"Consider the diamond itself for instance. Carbon, soot, chemically speaking. And yet the hardest of all matters. So hard, in fact, that whatever it touches must suffer: glass, steel, the human soul."

Peter Lorre uses that line, or a variation thereof, something like three times throughout Rope of Sand (1949). It's not a bad line and has an air of wistfulness about it, and it's tempting to wonder whether the filmmakers were hoping that repetition might encapsulate the spirit of the movie. In a way it does, but probably not as originally envisaged. In essence, Rope of Sand is a simple story, one incorporating revenge, justice and a treasure hunt. Yet for all its simplicity, it feels somewhat repetitious, stretching its material more than is necessary and losing some of the inherent tautness in the process.

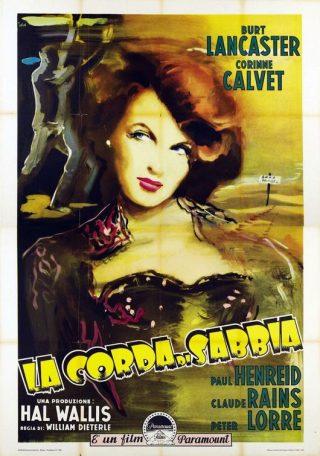

In brief, the plot revolves around Mike Davis (Burt Lancaster), a disgraced hunter who has fallen foul of the mining authorities after stumbling through (I presume, although it's never explicitly referred to as such) the Namib desert in pursuit of a client who recklessly felt he could sneak out some diamonds. The result is the death of the client as well as beating and torture for Davis, supplemented by the loss of his license. That ought to be enough to ensure any man would give the place a wide berth in future, but Davis is driven in true noir style by both a thirst for revenge and some sort of justice or recompense - he doesn't appear certain himself which one holds the strongest allure. Up against him is the local commandant, the sadistic Vogel (Paul Henreid), and his debonair boss Martingale (Claude Rains). The latter wants to lay his hands on the diamonds Davis left behind just as much as the aggrieved hunter does. To that end he flies in a Frenchwoman of questionable reputation (Corinne Calvet) with the aim of coaxing the location from Davis, and then delights in the added bonus of seeing the new arrival add another layer to the antagonism between Vogel and Davis.

Walter Doniger's script contains a fair bit of toing and froing, plans made and dropped, schemes attempted and foiled, and retribution handed out. There are dark mutterings amid exotic surroundings, interspersed with a smattering of witticisms as dry and abrasive as the South African sand. Past events are alluded to over hard liquor and a haze of cigarette smoke, then rather unnecessarily clarified via a flashback sequence that serves to simply slow everything down. And all the while the tone is shifting in tandem with the dunes of the surrounding wasteland, louche charm rubbing shoulders uncomfortably with instances of truly grim brutality.

On the other hand, these Hal Wallis productions tend to have a very grand look, a real cinematic sheen that is hard to resist. William Dieterle's mise-en-scène and Charles Lang's wonderful lighting combine to present some genuinely sumptuous shots and on occasion it approaches expressionism - the silhouetted figure atop a dune, the torture of Lancaster. Visually, the whole production is quite splendid. As for Franz Waxman's score, I again found portions of it jarred and almost swallowed up the action on screen instead of complementing and supporting it.

Burt Lancaster is said to have disliked the movie intensely but his work on screen reflects none of that. It's yet another variation on his, by that stage, patented studies in tough vulnerability and the type of thing he could practically sleepwalk through. Maybe it wasn't much of a stretch for him dramatically but he turned in a credible piece of work all the same. Paul Henreid 's interpretation of an irredeemable sadist is powerful and intimidating, saved from becoming totally one-dimensional by the actor's ability to hint at an awareness of his own failings. Claude Rains is all silken malice, a puppeteer whose viciousness only appears more palatable than that of Henreid due to the sheen of elegance and sophistication he wraps it up in. The only woman in the story is Corinne Calvet, hired by Rains to act as a siren and finding herself gradully falling victim to the subterfuge and betrayals. Sam Jaffe's alcoholic medic is underused and Peter Lorre as a lowlife fixer going by the glorious name of Toady drifts in and out of proceedings like some sweat-stained Falstaff.

Olive Films released Rope of Sand on both DVD and Blu-ray in the US but I'm not sure about availability elsewhere. It sports a terrific cast and Dieterle's visual nous is never in question. I'd say it is sporadically entertaining, but the script allows the plot to drift too much in places and the tone lurches a little too freely - the smart dialogue and the harsh physical violence form an uneasy mix with this viewer.

That brings me to the end of this brief exploration of the cinema of William Dieterle which I have undertaken over the course of this month. I did toy with the idea of keeping it going a little longer but I have a hunch a triple bill such as this is sufficient for the present as too much of a good thing can be counterproductive. Nevertheless, I will certainly return to the director's work as it represents a rich vein for movie fans.