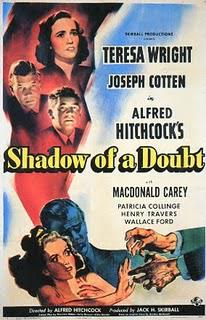

The theme of duality runs indirectly through many Hitchcock films, with the ironic alignment of two individuals in his wrong-man thrillers and the fetished quasi-double (who is really just one person period) in Vertigo. In films such as Strangers on a Train and Psycho, however, that theme has come more prominently to the fore, examined in moral terms in the former and ludicrously psychosexual in the latter. Shadow of a Doubt, Hitch's 1943 thriller widely considered his first masterpiece, is the director's purest exploration into this minor theme. Featuring matched action and edits, suggestive character unity and clashing moralities, Shadow of a Doubt is one of the director's more immediately guessable mysteries even as it is one of his most surprising pictures.

The theme of duality runs indirectly through many Hitchcock films, with the ironic alignment of two individuals in his wrong-man thrillers and the fetished quasi-double (who is really just one person period) in Vertigo. In films such as Strangers on a Train and Psycho, however, that theme has come more prominently to the fore, examined in moral terms in the former and ludicrously psychosexual in the latter. Shadow of a Doubt, Hitch's 1943 thriller widely considered his first masterpiece, is the director's purest exploration into this minor theme. Featuring matched action and edits, suggestive character unity and clashing moralities, Shadow of a Doubt is one of the director's more immediately guessable mysteries even as it is one of his most surprising pictures.Hitchcock establishes his darker tone instantly, opening on shots of urban decay in Philadelphia. And when his camera makes its way to a neighborhood where kids innocently play ball in the streets, the camera suddenly moves in a series of dissolves and low-angle Dutch shots upward into the no. 13 building nearby, finally moving inside an apartment where Charlie Oakley (Joseph Cotten), going by an alias, lies on his bed with liquor and money casually placed on the bed table. Cotten looks like a vampire, an image strengthened when the landlady arrives and closes his blinds, the darkness cause the man to rise with a jolt. The woman acts like a chiding mother, lovingly cleaning up the place and speaking to him sweetly without picking up on the harshness of his answering tone or properly paying attention to the implications of his littered alcohol and cash. She notes that two men came by looking for him earlier, and when she leaves, Charlie downs his last bit of whiskey and flees. Hitchcock was the master of paranoia, and the speed with which he undermines any expectation gives Shadow an edge that clearly announces the second stage of his career.

Shortly after this opening, Hitchcock begins mirroring shots and characters. Looking for a place to hide away, Charlie sends word to his family in Santa Rosa, California, and Hitchcock moves to that house using the same nearing dissolves to move inside the Newton home. Inside, he makes his way to the bedroom of Charlotte (Teresa Wright), who also goes by the name Charlie. Her introduction roughly matches her namesake uncle's, but some details reverse in the reflection. Where the landlady made a matronly figure, the well-meaning fool speaking to Young Charlie is her father, and where Uncle Charlie lounged in loose bills of cash, Young Charlie speaks of matters of the soul.

This is but the first example of doubling and reflection, and soon the film suggests an outright psychic link between Young and Uncle Charlie when the girl's sudden thoughts about her uncle and her subsequent discovery of a telegram saying he will be coming to visit. Wright, who never looked more innocent, greets her uncle's arrival with pure elation, oblivious to just how sinister, angular and harsh Cotten's leering Uncle Charlie looks to her sweet, giddy energy. The contrast is so marked as to be perverse, which is exactly what Hitchcock wants. Where Young Charlie sees her oneness with her uncle as a charming example of spiritual fulfillment, both Cotten and Hitchcock depict Uncle Charlie as desiring a oneness of a more physical kind. When the uncle arrives, the father superstitiously asks him not to throw his hat on the bed, but Uncle Charlie barely waits for his brother-in-law to leave the room before chucking it on his niece's mattress. It's not only a moment of defiance and deliberate antagonism, it has the feel of a predator marking one's territory.

Though Hitchcock had been in America since 1940's Rebecca and Foreign Correspondent, but Shadow of a Doubt feels like his first resolutely "American" film, the first time the national backdrop became part of the story and part of the psychological framework of the themes. Undoubtedly, the director owed this to Thorton Wilder, that master of small-town America who wrote the film's original script. Of course, this being Hitchcock, Wilder's gift for finely observed portraits give way to rigid types that play with American clichés. This is quaint, small-town Americana, a place where the people are neither gibbering yokels nor refined intellectuals; the townsfolk are generally simple, a bit ignorant and if they do not seem as fresh-faced as Wright, that is only because Wright's radiance outshines all.

By setting up Santa Rosa as typical Americana, Hitchcock makes Uncle Charlie's arrival all the more unsettling. Cotten's vampiric shadow hangs over this movie, rage erupting behind his cold exterior in his attempts to keep his true identity from his family. Even Young Charlie cannot maintain her enthusiasm when her uncle shames her father at the bank where he works, loudly joking about embezzlement as co-workers begin to eye the hapless Joseph. When the two ostensible reporters make their way from Philadelphia to continue investigating Charlie, his niece must confront the truth of his character, a revelation long ago figured out by the audience. Her understanding allows the film to travel in even darker directions, such as a centerpiece scene of Cotten freezing over in cold fury at a dinner where he goes off on a calm but forceful rant about rich widows, his measured tone not even remotely masking the sadism of his words.

It's important to note that Hitchcock does not particularly structure this film as a mystery; Uncle Charlie's identity as the Merry Widow Murderer is obvious as soon as we learn that a serial killer is on the loose, and Cotten does nothing to disguise Charlie's true self. Instead, Hitchcock uses his clear evil as a bouncing-off point for his aesthetic duality. Hitch juxtaposes innocent with perverse, humble with arrogant, plain with preening. Wright's radiance illuminates even her low-lit scenes, while Cotten casts all into shadow. Hitchcock was always evoked emotion with ruthlessness, and the manner in which he upends Young Charlie's world is heartbreaking in its cruelty: the poor girl is so flabbergasted to see that her unity with her uncle is one of horrifically diametric opposites that she almost cannot see how Jack, the detective pursuing the killer, forms a reflection of her goodness, not its inverse like Uncle Charlie. Of course, it also wouldn't be a Hitchcock film without jokes, and the director here delights in gags involving twos. The best of which, surely, is the scene inside the 'Till Two club where doubles are ordered.

When the two detectives posing as reporters come to Santa Rosa, they con their way into the house by saying they want to do a story on a typical American family, to which the mother, Emma, ironically replies that she doesn't think they're typical. Yet the suggestion under Hitch's use of broad types and unforgiving humanity is that the twisted, Freudian incest of this family and the seedy elements lurking under pre-fab suburban cleanliness and conformity is common to all such towns. Hitchcock would only delve further into such perverse, paranoid matters after the war ended, but Shadow of a Doubt is not only his first major consolidation of such issues but one of his best. It shows a director in complete control of his look and tone; no wonder, then, that his trademark cameo in this feature is a shot of him at a bridge table literally holding all of the cards.