The Best of Both Worlds

Toni Garrido as Orfeu

With his stirring defense of Cacá Diegues’ Orfeu resonating in the international press, Caetano Veloso inadvertently hit upon the chief catalyst for the film’s poor showing with English-speaking audiences,* but through a side argument: and that is, the music. Or rather, the lack of an identifiable musical theme or idea as a viable reference point for viewers.

What it all boils down to, quite simply, is this: where Marcel Camus’ 1959 version had no trouble ingratiating itself to the musical mainstream of its day — namely, the jazz-pop idiom, thanks largely to the pioneering efforts of Jobim, Moraes, Bonfá, and the rest of the Brazilian bossa-nova crowd — the Alagoan director’s elaborate excursion into socially relevant cinema benefited from no such windfall.

A sampling of the later film’s soundtrack bears this out. Charged with providing a musical backdrop for Cacá’s contemporaneous view of Orfeu (shades of the young Antonio Carlos Jobim, hard at work preparing Vinicius’ play in verse for the Rio stage), Caetano decided to spice the new movie up not just with old favorites from The Little Poet’s pen (“all of them works of art”), but with some out-of-the-way innovations of his own.

“My first reaction was to say to Diegues that he shouldn’t compose anything new, because the songs already existed and were so wonderful, that to try new things was ridiculous. But he not only convinced me to be the musical director of the movie, but to compose two new songs. So I created a theme for the samba school, with a slightly lower tempo than the schools usually use because that would be too fast… Then a love song to create something special for this movie, different from the other productions.”

The results, “História do Carnaval Carioca” (“The History of Rio Carnival”) and its companion piece, “O enredo de Orfeu,” loosely translated as “The Script of Orpheus’ Life” and co-written with Brazilian rapper Gabriel o Pensador (“Gabriel the Thinker”), are in the form of rougher-edged samba-funk; while “Sou você” (“I am You”), a soft-grained but anachronistic voice-and-guitar track, is an unabashed throwback to the romantic film ballads of yore.

Caetano Veloso (www.nonesuch.com)

“We are including two [traditional] sambas,” expanded Veloso, “which were not even in the play. Cacá chose ‘Cântico à natureza’ (‘Song to Nature’) and I chose ‘Os cinco bailes da história do Rio’ (‘Five Dances on the History of Rio’). [This] samba-enredo by Dona Ivone Lara is my favorite of all times. I attended the parade of Império Serrano in 1965, and I learned the song in the street.”

In addition, there were several outstanding holdovers from the French-directed Black Orpheus, which consisted of revised versions (more like old wine in new cachaça bottles) of the classics “Manhã de Carnaval” and “A Felicidade,” tossed in with “Se todos fossem iguais a você” and “Eu e o meu amor,” two free-flowing show tunes from the original play that never made it to the screen, before now.

On one level, Caetano’s newly minted “insertions” mirrored his abiding faith in, and deep admiration for, Brazilian street samba and its roots in Afro-Brazilian culture as well as the hip-hop vibes emanating from the once frowned-upon favelas — musically speaking, the poor side of town. On another, more cultivated plane, he felt an obligation to reach across class lines and extend a warm hand to bossa nova, its close cousin, which had its origins in the less economically-deprived areas of Ipanema — on the opposite side of the social track — and for which he expressed a longstanding desire to welcome back into the fold.

Ever mindful of the esteem Camus’ work was still held in most foreign quarters, the singer-songwriter’s plan for incorporating this multiplicity of styles into the revamped Orfeu might actually have undermined his own efforts toward that end. What he got instead was a constant clash of musical and cultural ideas, inappropriately linked, in this author’s mind, to the onscreen battles being waged by evil drug dealers and corrupt police officials, with innocent by-standers (us viewers, perchance?) caught in the middle.

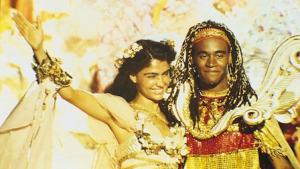

Patricia Franca & Toni Garrido in Orfeu

Sonically, too, there was so much going on one found it trying at times to focus on any one aspect, with the violence and music pumped out at full volume while playing first and second fiddle to the casual love interest between Eurídice and her main man, Orfeu — a mere afterthought in the script and fueled by a noticeable lack of chemistry between the two leads.

Moreover, equating gangsta rap, funk, and hip-hop with some of the more, how shall we put it, lurid story elements (“an ode to the energy, the love and creativity that survive in the midst of violence and misery,” in Diegues’ worldview) was a major faux pas on Veloso’s part. “And if middle class people of today associate poverty with crime,” to repeat the film director’s earlier views, “imagine in the fifties.” Imagine indeed.

In regard to his chameleon-like score, perhaps the sobering thoughts of film scholar Robert Stam can enlighten us as to Caetano’s reasoning behind it all: “[I]t was Black Orpheus, more than any other film, that introduced samba and bossa nova to the world [and whose success] opened the doors for the newborn bossa nova, the ‘modern samba’ that the film’s soundtrack juxtaposes with traditional samba,” born afresh, it would seem, in the Bahian composer’s bold, new experiment to capitalize on his audience’s past acquaintance with these forms, as opposed to its over-reliance on the present-day variety.

Did his gamble payoff in the long run? Judging from the fair-to-middling sales of the movie’s soundtrack, coupled with the lukewarm reception the film itself received around the world-music front, one is forced to give this labor of love a mixed grade at best: certainly an A for effort and an A+ for execution, but only a low to middle C for trying to have it both ways and for incompatibility with the extraordinarily broad range of styles that Brazilian popular music has now grown to encompass.

Toni Garrido (anewtbrasil.blogspot.com)

And certainly, too, for connoisseurs of the Academy Award-winning Black Orpheus and its forerunner, Orfeu da Conceição, this “with-it” adaptation of the ancient Greek myth was a low point in their affection for the smoother, gentler sounds that once sprang from the melody-rich nation of Brazil. (So she finally crossed over into the funk and hip-hop realm. What else was new?) If anything, it proved beyond a reasonable doubt that no matter how hard you try, you can’t go home again to Rio — even with Caetano Veloso as your guide.

(End of Part Six)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes

* By Diegues’ own entirely unscientific methods, Orfeu had earned excellent critical reviews in such cities as Seattle, Chicago, and Los Angeles. But it failed miserably in New York, of all places, the alleged Mecca for all things progressive and avant-garde. This may have led to its not even being nominated for Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards ceremony the following year.