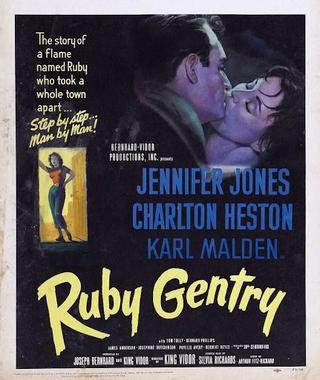

Incompatibility, or the absence of harmony, is what Ruby Gentry (1952) is all about. It's a tale of love and ambition, and the friction generated by attempting to marry those two emotional opponents. Underpinning all that is the downbeat assertion that it is futile for one to try to escape the bonds of the past, that the future has already been mapped by circumstance or one's forebears, or perhaps some unseen guiding hand. This fatalistic view, one approaching the idea of predestination, tilts the movie in the direction of film noir; I think it is deserving of the noir label although I do acknowledge that there are those who will claim it is debatable whether it really belongs in that nebulous category.

Dr Saul Manfred (Barney Phillips) is the man from whose point of view the story is seen. He's our narrator, a kind of everyman guide taking us through the varied and tangled relationships at the heart of the affair rather than one of those pompously stentorian "voices of authority" that sometimes lecture the audience at the beginning of a film noir. His is a much more thoughtful and sensitive description of events and people, a reflection of the character himself and also of the personal stake he had in its development, at least at the start. He tells of Ruby (Jennifer Jones), and it's one of those classic parables detailing the rise and fall not only of the title character but of all those who were part of her life, and indeed one might even say of the rise and fall of the stuffy and socially suffocating community they all inhabit. Ruby is introduced as a swampland tomboy, an impoverished temptress in tight sweaters and torn jeans, as skillful with a rifle as she is careless with the hearts she captures. Simultaneously skittish and coquettish, she has spent time fostered in the well-to-do household of local big shot Jim Gentry (Karl Malden) and it's whispered among the more mean-spirited in town that she has acquired ideas above her station. This is clear from her romance with Boake Tackman (Charlton Heston), a returning jock from a patrician background and a head full of big plans. The rigid social order is disapproving and Tackman hasn't the moral courage to rise above this, so Ruby is drawn back into the world of the recently widowed Jim Gentry. Thus a complex web of ambition and desire is spun around a set of people who all think they know what they want but have no clear idea of how to get it, or to hold onto what they do manage to grab.

King Vidor's direction (working from a script by Silvia Richards) is beautifully controlled, pacy and rarely extravagant yet lush in its depiction of the steamy swamp where the climactic scene is played out and also in the richly detailed interiors, especially the house occupied by Ruby and her family. He uses space well to convey mood, the joyous and liberating race along the beach and through the surf in Tackman's car perfectly captures the early exuberance of Ruby and her love, and then the cramped room which she shares with Jim and the doctor for the failed party after her marriage encapsulates the narrow and restrictive world she finds herself in. In the creation and presentation of these varied moods Russell Harlan's cinematography is all one could ask for and no less than one would expect from such an artist in the manipulation of light. Ultimately, the movie works as a condemnation of unfettered ambition, where each of the main characters systematically destroys everything they care for in the pursuit of the unattainable. It is this, alongside the sour judgemental snobbery of a blinkered society, which stymies the only pure feelings on show - love is either thwarted or left unfulfilled and atrophied.

Jennifer Jones as the title character does succeed in drawing in the viewer, her allure is clear from her first appearance and the reunion with Heston on the porch in the dark and by torchlight gives a foretaste of the tumultuous nature of their relationship. Her efforts to fuse her love and her hunger to climb the social ladder is apparent from early on and the slow realization that she can only achieve the latter at the expense of the former is painful to see but convincingly portrayed by Jones. In the final analysis, hers is not an attractive character, the vindictiveness (though understandable) adds coldness and her attempts time and again to net Heston detract from her somewhat.

That latter aspect is amplified when it comes to the marriage to Malden's besotted millionaire. His motives are the most straightforward and honest of the lead trio and he consequently earns a good deal of sympathy. There is a terrifically affecting moment when he catches his wife out in a foolish betrayal and you can see not only his world crumbling before his eyes but his assessment of himself as a man undergoing a reevaluation as he gazes in frank despondence into the mirror behind the bar of the country club. Heston simply oozes machismo, that powerful screen presence clear from even this relatively early stage in his career. For all the swaggering bravado though his Boake Tackman is a moral coward, a "back-door man" hiding behind his family's position and reputation. Also deserving of mention is some fine work from Tom Tully, Barney Phillips and, in a disturbingly fanatical turn as the scripture-quoting brother, James Anderson.

Ruby Gentry has had a Blu-ray release in the US from Kino and there are a range of DVDs out there as well. I still have my old UK disc put out by Fremantle many years ago and it presents the movie most satisfactorily, although there are no supplements whatsoever offered. The movie has a strong emotional hook and Vidor's assured direction, as well as Harlan's cinematography and Heinz Roemheld's score, combines effectively with some excellent performances. This may not be a picture you come away from with a particularly positive glow but it does have some depth and the final image, and message, may not be quite as downbeat as it first appears.