Version 1.0.0

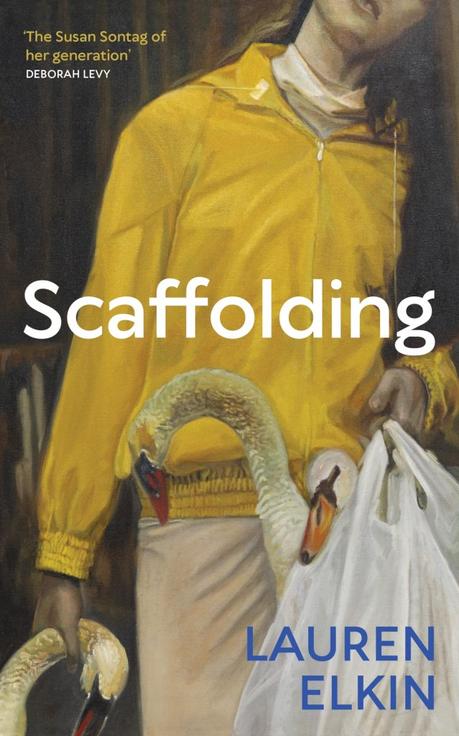

" data-orig-size="1598,2560" sizes="(max-width: 639px) 100vw, 639px" data-image-title="Version 1.0.0" data-orig-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg" style="width:348px;height:auto" data-image-description="" data-image-meta="{"aperture":"0","credit":"","camera":"","caption":"Version 1.0.0","created_timestamp":"0","copyright":"","focal_length":"0","iso":"0","shutter_speed":"0","title":"Version 1.0.0","orientation":"0"}" width="639" data-medium-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=187" data-permalink="https://litlove.wordpress.com/2024/12/03/scaffolding-by-lauren-elkin/version-1-0-0/" alt="" height="1023" srcset="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=639 639w, https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=1278 1278w, https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=94 94w, https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=187 187w, https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=768 768w" class="wp-image-5057" data-large-file="https://litlove.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/81imac7yd2l.jpg?w=440" />Reading Scaffolding made me think of a Nouvel Observateur article in which French intellectuals, Julia Kristeva and Philippe Sollers, discussed their open marriage in a era in which the term polyamory had yet to take root. Unrepentant about his multiple mistresses, Sollers shrugged and said, ‘Mais, qu’est ce que c’est la fidélité?‘ And seemed inclined to mean it. This provoked a lot of eye rolling about French people in black polo necks, when almost anybody could give a definition of faithfulness without making a puzzle of it. Elkin’s novel is inclined to revisit the question of fidelity too, taking the wavering trajectory of desire as its central focus. If it had been just about adultery, I might well have skipped it, given my menopausal weariness with all things Romance. But it’s a tisane of a novel, steeped in French settings and French ideas, with Elkin’s main characters both students of the psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan no less, that most obscure and difficult of French theorists. Anyone can write a novel about adultery, but to throw Lacan in the mix raises the demand on exposition to a different order of magnitude. And so I decided I needed to read it.

The novel revolves around two couples who live in the same apartment in Belleville, several decades apart. The present day story line concerns psychotherapist, Anna, who is on medical leave after a mild breakdown in the wake of a miscarriage. Her husband, David, has gone to London to do something Brexit-related (David gets short shrift, I’ll warn you now), and Anna has stayed behind despite the fact that the facade of the apartment building is being renovated (a necessary evil of living in Paris). At the same time, they are having their old-fashioned kitchen remodelled. In the midst of highly symbolic chaos, rubble and noise, Anna is drifting untethered, lost to a strange upsurge of memories about a previous lover, Jonathan, whose father was instrumental in her choice of career as a therapist. At the same time, she meets Clementine, a young woman who also lives in the building, and whose sparky, youthful vitality is deeply attractive. They become friends.

A recurring trope in French novels is the split between characters who think and characters who do – a legacy of Existentialism and its prequels through the ages. Anna admits: ‘I think about things, but I don’t do anything about it.’ Whereas Clementine is in a rush of life, studying art history, interested in ideas, and one of the band of feminist colleuses, who stick posters up around Paris raising awareness of violent acts committed against women. She’s also probably sleeping with other women despite having a long term male partner she lives with. Things get complicated when the long-term partner turns out to be Anna’s former lover, Jonathan.

At this point we shift time frames and discover the lives of Florence and Henry, a young married couple occupying the same apartment in the early 1970s. Henry, a conventional male bottler of emotion, is deeply in love with his wife, the free-spirited Florence. She’s a student of the Maestro, Lacan, and, alas, having sex with her professor, Max, at the university. In this section the narrative is handed back and forth between the married couple, with Henry documenting his discovery of the affair and his simmering jealousy, while Florence is deeply preoccupied with what it means for a woman to have genuine freedom. She wants a child, and Henry – whose Jewish family has recently had some traumatic entanglements with Hitler – does not. The situation builds between them to a shocking conclusion.

Before going any further, we need to pause and think about structures, the various kinds of scaffolding, that are intrinsic to the novel. There are two kinds of structure at work: the first is the container, designated by the walls of the building itself, which hold the lives of its occupants and which, in a form of emotional sympathy, are undergoing messy renovations. Anna talks of the ‘beautiful exoskeleton’ of the scaffold, ‘That testament to work, to remaking, to the possibility of transformation’. The building here is an analogy of the human mind in the therapeutic process, itself a container that is being worked on in the hope of transformation to something new and better.

The second kind of structure is the palimpsest, in which different layers – created at different moments in time – overlap across the same space, with older layers still visible, not fully effaced. This is where our couples overlap in time, and we see the same preoccupations with motherhood, with psychoanalysis, with love and sexuality and fidelity, with Jewishness, playing out in different ways.

And finally, we need to consider one more structure, and that’s the structural psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan. He believed that humans are structured by language, which forms but an imperfect net cast over what he called ‘the Real’, the very stuff of life from which we are separated as soon as we start to speak. Language is an arbitrary system that uses words to designate things; there’s no thingy essence that’s being expressed by it, no innate reason why we use one word rather than another. The map is not the territory. There is so much that we long to say and express, but language has its formulas and we can’t stretch them very far before we fall into incomprehensibility. We become, then, creatures of the gap, of the lacuna, forever unable to say what we mean, or mean what we say. This is one of the reasons why Lacan says that desire arises from lack. We are missing so much, and most of it – despite our frenzied rush from one thing to another, trying to fill up the empty spaces inside – can never be fulfilled.

The intellectual ambition of the novel is to overlap all three structures – time, space/place and concept – in a kind of three-dimensional crucible of desire. I applaud the ambition, but inevitably such complexity means that some parts of this work better than others. There’s a hefty weight of material asking for significant reverberation in the final section, if not outright resolution.

So, we leave Florence and Henry mid-crisis and return to Anna, who falls into a sexual relationship with Jonathan, first, and then Clementine, who offers an alternative to the Lacanian notion of desire. It’s not lack, she says, but ‘a surplus energy, a claustrophobia inside your skin.’ The truth value of these conceptualizations isn’t really tested. Inevitably, desire remains enigmatic and opaque by the end of the novel, a compelling motivator that feels like a petty tyrant within. Here’s where the novel seeks to be very French, as the partner-swapping aims optimistically towards harmlessness. Both Florence and Anna have a sense of entitlement with their desire, believing they have the right to explore its potential and to let it govern their decisions. ‘We are made of desire, made of what we don’t have,’ Anna says. ‘Giving in to desire is part of who we are. We can’t keep desire at a distance.’ Maybe I’m just not Francophile enough these days, but it felt to me like awkward self-justification, particularly when kindly, loyal David seemed to do nothing to ask for his cuckolding, and Anna chose openly not to tell him. If ethics are uncertain, then doing something we can put our hand up to seems to be the only well-flagged route to choose.

But then, for me, when the section on Anna turned to the shagging, I found myself losing a degree of interest in the novel. It felt like it had suddenly become a whole lot more… conventional, I suppose. In French novels, the divide between characters who do and characters who think provokes some of the most extraordinary plots in the history of literature. The doers have to come across some extreme barriers to be forced into contemplation, and the thinkers have to tap into some extreme desires to be forced into their own agency. In Scaffolding, if all we have as an answer to the griefs and sorrows of existence is adultery, well then, qu’est ce que c’est la fidélité? The queering of the adultery plot with Clementine perks the story up again, but it still felt to me as if desire was inhabiting the plot, rather than the characters. By the end, I wasn’t sure how to read that central section on Florence and Henry, except as an earlier revolution of the cosmic hamster wheel we are all stuck on, and I thought it wanted, and deserved, to be more than that. The structure of the container held good – the work clearly happened, as Anna got her happy ending. But the structure of the palimpsest was confused, never resolving into more than the sum of its parts. I wasn’t sure what to make of the colleuses either, fighting the good fight against male violence in a novel where the men came off worst, emotionally at least.

But, and it’s a big but. It’s too easy to criticize novels of ideas because they are so incredibly hard to write. The great triumph of Scaffolding is that it manages to encompass so many ideas, so many difficult thoughts, just so much stuff, whilst being consistently readable and engaging. I listened to it (apologies if I’ve misquoted – it can be tricky to hear punctuation right) which might be the kiss of death to a less lucid narrative, and I turned up to every session of reading keen to know what would happen next, and keen to think about the mass of existential possibilities and intellectual ideas on offer. Being able to tussle with it a little was a pleasure, and there’s certainly nothing monolithic or didactic in Elkin’s writing. The novel invites our readerly desire to engage with it at every level. Lacan himself would surely approve.