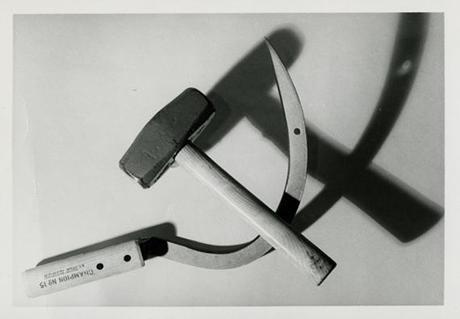

Andy Warhol, Hammer and Sickle, 1976

Zenit’s victory in the Russian league is not a prophetic dream of scientific advancement, but neither it describes, as you would guess from the newspapers, a regression to an inferior degree of football civilization marked, as RIA Novosti put it, by huge character. To understand it, one needs to quietly withdraw from the TV set into a world of pagan orgies, seen both as horrendous saturnalia and sadistic workplace, and telepathic Nazi dogs. Also, it would be crucial to familiarize yourself with mercenaries and magicians, which essentially consists of re-reading your father’s sagas of underworld crime, where an infiltrated Italian gangster turned politician reaches the top of a Fourth Reich organization in 1920s Chicago and dies in exile at Caracas a few years and massacres later. This way, when Zenit wins—as they have done a few times in a row now—you can feel enormous skeletons rustle in the villages, and you might be able to see old names reappear, a New York critic absurdly compare the feat to War and Peace (for lack of better inspiration), and the zones of operation of Zenit’s full-backs resemble the tiny, distorted workings of that old, glorious bureaucratic machinery we still identify with the juxtaposed symbols of the hammer and the sickle.

Luciano Spalletti is a coach of legendary tactical acumen, surrounded by an enduring aura of diminutive, mocking beauty. The stories that have circulated about his first years in Russia rarely concur and often contradict one another. It has been said that he intended to replicate his former Italian exploits (including the famous striker-less formation of Roma and its consequent demotion of Francesco Totti); that he left behind, while in Budapest, a suitcase full of homoerotic poems which would reveal, among other things, that he had audiences with several Uruguayan war criminals; that when he paraded with a naked torso and Franciscan Tau on his chest in the freezing winter it was not to avoid accusations of being a spineless Mediterranean man, but for the love of an aged Peterburgher who just happened to be a widow; that, during a visit to the city flea market, he fell in love with the hat of a KGB general, who was crucified by his own soldiers in 1944; and that, as a consequence of a night of steamy passion with a Romanian waitress, he now carries a red lip-tattoo on his left buttock. His technical work, leaving aside the juvenilia lost in the icy peaks of Switzerland and the apocrypha buried under the Siberian cold, is one torrential and anarchic blend of all the literary genres that make up football: romance, spy novel memoir, history, political pamphlet. In some paragraphs of his Zenit adventure, Spalletti would seem to rely solely on his legendary feminine intuition, while in other plots he would elicit pseudo-scientific speculation about a testicular gland capable of producing exorbitant amounts of testosterone—the only thing considered able to defeat the old locomotives and dynamos of Moscow. ♦