Book Review by George S: Norbert Davis was an American author of detective fiction. I first heard of him when I was reading about Ludwig Wittgenstein’s taste in popular fiction. The great reclusive philosopher was (perhaps surprisingly) fond of P.G. Wodehouse, and also enjoyed a monthly subscription to Street and Smith’s Detective Magazine, which gave him a regular dose of hard-boiled detective thrillers. Norbert Davis was one of his favourites.

Norbert Davis is very much one of the tough-guy disenchanted thriller writers associated with magazines like Street and Smith’s and Black Mask; he differs, however, from authors like Dashiel Hammett and Cornell Woolrich in that his stories are often farcical.

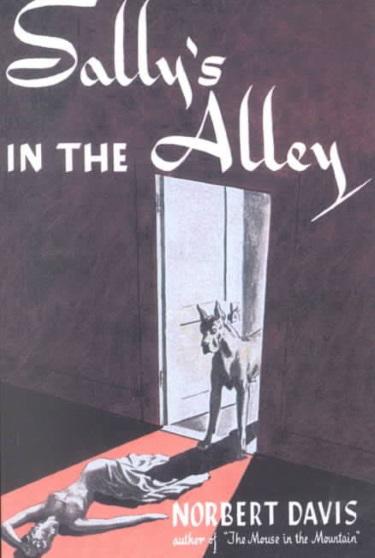

Sally’s in the Alley (1943) is the second of his novels to feature the detective Doan. Doan is sharp-witted, wisecracking and disrespectful of authority, just as a fictional private eye ought to be. He is different from most, though, in being accompanied everywhere he goes by a huge Great Dane called Carstairs.

The novel is a wartime thriller set partly in Hollywood and partly in a deeply corrupt town called Heliotrope, which is in either California or Nevada.

The State of California is now suing the State of Nevada in the Supreme Court to compel Nevada to annex it. Nevada has started a counter-suit to compel California to annex it.

Doan and Carstairs are sent there because Doan has been co-opted by the G-men to make contact with a dubious character called Dust-Mouth Haggerty. Dust-Mouth is supposed to know the location of deposits of a valuable ore that is useful in weapons production.

He will not reveal this location to the authorities, but wants to sell it to the highest bidder. Doan’s job is to pose as an agent for the Japanese government and offer him a lot of cash for the secret.

Even before Doan gets to meet Dust-Mouth, dead bodies start to turn up. He finds one in the trunk of his car, and another in his hotel room. Doan has no compunction in moving these to other locations, to frame people he doesn’t care for.

Everyone he comes across, in Hollywood or in Heliotrope, is corrupt. The police take bribes. Almost nobody is what he or she seems. The violence is extreme and often farcical, and the plot-twists come thick and fast. The solving of the murders at the end is as logical as it needs to be, and in the climax, Carstairs the dog, who up to now has been mostly an encumbrance, proves his worth by dealing effectively with the two perpetrators who are holding Doan and others at gunpoint.

So it’s a pretty satisfactory thriller, though not as good as the first Doan and Carstairs novel The Mouse and the Mountain, which is set in Mexico.

One thing that struck me was how different this is from the standard British detective story of the period. British thrillers may subtly undermine social certainties by revealing secrets underlying respectable facades, but they never have this amount of sheer disrespect for authority, or this amount of cynicism about social institutions.

I recently posted about J. Maclaren Ross’s Of Love and Hunger, which references James M. Cain as an example of American writing with a frankness and toughness that British writers don’t aspire to. Norbert Davis is not quite in the James M. Cain class – too farcical, too determined to play things for laughs, but you can see why British readers (and Wittgenstein) might have found his kind of story a useful antidote to British gentility.