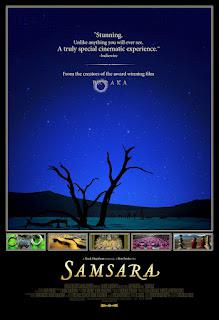

Ron Fricke's latest tone poem, Samsara, takes its name from a concept shared among Indian religions pertaining to life, death and rebirth. Its root in the constant change of the world fits the film's structure, which trades the focus of Fricke's own Baraka or Godfrey Reggio's Qatsi trilogy for a more free-associative collage of world imagery. Opening on jarring close-ups of a ritualistic dance performed by three little people, Samsara only gets more bewildering when it moves from this show to the eruption of a volcano and the cooling of lava.

Ron Fricke's latest tone poem, Samsara, takes its name from a concept shared among Indian religions pertaining to life, death and rebirth. Its root in the constant change of the world fits the film's structure, which trades the focus of Fricke's own Baraka or Godfrey Reggio's Qatsi trilogy for a more free-associative collage of world imagery. Opening on jarring close-ups of a ritualistic dance performed by three little people, Samsara only gets more bewildering when it moves from this show to the eruption of a volcano and the cooling of lava.Yet the titular idea also connotes a cyclical movement of life and rebirth, giving order to its vastness, and Samsara soon reveals its unifying theme to be that of various ordering properties. That opening dance, so bewildering as an introduction, soon becomes part of a larger tapestry of ritual, organization and routine of humanity in nature and urban development alike, and even those of the Earth. This explain the footage of the exploding magma and solidifying lava flows, a miniature cycle of destruction and reformation the planet has seen across hundreds of millions of years. Fricke even includes a near-bookend of Tibetan monks playing horns to wake their village, a sort of invocation and benediction that reflects the cycle of the film's loose subject matter and the organizing properties at work on all cultures.

Films like Koyaanisqatsi and Baraka tended to frame their key juxtapositions in the imbalance between "primitive life," with its proximity to (and, therefore, its respect for) nature and urban soullessness, in which people severed their bonds to the Earth but constructed giant, false jungles in a subconscious attempt to remake that which they had lost. Why, as seen in this film, man now makes its own mountains and islands, creating nature for our convenience. Samsara still compares the tribal to the globalized, but rather that show them as diametrically opposed, it positions them as like creatures differentiated only by scale. Rituals for the former may have more individualistic, artful expression than the time-lapsed gridlock and ultra-processed artificiality of the latter, but they serve the same purpose. Besides, the world now has modernized to such an extent that even those in the remote regions of the world have not escaped aspects of change. Near the end of the film, several Africans are seen holding AK-47s incongruous to their tribal tattoos and lip disks until one considers how long such a sight has been (sadly) all too common on the continent and how new weaponry merely marks a new era in centuries-old conflict, not the breaking of long-standing peace.

True, Samsara does have its montages filled with disturbing images of post-industrial life, in which seemingly everything can be manufactured on an assembly line. One shot of what appears to be the entrance to an amusement park gradually fills with hundreds of people all wearing the same color shirt. Just as I began to wonder why people waiting to get into a theme park would have the same outfit, I realized with horror that this was the infamous EUPA factory city in China, and the long line of like-clothed people were the workers. One shot inside a vast factory in this compound (with assembly lines making everything from George Foreman Grills to clothes irons) stretches into the vanishing point. More shocking is the similarity of the developed world's food preparation to this mechanized assembly. Some kind of combine harvester sucks up chickens and propels them into boxes, while pugs are strung up and gutted on a conveyer. Meat gets processed back in an enormous plant in China, and the journey ends at a Sam's Club in America. To drive the point home, Fricke throws in a time-lapse shot of fat Americans wolfing down Burger King in a food court, the sped-up factory work reflected in the unthinking rote of our consumption of cheap, fast crap.

Yet if Samsara suggests, as usual, that modernized humans have gone too far in claiming the Earth, it also implies that the Earth has always claimed us right back. Winds blow desert sands into an abandoned house; eventually it will be completely swallowed into a dune. A library hit by Katrina has its wares soaked and scattered, with a book spine reading "The Village That Allah Forgot" highlighted among the refuse. An Aborigine's hair is formed into dreadlocks by what appears to be red clay, making the human being seem like the dirt and dust all humans eventually become. The recurring image of a Buddhist sand mandala being carefully crafted and, ultimately, destroyed serves as an obvious visualization of this idea.

In such moments, Samsara may be more didactic than its forbears. Fricke's attempts at levity—Muslim women in niqabs standing beside a men's underwear ad with stripped-down models; a montage linking the manufacture of sex dolls, eerily emotionless androids and bikini-clad women with plastered-on smiles in a dance competition—leave as sour a taste in the mouth as that which he documents. At its best, Samsara signals a bold new direction for this film format, one that breaks from the already loose, evocative style to explore an interlinking network of ideas, to make these films about the breadth of life more resemble the chaotic but connected structure of it. At its worst, this is a ham-fisted number that trades a visually sumptuous lesson on one theme for a visually sumptuous lecture on many. Samsara's greatest strength is its occasional ambiguity, seen best in the level of beauty afforded to its silent appraisals of the developed world that always seemed so ugly in the film's predecessors. Having failed to beat this encroaching modernity back, Fricke finally gives it its due. Those aforementioned factory shots have a beauty to them as much as the hand-crafted temples and monuments that make for such breathtaking views elsewhere. Besides, those who made those astonishing wonders of the ancient world were even more hopelessly shackled to their task than the criminally underpaid workers in EUPA today.