Roadside Biology Introduction

The roadside biology project begins today. It’s been 25 years since I read Halka Chronic’s Roadside Geology of Arizona and imagined something similar for biology. Spurred by our global climate emergency, and knowing that soil, natural vegetation, and wild animals are disappearing at an accelerating rate, I can delay no longer.

Sonoran Desert Vegetation beside Interstate Highway 17.

The project goal is a travellers’ guide to roadside vegetation. Vegetation is the most visible element of natural ecosystems. Moreover, vegetation is the principal source of food, fiber, and shelter for animals including humans. Of course, there would be no vegetation without soil. Soil profiles, the layers, colors, and textures that show the climate and geologic conditions controlling soil formation are sometimes visible in road cuts and steep-sided gullies and arroyos.

Learning the names of different groupings of plants is necessary for thinking and communicating about vegetation. Vegetation and soil develop over thousands of years. Within the natural limits set by latitude, longitude, elevation, slope angle, and bedrock, plant species come and go in a slow winnowing process. Left undisturbed, species groups form that are best fit to flourish in the environment of each place. However, human building, farming, and toxic wastes can change vegetation and soil within one or a few years. These changes can be so drastic that they are immediately detectable, but in many instances the changes are subtle. Historical records and protected vegetation sites show what the vegetation was before human changes began (Kuchler 1964, Turner et al. 2003 [(see references at the end)]. My master’s thesis, doctoral dissertation, and post-graduate research dealt with human-caused vegetation changes, and as we go along, I will add what I learned to published research by other scientists to explain changes in the roadside scenery.

Biological Soil Crusts

Invasive Plants

Previous Research

Vegetation Ecology & Classification

Vegetation is numerous plant species each varying in size, shape, color, and abundance. One or a few prominent species give character to the vegetation. We use these species in discussions of regional vegetation such as ponderosa pine forest, cottonwood-willow riparian vegetation, and saguaro cactus shrubland, These species, and many others that are not so visible, are often tolerant of a range of climates and soils. But some plants are found only on particular soils, in the presence or absence of certain other species, or in certain topographic positions. Vegetation ecologists (Mueller-Dombois and Ellenberg 1974) learn to recognize these diagnostic species and use them to classify the smallest groups of species that consistently grow together.

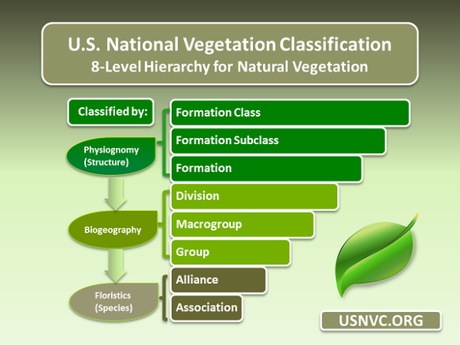

Recurring groups of species fit into an eight level hierarchical classification. Plant shapes define the highest levels, location defines the intermediate levels, and species define the lowest level.

- CEGL001340 Acacia greggii – Parkinsonia microphylla Shrubland Association

- CEGL001375 Parkinsonia microphylla – Larrea tridentata Shrubland Association

- CEGL001389 Carnegiea gigantea / Prosopis velutina Wooded Shrubland Association

A3283 Simmondsia chinensis – Canotia holacantha – Eriogonum fasciculatum Desert Scrub Alliance

- CEGL000953 Ambrosia deltoidea / Simmondsia chinensis Shrubland Association

- CEGL000983 Simmondsia chinensis – Parkinsonia microphylla Shrubland Association

- CEGL005296 Canotia holacantha Grand Canyon Shrubland Association

- CEGL003065 Opuntia bigelovii Shrubland Association

A3277 Larrea tridentata – Ambrosia dumosa Bajada & Valley Desert Scrub Alliance

- CEGL000956 Ambrosia dumosa – Larrea tridentata var. tridentata Dwarf-shrubland Association

- CEGL001261 Larrea tridentata Monotype Shrubland CEGL002954 Larrea tridentata – Ambrosia dumosa Shrubland Association

- CEGL005136 Larrea tridentata – Ambrosia dumosa – Fouquieria splendens Shrubland Association

- CEGL005137 Larrea tridentata – Ambrosia dumosa – Krameria (erecta, grayi) Shrubland Association

- CEGL001268 Larrea tridentata – Ephedra nevadensis Shrubland CEGL001273 Larrea tridentata – Opuntia basilaris – Fouquieria splendens Shrubland Association

- CEGL002717 Larrea tridentata – Coleogyne ramosissima Shrubland Association

- CEGL004452 Fouquieria splendens Shrubland Association

- CEGL005081 Encelia resinifera Shrubland Association

- CEGL005118 Fouquieria splendens / Encelia (farinosa, resinifera) Shrubland Association

- CEGL005138 Larrea tridentata – Encelia farinosa – Fouquieria splendens Shrubland Association

- CEGL005145 Larrea tridentata Shrubland Association

- CEGL005074 Ambrosia dumosa Dwarf-shrubland Association

- CEGL000954 Ambrosia dumosa – Ephedra (fasciculata, nevadensis) Dwarf-shrubland Association

- CEGL001252 Encelia farinosa – Ephedra (fasciculata, nevadensis) Shrubland Association

- CEGL002955 Larrea tridentata – Encelia farinosa Shrubland Association

- CEGL005061 Ambrosia dumosa – Encelia farinosa Dwarf-shrubland Association

- CEGL000955 Ambrosia dumosa / Pleuraphis rigida Dwarf-shrubland Association

- CEGL003051 Pleuraphis rigida Grassland Association

- CEGL001962 Eriogonum deserticola Sand Dune Sparse Vegetation Association

- CEGL001264 Larrea tridentata – Atriplex hymenelytra Shrubland Association

- CEGL001317 Atriplex hymenelytra Shrubland Association

- CEGL001164 Chilopsis linearis Shrubland Association

- CEGL002701 Psorothamnus spinosus Shrubland Association

- CEGL002706 Ericameria paniculata Desert Wash Shrubland Association

- CEGL002357 Fallugia paradoxa Colorado Plateau Desert Wash Shrubland Association

- CEGL005298 Fallugia paradoxa Grand Canyon Desert Wash Shrubland Association

- CEGL005391 Bebbia juncea Shrubland Association

- CEGL005392 Brickellia longifolia Shrubland Association

- CEGL005398 Hymenoclea salsola Wash Shrubland Association

- CEGL005331 Calliandra eriophylla / Eragrostis lehmanniana Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005332 Eragrostis lehmanniana Ruderal Grassland Association

- CEGL005333 Eragrostis lehmanniana Ruderal Shrub Grassland Association

- CEGL005337 Panicum antidotale Ruderal Grassland Association

- CEGL005463 Cynodon dactylon Western Ruderal Grassland

- CEGL001384 Prosopis glandulosa / Mixed Grasses Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005343 Prosopis velutina / Eragrostis lehmanniana Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005344 Prosopis velutina / Atriplex canescens / Mixed Grasses Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005345 Prosopis velutina / Calliandra eriophylla Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005346 Prosopis velutina / Mimosa dysocarpa Ruderal Shrubland Association

- CEGL005347 Prosopis velutina Ruderal Foothill Shrubland Association

- CEGL005348 Prosopis velutina / Mixed Grasses Ruderal Shrubland Association

Roadside Biology Methods

The roadside biology guide will transform roadside colors and shapes into species and plant communities. For highway segments chosen for convenient starting and ending points, I will prepare maps, photographs, diagrams, and narrative descriptions of dominant plant species, and I will include lists of plants, animals, and soils.

Beginning – April 7, 2016

Organ Pipe Cactus, H.E. Price

The project begins at the Arizona-Mexico border on Hwy 85. The highway runs north 25 miles through Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. The 330,000 acre Monument is an ideal beginning. Created in 1937 by presidential proclamation, the United Nations declared the monument an International Biosphere Reserve in 1976. In 1978, Congress designated nearly 95% of monument lands as wilderness. The monument has served as a laboratory for scientific research and environmental monitoring since the early 1980s.

Base Maps and Publications

The U. S. Geological Survey GAP program produced the primary base map for this project. I will also use narratives, maps, and photographs of Arizona vegetation, soils, and wildlife by Brown (1982), Brown and Lowe (1980), Hendricks (1985), Lowe (1964), Rogers, Turner (1974a and 1974b), Turner et al. (2003), and others.

Roadside Biology References

Brown, D. E. 1982. Biotic communities of the American Southwest–United States and Mexico. Desert Plants 4: 3-341.

Brown, D. E. and C. H. Lowe. 1980. Biotic communities of the Southwest: Map. U. S. Forest Service General Technical Report RM 78.

Felger, R. S. and B. Broyles, eds. 2007. Dry borders: Great natural reserves of the Sonoran Desert. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah. 799 p.

Hendricks, D. 1985. Arizona soils. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. 244 p + map.

Küchler, A. W. 1964. Potential natural vegetation conterminous United States: Map

Lowe, C. H., ed. 1964. The vertebrates of Arizona: Landscapes and habitats, fishes, amphibians and reptiles, birds, mammals. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. 270 p.

Mueller-Dombois, D. and H. Ellenberg. 1974. Amins and Methods of Vegetation Ecology. John Wiley & Sons, New York. 547 p.

Rogers, G. F. 1974. Vegetation change in relation to groundwater depletion and climatic fluctuation in south-central Arizona: 1868-1974. Master’s thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona. 91 pp.

Turner, R. M. 1974a. Map showing vegetation of the Phoenix area, Arizona. U. S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigation. Map I-845-I.

Turner, R. M. 1974b. Map showing vegetation of the Tucson area, Arizona. U. S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigation. Map I-844-H.

Turner, R. M., R. H. Webb, J. E. Bowers, and J. R. Hastings. 2003. The changing mile revisited: An ecological study of vegetation change with time in the lower mile of an arid and semiarid region. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. 334 p.

Webb, R. H., S. A. Leake, and R. M. Turner. 2007. The Ribbon of Green: Change in riparian vegetation in the Southwestern United States. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona. 463 p.