My encounter with Kaayana in Kaa-Iya National Park in the Bolivian Chaco. Her cub was around but cannot be seen in the photo

I was trapped. Or so I thought.

The jaguar came towards me on the dirt road, calmly but attentively in the dusky light, her nearly full grown cub behind her. Nervous and with only a torch as defence, I held the light high above my head as she approached, trying to look taller. But she was merely curious; and, after 20 minutes, they left. I walked home in the thickening darkness, amazed at having come so close to South America’s top predator. We later named this mother jaguar ‘Kaayana’, because she lives inside Kaa-Iya National Park in the Bolivian Chaco. My fascination with jaguars has only grown since then, but the chances of encountering this incredible animal in the wild have shrunk even since that night.

A few years after that encounter, I’m back to study jaguars in the same forest, only now at the scale of the whole South American Gran Chaco. Jaguars are the third largest cats in the world and the top predators across Latin America. This means that they are essential for keeping ecosystems healthy. However, they are disappearing rapidly in parts of their range.

Understanding how and where the jaguar’s main threats — habitat destruction and hunting — affect them is fundamental to set appropriate strategies to save them. These threats are not only damaging on their own, but they sometimes act simultaneously in an area, potentially having impacts that are larger than their simple sum. For instance, a new road doesn’t only promote deforestation, it also increases hunters’ ability to get into previously inaccessible forests. Similarly, when the forest is cut for cattle ranching, ranchers often kill jaguars for fears of stock loss.

Kaayana was seen years later by Daniel Alarcón, who took much better photos of her and her new cubs

However, the interactions between these threats are still not fully understood. In our new study, just published in the journal Diversity and Distributions, we developed a new framework to quantify how and where habitat destruction and hunting risk acted together over three decades, at the expense of highly suitable jaguar habitat in the Gran Chaco. We also analyzed how well the different Chaco countries — Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina — and their protected areas maintained key jaguar habitat.

Gran Chaco dry forest

Although not as well-known, the 1.1 million km2 Gran Chaco is the second largest forest in South America after the Amazon. The Chaco is also, still, the largest tropical dry forest in the world, three times the size of Germany. The Chaco is rich in species diversity, with > 150 mammals, 220 reptiles and amphibians, 500 birds and 3500 plants.

Despite its global importance, the Chaco is under imminent threat, and < 10% of its forests and savannas are protected. Only over the last 20 years it has lost 20% of its forests, emitting as much carbon into the atmosphere as the Amazon and becoming a global deforestation hotspot. Most of this deforestation is either to produce beef, consumed locally and exported, or soy, mostly used for feeding cows, pigs and chicken in Europe and Asia.

Shrinking habitat

As part of my doctorate in the Conservation Biogeography group at Humboldt University of Berlin, where I moved two years ago from Bolivia, I teamed up with several other jaguar ecologists from across the Gran Chaco. Combining the authors’ years of research and experience, we built the most complete database of jaguar occurrence over the last three decades in the Chaco, along with the spatial information of the conditions that affect jaguars.

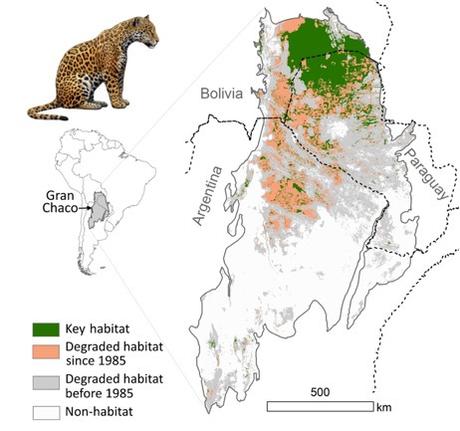

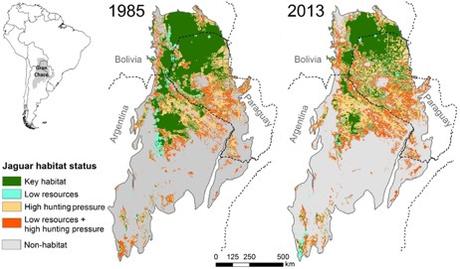

We used this breadth of information in computer models to build habitat maps that not only show where key habitat is, but also where jaguars are threatened by habitat destruction, hunting, or both threats simultaneously. Our approach allowed us to assess how habitat has changed since the 1980s across the entire Chaco, within countries, and inside and outside protected areas.

Jaguars lost the size of Austria of key habitat only since the 1980s due to the expansion of agriculture and overhunting

We found a large contraction of key jaguar habitat over three decades, amounting to an area the size of Austria (182,000 km2). We know this contraction was caused by habitat destruction and hunting, but which threat was more important and where did they interact? Interestingly, although both threats expanded rapidly over the three decades, the areas under hunting risk were larger (7 million hectares) than the areas under habitat destruction (3 million hectares). However, both threats acted together in a third of all the remaining jaguar range, and as both threats are interact there, jaguars are at higher risk of disappearing, if not already gone.

We also found that among the Gran Chaco countries, Bolivia lost less key jaguar habitat than Paraguay and Argentina. The main reason for this difference is probably the enormous, 3.4 million-hectare Kaa-Iya National Park, where I encountered Kaayana and her cub some years earlier.

Indeed, we found that larger protected areas lost proportionally less key habitat than smaller ones since the 1980s. This happens because smaller protected areas are more susceptible to the threats occurring in surrounding areas. For instance, because jaguars in the Chaco roam over huge areas, they can be killed by ranchers when they wander outside protected areas. However, even smaller protected areas still have a role, as 95% of all key jaguar habitat degradation occurred in unprotected areas. Furthermore, two-thirds of standing key habitat remains unprotected.

A more detailed view of how jaguar habitat changed between 1985 and 2013 in the Chaco. Key habitat shrunk by a third as hunting and resource deterioration (mainly deforestation) increased. Both threats acted simultaneously in the extensive red areas

Interestingly, most of the key habitat remaining by 2013 was located within 200 km of an international border, probably because these areas are marginal for development, and far from agricultural centres. However, agriculture and hunting are rapidly getting closer.

Conservation opportunities

Beyond describing the rapid decline of this essential predator of the Chaco, our study provides three main insights to save the jaguar in the Chaco:

- Governments and organisations of the three Chaco countries — Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina — should swiftly coordinate the protection of the large patches of key jaguar habitat that remain along international borders, while opportunities remain;

- Jaguar decline can be averted by reducing hunting pressure of jaguars and their prey in areas of high hunting risk but otherwise suitable forests, particularly along corridors connecting key habitats. An important way to do this is by improving the coexistence of jaguars with ranchers — a major source of jaguar mortality in the Chaco;

- The remaining large patches of key habitats, and the corridors connecting them, should be protected, preferably using a network of large protected areas. This will help to save the jaguar and much of the associated biodiversity in this rich, but under-protected ecoregion.

Our study shows that considering the interactions between agricultural expansion and hunting threats on the habitat of a top predator can help discern the patterns of threats across the landscape and over time. This in turn can help define broad-scale, multilateral conservation strategies to save the jaguar.

Given the extraordinary pace at which the top predator of the Chaco is declining, governments and environmental organisations should swiftly set up coordinated efforts while opportunities remain.

But what can individuals do to help jaguars? The rapid advance of deforestation and hunting in the Chaco is associated with the production of beef and soy. Meat, and especially beef, is one of the most inefficient foods to produce, requiring enormous areas of cut forests. Furthermore, in these deforestation frontiers, ranchers habitually kill jaguars for fears of cattle loss, further threatening jaguars.

Therefore, a safe way to help jaguars is by reducing our meat — especially beef — consumption. After thinking of the relation between my diet, deforestation, ranchers and jaguars, I have become mostly vegetarian and I now completely avoid beef. Eating beef only once or twice per month, or less, and in smaller portions could already help jaguars.

Fortunately, we confirmed that Kaayana still has good and safe habitat in her territory. We must ensure that other jaguars have this too.

Alfredo Romero-Muñoz, Conservation Biogeography lab, Humboldt University, Berlin