Your best against our best: it's the sacred principle on which all international team sports are built. And yet even a league as enmeshed in tribal identity as the Six Nations has drifted from these moorings. Take last weekend's Calcutta Cup, a match electrified by Scotland's Duhan van der Merwe, whose name hardly suggests a rugged clan from the Cairngorms. Not that the problem can ever be reduced to a single player. Of the 39-man squad that Gregor Townsend selected to wear Scots blue this year, an astonishing 23 were born elsewhere.

The fluidity of nationality is constantly lurking in the background during this tournament. I remember speaking to Mouritz Botha in 2012, who spent all his formative years in South Africa, having completed the degree for England thanks to the three-year residency rule. "You develop pride and passion for your country over time," he explained. But is this enough? Can this fast track to unwavering national loyalty ever be more, in sporting terms, than an alliance of convenience?

Ollie Hassell-Collins provides an instructive example. The memory of the two Six Nations caps he earned for England last year is still fresh in his mind, as he spoke of how long he had dreamed of donning the red rose. A year later, with his career at Test level having hit the buffers, he reveals to The Telegraph that he is equally enamored by the idea of representing Wales. He has a Welsh grandmother, you see. And that, assuming he doesn't make a surprise impression in England's ranks in the meantime, will be all he needs to pull off Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau (Land of My Fathers) in 2026.

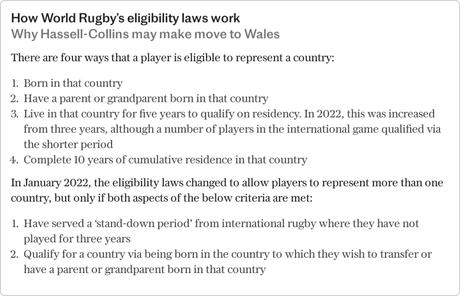

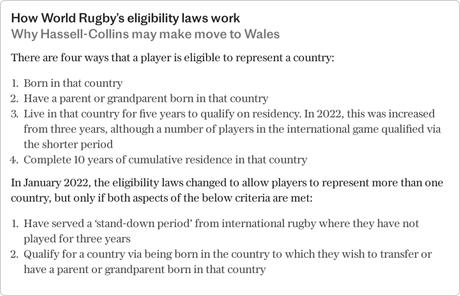

The situation quickly veers into the realm of absurdity. Hassell-Collins, we must emphasize, is not proposing anything that violates the rules. World Rugby's Regulation Eight clarifies that his qualifications are assured by having a grandparent born in the same country, and that a change of national allegiance is possible after a period of 36 months. But we can certainly drop any pretense that his ruse is a passion project. Here's a player who, as it stands, isn't even considered good enough for the England A team, but gets to keep the Wales option on the table as a handy option.

The story continues

It begs the question of what we are looking at here. Eddie Butler's video montages would make the Six Nations famous in terms of centuries of battles and bloodlines, but today's on-field reality isn't always so poetic. Look at Nick Tompkins, the center who was born in Sidcup to English parents, went to school in Bromley and went to England with the under-18s, under-20s and the Saxons. Now, after all that upbringing under the English system, he's competing for Wales, for no better reason than that he has a grandmother who was born in Wrexham.

The Tompkins case provides an argument for eligibility for a test based on a stronger family bond or a longer period of residence. After all, this is a controversy that extends far beyond Wales. Immanuel Feyi-Waboso, a bright international wing prospect at 21, was born and raised in Cardiff but opted to play for England via the tried-and-tested grandma route. You can imagine that Neil Jenkins spoke for many when the former fly-half was quoted by Warren Gatland as saying: "If he doesn't want to play for Wales he can leave." A young man growing up in the shadow of the Principality Stadium, but still defecting to the implacable enemy? It would once have been unthinkable.

Today it's almost time de rigueur. Entry requirements have become so lax that you're left wondering whether the Scottish team that just beat England can even be called authentically Scottish, given that the majority were not born there. In addition, research by Paul Tait, an expert on this subject Rugby news from America, shows how 22 of the 23 imported players cannot even be called homegrown. Alec Hepburn and Ben White previously wore the colors of England, while Jack Dempsey played for Australia. Ben Healy and Sione Tuipulotu were recruited from abroad specifically with the aim of playing for Scotland, with Healy only moving from Ireland at the age of 23 and Tuipolutu not arriving from Australia until the age of 24.

This seems impossibly late for anyone to insist that they have acquired an undying devotion to their adopted country. On the contrary, it smacks of countries carefully using a loose system to their advantage. And Scotland, within the Six Nations, is the runaway leader on this front. Their 23 non-English born players may be a staggering number, but it's not even their record. Two years ago there were 27. Look how this compares to their rivals: England have six foreign-born players, Wales five, Ireland eight, France six and Italy eight.

External talent stifles domestic development

It would have taken a brave soul to point out this glaring discrepancy to the Scotland fans in Edinburgh last Saturday evening. Everywhere you looked outside Murrayfield the bagpipes were blaring and the Tennent's were flowing. If a fourth Calcutta Cup on the horizon - a series unparalleled for 128 years - wasn't worth celebrating, what is? However, there is a legitimate debate to be had over the extent to which the Test team's dependence on external talent is strangling domestic development. When Scotland Under-20 played Ireland last year they were beaten 82-7.

Even the Irish, heralded as the gold standard in everything they touch, know what it means to exploit rugby's vague definitions of nationhood. Bundee Aki, James Lowe and Jamison Gibson-Park are three players who have supported Ireland's transformation into Grand Slam winners and, for a time, world number 1. But they were all integrated into New Zealand's professional rugby system and focused on moving to Ireland well into adulthood so they could comply with residency rules. Lowe is about as Irish as McDonald's Shamrock Shake, coming to the country when he was 25 and playing for the Maori All Blacks against the British and Irish Lions.

How much does all this matter? There can be no doubt about Lowe's popularity in Ireland, in light of the wing's stellar performances, coupled with the frequent protests that his head and his heart are in the Emerald Isle. Very endearing of course - as was his father's decision to watch one of his victories in full Irish kit and a Leinster hat. But in a technical sense it does not detract from his Irish credentials. Here is a player who, realizing in his mid-20s that he would never achieve his All Black dreams, traded Nelson for Dublin with the assurance that he would be wearing green three years later. The decision, while an emphatic success for his CV, casts an unflattering reflection on the romanticism of Test rugby.

On paper, enabling all these nationality shifts should be beneficial for the game's emerging nations. The problem is that many players jump from one Tier One country to another. This is a practice expressly prohibited in rugby league, but it is widespread in the union. Just as Lowe reinvented himself in Ireland out of frustration that his progress in New Zealand had stalled, Hassell-Collins' plans to swap England for Wales are purely pragmatic, bordering on opportunistic. The top tier of the game seems more like a self-perpetuating cabal than ever.

'It is strange that these patterns have not yet sparked a more urgent discussion in rugby. In football, many get goosebumps at the mere thought of choosing a successor to Gareth Southgate who is not English. But during the Calcutta Cup, the fact that man-of-the-match Van der Merwe honed his craft in South Africa, and not Scotland, went almost without mention. Your best versus our best? It increasingly appears that the Six Nations are less concerned with blood ties than with gun leasing.