Book review by George Simmers. This book is made up of fourteen short stories, originally published in the penny magazine, The Weekly Tale-Teller. Wallace began as a journalist (including a stint as war correspondent in the Boer War) and had recently been to the Congo to report on the atrocities committed by the Belgians there. The editor of the Weekly Tale-Teller suggested he use his African experience for fiction, and the Sanders stories are the result.

They are set in Nigeria; I can’t discover whether Wallace ever actually visited that country. It seems likely that he didn’t, but was imagining it, as the alternative to the Congo. Instead of rapacious business interests looting the country, you have the decent, unselfish British administrator Sanders, whose job was to ‘keep a watchful eye upon some quarter of a million cannibal folk, who ten years before had regarded white men as we regard the unicorn.’ In story after story he heads up-river in a gunboat, with twenty loyal Houssa soldiers and a Maxim gun, and sorts out every problem that arises. His superiority to the Africans is never in question:

He governed a people three hundred miles beyond the fringe of civilization. Hesitation to act, delay in awarding punishment, either of these two things would have been mistaken for weakness amongst a people who had neither power to reason, nor will to excuse, nor any large charity.

‘By Sanders’ code you trusted all natives up to the same point, as you trust children,’ we are told, and his attitude to them is very much like that of attitude towards his pupils of the noble headmaster in public school stories of the period.

The book’s first story, ‘The Education of a King’, makes this clear. After the chief of a tribe is killed, Sanders makes sure that the chief’s son, Peter, a nine-year-old boy, succeeds him. When Peter’s advisors lead him into making war, Sanders comes along with his gunboat, but also with a cane. He gives Peter a thrashing, ‘This was the beginning of King Peter’s education, for thus was he taught obedience.’ Some years later Peter saves Sanders’s life, by giving up his own. I suppose this is exactly the vision of Empire that many of the British wanted to have – the imperialist earns the love of his subjects by being tough but decent and upright.

British rule is necessary, the stories demonstrate, because the various tribes are always at war, and some bully the others mercifully. Only the tireless vigilance and dedication of Sanders keeps the peace.

Sanders is the ideal imperial ruler, but the book also contains versions of how not to do it. These tales contain many variations of the Kipling story about an expert coming from London with abstract ideas about doing good, and then leaving a mess behind for the local administrator to clear up. There is Mr Niceman, for example, who believes in government by moral persuasion; he disappears from the narrative, but eventually there is a passing mention of ‘poor Niceman’s head, stuck on a pole before the king’s hut.’ Exploitative businessmen and traders who sell guns to the natives have to be dealt with in some stories, as do missionaries, who can be a destabilising influence. The worst is a black missionary called Kenneth McDolan, who not only spreads ideas about racial equality, but encourages the tribes to demand famine relief when there is not actually any famine.

If Christian missionaries are suspect, the African religions are shown as primitive – but sometimes their juju cremonies seem to work, so Sanders has is careful to show respect for them. Interestingly, the stories display quite a bit of respect for Islam, such as one finds in Kipling, too. Sanders’s Houssa policemen are men of the Prophet; it is a man’s religion, a soldier’s religion that imposes discipline. ‘The black men who wore the fez were subtle, but trustworthy; but the browny men of the Gold Coast, who talked English, wore European clothing, and called one another “Mr.” were Sanders’ pet abomination.’

As well as its superior attitude towards Africans, the stories include the other usual prejudices of the period; when crooked financiers feature in a story, we are told that one of them: ‘called himself McPherson every day of the year except on Yum Kippur, when he frankly admitted that he had been born Isaacs.’ There is misogyny, too. One story, ‘The Loves of M’Lino’ features an African femme fatale, who entraps two junior British officials, and then becomes the cause of tribal war. Women, like missionaries, are a destabilising influence.

There is one boundary-crossing character, though, that Wallace seems to have a soft spot for. Bosambo, imprisoned for theft in Liberia, escapes to Nigeria and sets himself up as chief of the Ocholi, a rather feeble tribe. He is unscrupulous and dishonest, but Sanders respects his intelligence, and they work well together.

The collection as a whole seems to me a simplification and vulgarisation of the less sympathetic bits of Kipling. But where Kipling knew India and had original things to say about it, Wallace is mostly retelling received opinions about Africa.

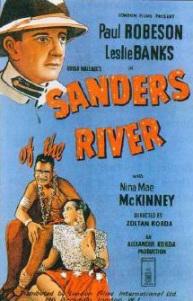

The book was immensely successful. It went into many editions, and there were eleven further collections of Sanders stories. There have also been films. First in 1921, The River of Stars seems to have used some of the characters, but seems to be a melodrama about a broken marriage. In 1935 there was Sanders of the River, by Alexander and Zoltan Korda, with Paul Robeson as Bosambo. When Robeson saw the finished film he was horrified by it. (I’m not surprised, having seen the complete movie on YouTube). He claims that the producers originally told him it would be all about the dignity of traditional African culture. Well, there are long scenes of apparently authentic Nigerian traditional dancing, but the end result is pure imperial propaganda.

In 1938 a Will Hay comedy Old Bones of the River uses the characters and themes of the books, mostly for slapstick comedy. This too is available on YouTube.

In 1963 Richard Todd played Sanders in Death Drums Along the River. The plot centres around diamond smugglers. There was a sequel in 1965, Coast of Skeletons.

The book is available free online from Project Gutenberg, as are some of its sequels.