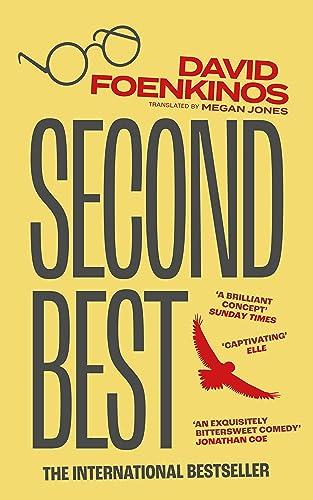

How much of your life would you ascribe to luck or fortune or destiny? Would you consider them even to be the same thing? For most of us, chance and coincidence play a minor role unless something extremely good or extremely bad happens, at which point we are thrown back on our feeble ability to make sense of the senseless and absurd. If this event happens in childhood, then it’s even harder to understand what has occurred. And if the disappointment suffered was so unique, so devastating, so obviously a shame to even the most disinterested spectator, it must be almost impossible. What if, then, at the tender age of 10, you made it to the final two actors in the casting of Harry Potter and didn’t get the role? This is the premise of David Foenkinos’s excellent novella, brilliantly translated by Megan Jones. It’s a slim, unpretentious easy read, and it punches far above its weight.

Martin Hill is the only child of mismatched parents – Jeanne, an ambitious French political journalist and John, a prop designer for the movies with a melancholy streak. They divorce when Martin is ten, and he travels back and forth to Paris for weekends spent with his mother. Martin finds his father’s film sets rather dull and there is no preordained reason he should end up in an audition, as the narrative voice, already attuned to the caprices of fate, reminds us:

‘Fate is always thought to be a positive force, propelling us towards a magical future. Surprisingly, its negative side is very rarely mentioned, as though fate has entrusted the management of its brand image to a PR genius. We always say, for example, “As luck would have it!” Which entirely obscures the idea that the things that luck would have are not always lucky.’

So two lucky/unlucky events occur for Martin. He ends up with round spectacles, and his babysitter on set has to rush home to attend her grandmother’s funeral. Other fateful events are also part of the concatenation of circumstances fomenting – we’re told about J.K. Rowling’s surprising journey into publishing, and David Heyman’s unlikely choice of the first Harry Potter book as a feature movie. All these plot lines eventually intersect at the moment when Martin is hanging about a film set, waiting to be an extra while his father is working. Heyman spots him and is struck by his appearance; he has the perfect look for the part. Screen tests then reveal him to be a natural actor. His parents can’t help but become excited. Martin can’t help but become excited. ‘The adventure seemed so real now; a miraculous life awaited him.’ But fate intervenes again. David Heyman now bumps into Daniel Radcliffe – his original choice for the part – with his parents at the theatre, and this time he manages to persuade them to let Daniel audition for the role, too. It’s a close contest between the two boys, but we all know how it’s going to come out. Daniel Radcliffe has a little ineffable something more. ‘This is how a human life can tip over to the wrong side. It is always something insignificant that makes the difference, the way the simple positioning of a comma can change the meaning of an eight-hundred-page novel.’ And Martin is fully aware of who has bested him, who has stood in his way. ‘Every person’s life is, at one moment or another, ruined by another person’s life.’

While I was reading this novella, I came across an article on the notion of invisible loss, written by the author of the term (and a book to go with it), Christina Rasmussen. ‘Invisible loss,’ she writes, ‘is a profound yet frequently neglected form of grief that arises when we perceive ourselves to be overlooked, misinterpreted, or discounted by the world. This subtle and persistent emotion defies easy definition, manifesting as pervasive feelings of anxiety, sadness, angst, or restlessness. In essence, it is a type of loss, a result of encounters that alter our self-perception.’ Rasmussen has much smaller disasters in mind here than the loss of a movie role that will catapult an actor to global stardom. But her concept attests to the way that losses we might tell ourselves are unimportant and should be sucked up can, in fact, leave long-lasting damage. The key, I think, is in this idea of an altered self-perception. The loss of the Harry Potter role completely alters Martin’s perception of himself: he can only see himself through the lens of this failure and it starts to pervade his entire life.

This is mostly because the Harry Potter phenomenon is itself utterly pervasive. Martin can’t bear to hear about the books or the films or anything to do with J. K. Rowling and, in the midst of global Potter fever, this turns him into a reclusive child, vulnerable and phobic. Poor Martin. He hasn’t told anyone at school about his auditions and so he can’t explain his aversion – a relief in some ways, a suffocation in others. The rest of the novel details the trajectory of his life into adulthood as he increasingly suffers from his issues and then tries everything he can, running the full tragicomic gamut, to fix them. For most of the time, his problems seem insurmountable, but the solution, (also the ending of the book) is creative, satisfying and really quite perfect. Aptly, I didn’t see it coming.

Foenkinos is asking us some powerful questions here about success, failure and achievement, and whether we really understand what they are or how to deal with them. ‘These days we live under the tyranny of other people’s happiness,’ the narrator tells us. ‘Or their supposed happiness in any case.’ The constructed reality of social media stands in too often for something genuine and authentic, which might look entirely different. Proper contentment could be as invisible as some forms of loss. But what this book really deals with is the other kind of tyranny exerted by the things we seek to avoid. Martin’s extreme tenderness about anything to do with Harry Potter relentlessly narrows his life. But it’s more than that. The failure robs him of his compassionate self-awareness. He can’t see his own life clearly any more, misreads its potential, condemns himself to a kind of cosmic persecution. He is no longer himself. Martin’s story is extreme, but Foenkinos invites us to consider how often we self-sabotage in this way over smaller matters. How many times do we let our lives shrink in the name of an anxious avoidance that doesn’t warrant the power with which we bestow it?

I remember reading somewhere (I forget where) that when we catastrophise, imagining bad things happening in our future, we put ourselves entirely at their mercy because we tend to think of them in isolation from our lives, out of context, undiluted by other happenings, unmitigated by consolations and compensations we haven’t thought of. The same is true for success. We tend to picture that in isolation too, in a kind of purity of perfection that we never truly experience. We also think of them both as static states, rather than fleeting moments, overriding the true dynamism of life in order to insist upon a false, unchanging persistence. But maybe this kind of self-sabotage is in fact a way to keep illusory control over our lives, rather than understand the extent to which luck and chance randomly guide them. At least failure and success are notions we can fully own, outcomes for which we can deem ourselves entirely responsible. Foenkinos, in his clever account of Martin’s fate shows us that we often get luck and control assigned the wrong way round, especially in intense and life-changing moments. But this is a novella with real heart and ultimately, it instructs us to trust to life’s unfolding. The humble realisation that our interpretations of the things that happen to us are partial at best, is our saving grace.