It is clear that if we do not start taking action today, including by carrying out structural reforms, we could end up going into a lengthy period of economic stagnation tomorrow. Our economy is still based primarily on natural resources rather than on manufacturing. Our economic system has changed little in essence. Where does most of our money come from? From oil, gas, metals and other raw materials.

– Vladimir Putin, Annual Address to the Federal Assembly, April 3, 2001

Fifteen years later, the Russian economy envisioned by that progressive speech by Putin in April 2001 seems to be a distant memory. Russia’s economy, and budget, are still largely dependent upon the sale of oil and the majority of Russian industry is still based on extractive industries. The modern vision of Russia in that speech, one deeply embedded into the international system, where property rights are protected by the undiscriminating rule of law, has been replaced by a cynical “managed” system of crony capitalism where profits are skimmed off by insiders while Russia has isolated itself by its actions on the international stage.

Since 2001, record-setting commodity prices have supported increased social benefits, military spending, and infrastructure investments, each of which has supported corruption schemes where insiders profit off of the state’s largess (see the cost of the Sochi Olympics as Exhibit A). High commodity prices also allowed the Russian government to slowly smother individual rights and free speech at home and, largely through key investments in media, buy the country a larger voice in affairs abroad.

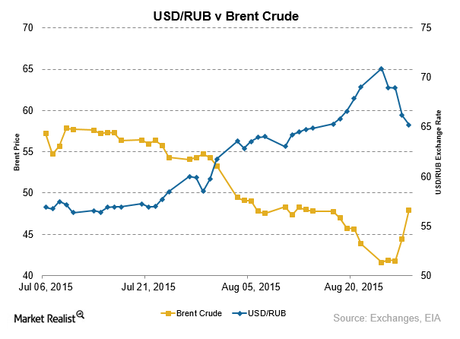

Rather than pulling away from a resource-based economy, Russia’s entire economy appears to now be moving in near perfect correlation with energy prices (see chart below).

According to a recent Bloomberg article, Russia’s 2016 budget was initially planned around oil prices averaging $50 a barrel, resulting in a deficit of 3 percent of GDP. However, given the much lower price of oil recently, Russia’s Finance Minister has revealed that an additional savings of $18.9 billion is needed to avoid a shortfall of over 6 percent of GDP. While prices have now rebounded to approximately $45 a barrel (as of May 3, 2016) the U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts an average price of $34.73 for 2016, which if accurate would likely result in negative economic growth and high inflation – a classic cycle of “stagflation,” which is difficult to pull out from without some external factor.

Russian authorities seem to be rubbing salt in their economic wounds through a recent order requiring state-owned enterprises to increase dividends. The April 18 order, signed by Dmitry Medvedev, applies to eight state-owned companies and mandates that they pay 50 percent of their net profits as dividends. The order stipulates that net profit may be calculated following Russian Accounting Standards or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), but the companies must pay a dividend in accordance with the higher of the two values. While market reaction to the move has been generally positive — shareholders do like dividends — it begs the question if Russia is robbing Peter to pay Paul. These companies are in industries like oil and mining that require heavy investment in infrastructure and upkeep of equipment, and with pressure from the state to deliver higher dividends the long-term ability of these companies to maintain output may be compromised.

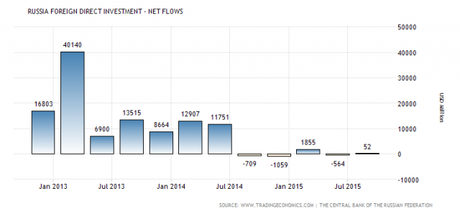

If all of this news was not bad enough, the Kremlin, though a series of foreign engagements with its neighbors, has landed many key individuals and companies on a variety of U.S. and European sanctions lists. These sanctions have, in turn, effectively closed off the Russian economy from foreign debt markets after warnings from the U.S. Treasury that running a bond offering from Russia may be violating sanctions. Sanctions have also hurt foreign direct investment in Russia, which tumbled from approximately $12 billion per quarter prior to sanctions to approximately $52 million in the last quarter for which data was available. Capital outflow from Russia was also forecast by the World Bank to total $113 billion in 2015 and $82 billion in 2016.

The final question is whether any of this will affect the performance of Vladimir Putin’s party at the parliamentary election in September. Judging by fact that few ordinary Russians connect Russia’s ongoing economic problems with the party in charge it would appear that the nation’s current mismanagement will continue into the indefinite future.

It will be interesting to see if Russian’s attitudes towards the economic management of their country will have changed by the 2018 presidential election cycle. Based on breaking periods of stagflation in the United States, which were only ended by the start of World War 2 and the interest rate “shock therapy” of Paul Volcker combined with the IT revolution, the pattern of economic and political malaise in Russia will likely continue past the parliamentary election and into the presidential election cycle, at a minimum.

Eric Hontz is a Program Officer for Eurasia at CIPE.