Getting on the Wrong Bus

For all the trash talk surrounding reality-TV programming on the tube, Carlos Diegues’ 1999 version of Orfeu produced one of those “unintended consequences” we so often hear about, but rarely have a chance to participate in or live through ourselves.

What Cacá ultimately showed us, via his media-savvy finale to his film — after their tragic end, our hero and his girlfriend are miraculously “reunited” on the small screen — reflected the horror that thousands of Rio de Janeiro households were forced to witness, on June 12, 2000, courtesy of TV Globo and the other Brazilian networks. Before dozens of live cameras, the notorious Bus 174 incident played itself out in primetime (“an overpowering, for-profit televised show”) by turning a real-life hostage crisis into a soap opera on-demand, a shattering visual climax to a voyeuristic experience worthy of Sophocles himself, let alone one by a Brazilian-born playwright.

Bus 174 (forgottenclassicsofyesteryear.blogspot.com)

Sandro do Nascimento, the homeless (and hapless) hostage-taker, led a traumatic early childhood at best. As a boy, he witnessed the cold-blooded slaying of his mother by knife-wielding bandits, and was one of the few remaining survivors of the infamous Candelária Church massacre of Rio street-kids back in July 1992.

After a life spent in juvenile detention centers and in filthy, overcrowded prison cells, the glue-sniffing 22-year-old was killed — smothered was more like it — in the back of an unmarked van, along with the female passenger he’d held at knife point, by the tactical police S.W.A.T. unit charged with “tactfully” keeping the public order.

* * *

There’s no denying the latest chapter in the cinematic life of poet-musician Orpheus (an avatar for poet-musician Vinicius, no doubt) — dusted off anew “whenever the need was seen to reassert high musical ideals against frivolous entertainment values,” in Richard Taruskin’s prophetic distillation of the same — had proven to be a certified box-office smash, as it barnstormed its record-busting way around Brazil.

In the first month alone, over a million-plus viewers had flocked to movie theaters to see the colorful pageant of a dreadlock-sporting composer named Orfeu (Toni Garrido) pound out a ready-made samba on his trusty laptop; indicating that audiences by the boatload identified with the main character’s struggles to make an honest living for himself, amid the chaos and squalor of Rio’s mountaintop villas.

That he also faced down his ex-boyhood chum, the favela’s brutal drug lord Lucinho (Murilo Benício), in grandiose shoot-‘em-up fashion — Orpheus as action-movie hero — never entered their thoughts.

Notwithstanding its director’s adherence to some of the purer aspects of Brazil’s newly revitalized New Wave — wherein Diegues once extolled the virtues of, in his paraphrased reaffirmation of Glauber’s idée fixe (“An idea in your head and a camera in your hand”) that “Brazilian filmmakers [had] taken their cameras and gone out into the streets, the country, and the beaches in search of the Brazilian people, the peasant, the worker, the fisherman, the slum dweller” — Orfeu pried open the bars to a native-grown cinema of brute force.

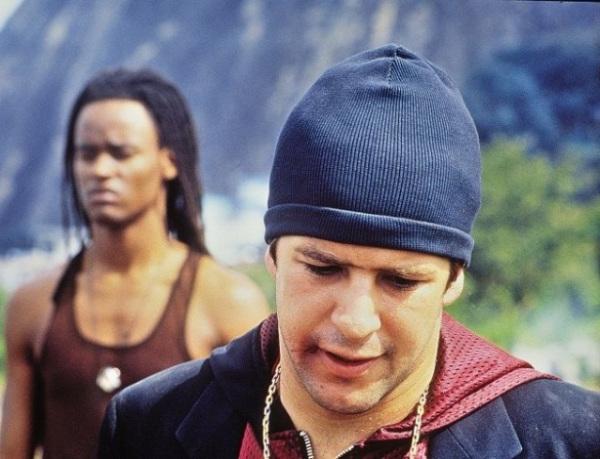

Toni Garrido & Murilo Benicio (fotosnoticias.bol.uol.com.br)

This became the dominant trait of many of the works featured in the period immediately preceding, and immediately after, the highly-rated Central do Brasil (Central Station) made the rounds of movie palaces, chief among them the self-titled Ónibus 174 (Bus 174) documentary, followed by Madame Satã (“Madame Satan”) and the equally harrowing Cidade de Deus (City of God)and Carandiru.

The return of the native film-school aesthetic — one that had barely existed at all when 1959’s Black Orpheus first paraded into view — was marked by a return to the graphically violent nature of urban street life, first touched upon by director Hector Babenco’s chilling portrayal of it in his Pixote: A Lei do Mais Fraco (Pixote: Survival of the Weakest) from 1981.*

Diegues was next in line to take up the challenge of this modern-day movie trend. With typical Wellesian bravado, his unsentimental re-interpretation of Vinicius’ poetic musical tragedy bore the unmistakable strains of social Darwinism; its own incipient “touch of evil” gone awry, infecting everything and everyone, even those we hold most dear — in this instance, the fair-featured Eurídice (Patricia França), accidentally gunned down by the drug lord’s stray bullet.

This sordid re-working, a literal descent into a nightmarish nether-region disturbingly reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno (whose guide, incidentally, was the classical poet Virgil), is as “dark” as anything modern film noir had to offer. In all honesty, there was very little novo about this sort of gritty, blood-and-guts-style cinema, although the film did provide some spectacular aerial footage of Rio, for what they were worth.

A fundamental point, though, remains unclear: was this really what Vinicius had in mind for a screen adaptation of his play? Would he have applauded the Brazilian filmmaker’s “realistic” depiction of his opus? Or, in a more indirect manner, would he have slipped out of the movie theater the way he did back in the waning days of the 1950s? After all, they were fast friends leading up to, and including, the last years of the poet’s life. Before his untimely passing, Diegues had even received the ailing Vinicius’ blessing and consent for a cooperative joint venture that would have displayed his Orfeu da Conceição in the best of all possible lights.

It was only after his sad demise (almost 20 years after, in fact), when legal complications involving the confusing copyright issuances to his songs were formally worked out and laid to rest by Vinicius’ remaining heirs, that Diegues was able to fulfill his life’s ambition and redo the work in the way The Little Poet had intended — or so he would like us to believe.

Toni Garrido & Patricia Franca (robsmovievault.wordpress.com)

To be honest, there were just as many similarities between the two film versions as there were actual differences. What the rank-and-file Brazilian gobbled up, however, others found wanting. It’s now our turn to paraphrase for a moment or two: using Cacá’s own words against him, perhaps the picture offered too “dystopian” a vision of reality for most overseas audiences to identify with. Perhaps prejudice had something to do with it as well.

Perhaps moviegoers abroad simply couldn’t handle the truth about the clear-and-present dangers of carioca slum life; or perhaps there was something else that was missing from the film project — something that brought little, if any, recognition to one of Carlos Diegues’ darkest directorial efforts to date.

(End of Part Four)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes

* Born in Buenos Aires of Jewish refugees (from Russian and Polish extraction, to be exact), Argentine filmmaker Babenco had also been responsible for the ultra-realistic Carandiru from 2004.