Searching for Authenticity in Jackson Heights

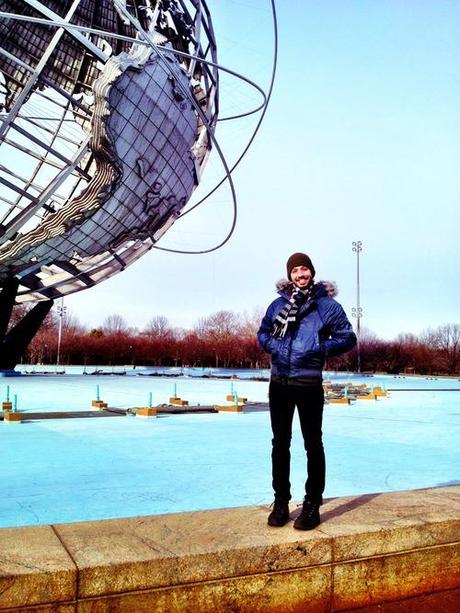

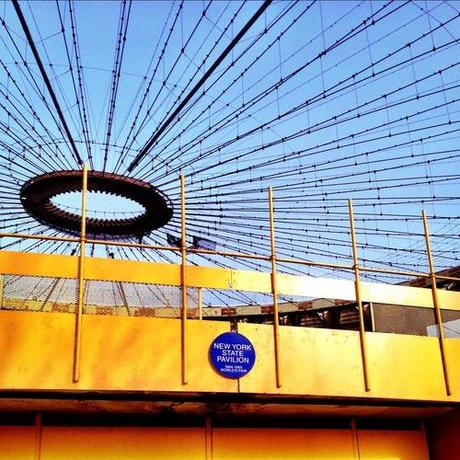

For a long time now, Caleb has wanted to go to the Flushing Meadows Park, where the World’s Fair was held in 1964. Some relics of the event remain; a huge silver globe and the New York State Pavilion, which you’ll probably recognize, if you were a child of the 1990s, from the film Men in Black.

From the BQE, they appear to loom like spaceships over a stretch of wasteland suffocated by the roadway arteries that lead up to the city.

Up close, however, the globe — known as the “Unisphere — is something of a tourist attraction. You know the type. A bland monumental structure lent drama by the carefully manicured landscape surrounding it — the sort of place where tour buses stop out of desperation. It reminded me, for example, of the India Gate in New Delhi. On Saturday, it was only 25 degrees Fahrenheit, and still, there were at least five families crawling over the structure, taking pictures.

The pavilion, however, has fallen into dereliction, and it is far more beautiful. Through the bright yellow gate, it looks like a haunted carnival ground. The feel of it, gloomy and easily penetrable, reminded me of the atrium of the Colosseum. That sounds like sacrilege, but its the goddamn truth. I don’t know why I’m writing so much about this, because you should never visit it, it’s very boring.

After we made a quick round of the park — and Franke had thoroughly marked her territory in tiny spurts of urine — we headed over to Jackson Heights, where Caleb had heard you can get “authentic” Indian food.

One of the things that drives me the most crazy about hipster culture is the search for “authenticity.” It’s not enough to buy a bike; you have to buy a bike from 1968 when fucking, I don’t know, cork handlebars were invented or some shit. It’s not enough to buy a fucking working record; you have to buy the original copy of the record because the plastic taste better when you eat it. (What, you don’t eat records?) It’s not enough to like tasty Indian food; you have to like the Indian food that taxi drivers eat in the neighborhoods where they live, because then, and only then, is it truly authentic.

Can I tell you a secret? Those taxi drivers aren’t eating the food because it’s authentic. They’re eating the food because it’s cheap and it’s near where they live. The people who own those restaurants aren’t making authentic restaurants; they making restaurants that serve the food they know how to cook. One of the most shocking revelations I ever had while traveling is that local food is never the “best” food you’ve ever had from that culture. The best food you’ve ever had from any culture is probably being made in fucking Tokyo, where all of the food, even the French food, tastes better than the country from which it originated.

I’m in a fucking ranting mood today, I don’t know why.

Anyway, Caleb is sort of a gigantic hipster, and his quest for authenticity is usually met with my scorn and derision. “Do you smell the curry in the air?” he asked me when we drove onto the main street in Jackson Heights, which, by the way, stretches for less than a city block.

“Not really,” I said.

We had just taken the long way from Jackson Heights down Roosevelt, which runs underneath the platform for the 7 train. On both sides of the busy thoroughfare were microscopic neighborhoods, which bled into each other like shades on a color wheel. First there was the Mexican hood, and then, the Peruvian. After, the Colombian, and then the Chinese. In each neighborhood, there were grocery stores and restaurants and discount shoe places and waxing parlors. There were also competing dive bars, inside which bleary eyed alcoholics, the same in every culture, sunk into their fifth or sixth afternoon beer. There’s something truly amazing about driving in a straight line, and seeing how the landscape changes based on ethnicities; in New York, it’s the most beautiful thing an outsider can come see.

Caleb left me in the car with Franke, and went out on a foraging mission for lunch. Franke barked at people as they passed; I lackadaisically flipped through the Daily Mail on my iPhone. Ten minutes later, and Caleb was back. “I found the most amazing Thali place,” he gushed, beaming.

The last time I ate Thali food was at a restaurant in New Delhi — there, the entrance was blocked by a swarm of flies so large that walking through it felt like being pelted in the face with uncooked popcorn. “Great,” I said.

“You should see this place, it’s awesome,” he said. Then he drove us around the corner to go pick it up. When we arrived, I saw that the restaurant, rather than being the most awesome place ever, looked just like a Chinese food take-out place in Crown Heights, only the sign was in Hindi. “Trust me,” Caleb said. “It’s going to be delicious.”

We took the food home, and set it out on the table. For $14, it was quite a spread. Caleb picked tiny pieces of each dish as he placed them on our respective plates. “Brie, you have to taste this!” he screamed each time.

When he was done, I looked down at my meal. It was all in shades of brown, except for the rice and bread. It tasted brownish too; earthy and heavy. (Reading that over it sounds totally racist; I don’t mean it at all offensively.) “This is good,” I told Caleb as I tried to eat “authentically,” by which I mean with my fingers only. In India, men eat with their right hands; their left, they tuck behind their backs, because that hand is used for wiping after shitting.

“This is the best Indian food I’ve ever eaten in New York!!” he proclaimed.

I turned to him. “Caleb,” I said. “Come on.”

“Where have you had better Indian food than this?” he asked.

“Lots of places,” I said.

“Name one,” he said.

“No,” I told him. Because honestly the only one I could remember was Tamarind, and I knew he was going to call me out because it’s relatively expensive.

“Caleb, I know this isn’t the best Indian food you’ve ever had,” I said. I also knew the best Indian food he ever had certainly wasn’t in India, where he was frequently troubled with explosive diarrhea.

“It is,” he told me, stubbornly. “I’ve never eaten better Indian food in my entire life.”

One of the things that I love the most about Caleb is that in any given argument, he really holds his ground, which is more than I can say for most people.

“You know you’re just saying this because you think it’s authentic,” I told him. He threw up his arms, and without meaning to, revealed the gigantic record collection on the wall behind him.

“I’m not,” he said again.

“You know what,” I told him. “I love you. Thank you for today.” And that I really meant. Because the whole reason why we went anywhere at all on Saturday was because I was depressed; Caleb knew that a drive somewhere in the car would make me feel better. And it really did. My gratitude itself was authentic.