a primal sense of filial obligation more than any real kindness for his homeless siblings.

Son Hayes (Michael Shannon) bears more scars than the shotgun marks on his back. His monosyllabic name, a description more than an identity, speaks to a childhood of neglect as much as his terse self-sufficiency. We meet him as he discovers his wife has left him, silently reacting to this awareness as if having long expected it. She wouldn't be the first person to walk out on him, whether or not he deserved it. With her gone, Son invites his similarly monikered brothers, Boy and Kid, to come live with him. The reluctance on Shannon's face communicates a primal sense of filial obligation more than any real kindness for his homeless siblings.When word comes that the father who abandoned them as children died, they show up at the funeral in dirty work clothes to find the man's second family, the one he made after getting sober and finding Jesus, sitting apprehensively. Son says some harsh things about the father his half-brothers remember as a kind and loving man, standing before them as the skeleton from Pa's closet. At last, he spits on the coffin, catalyzing an inevitable feud that will have horrific consequences.

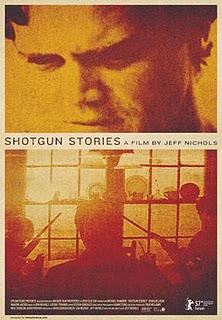

Jeff Nichols' Faulknerian debut Shotgun Stories creates a bleak atmosphere of its Arkansas setting, swapping David Gordon Green's rust-belt North Carolina for agricultural plains, where even a college boy knows how to fix a tractor. Gray skies hang over still fields of muted brownish-green. Poverty is an ingrained way of life, with Kid living in a camping tent outside Son's house and Boy in a van with a busted tapedeck and a battery he uses to run a salvaged window A/C unit and a margarita blender. Boy asks Son to use his VCR, but the older brother says that privilege comes with a price: a bag of Doritos.

When a character outside the fraternal conflict enters the frame, they bring only further coldness rather than a breath of fresh air. The father's first wife, who raised Son and the other two boys, lowers the already frigid temperatures into the realm of absolute zero, sucking out any hint of life with her hateful indifference to the plight of her boys before and after the altercation with the other Hayeses gets out of hand. Then there's Shampoo, who seems to come around only to let slip some new bit of gossip about the four half-brothers that reignites issues that previously hinted at settling.

Soon the insular conflict heats up, becoming so fierce it's easy to forget just how small and petty the squabble truly is. The second Hayes family cannot appreciate that the man they loved essentially ruined these three men, who in turn cannot respect that he did change and make a positive mark on the others' lives. The narrow-mindedness awakens the most destructive masculine tendencies in all of them. Well, most of them anyway, but the brother in each respective camp who tries to broker some kind of peace between the rest gets rebuffed by ally and foe alike.

"You raised us to hate those boys, and we do," Son tells his mother when the feud escalates into dire consequences. "And now it's come to this." Though Nichols elides over the violence, preferring to let a close-up of the drawing of a knife tell the audience what's about to happen rather than show the result, Shotgun Stories feels brutal and direct. Yet its lyrical quality also prevents the film from falling fully into despair. Son and Mark cannot lose face face before the other, but even when the situation spirals out of control and only deepens everyone's resolve, the men give off a sense of reluctance to continue. Bound to fight a conflict out of innate feelings of necessity, these brothers' fight seems a microcosm of so many conflicts great and small, and their conscious selves struggle against this primal urge. Some of them clearly have no clue even how to fight these battles, buying shotguns and looking at the pieces in confusion when it comes to assembling them.

That a small measure of decency manages to worm its way through the film's permafrost communicates some vague hope for concluding these seemingly unending battles, even as it does not even pretend to be an upbeat conclusion to the senseless violence. This is but the cautious first step, and there's no way to know if this is the start of a brighter dawn or merely the calm before the next storm.