The mental images that most Americans have of the American Civil War involve the scenes of major land battles -- Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg. Armies marched dozens of miles, prepared encampments and defensive works, and either attacked the enemy in its own prepared defenses or awaited contact with the enemy. The picture is Napoleonic: an army marching across terrain to fight other slow-moving armies.

It is therefore highly interesting to realize that naval warfare on rivers -- especially the Mississippi River -- played a key role in the success of Union forces in 1862-1865, and that armored steamships were critical to victory. To an extent that is now hard to imagine, with modern transportation networks including dense highway networks, as well as air and rail systems, how important control and navigation of the Mississippi River was to both Union and Confederate war fighting. General Ulysses S. Grant's strategy for bringing the war to the South was dependent on the objective of gaining control of the Mississippi River; and the river was a key component in the movements of troops, supplies, and field headquarters around the contested territories.

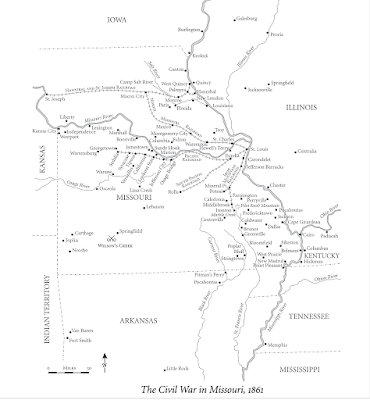

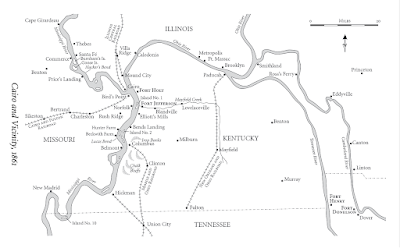

maps: Feis, Grant's Secret Service, p. 12

maps: Feis, Grant's Secret Service, p. 12

The reason for this importance of control of the Mississippi has to do with speed of deployment and logistics. (There was also a major economic consideration: if the South could close the Mississippi, it would cause great hardship for the Northern population.) But consider the logistics and speed issues. The speed of advance of an army on the march through water-logged terrain with poor roads -- conditions that obtained during much of Grant's campaign in the west -- was miniscule in comparison to a steamship moving unhindered several hundred miles along the river. As a rough estimate, it would take an army 21 days to march from Cairo, Illinois to Vicksburg, Tennessee, whereas it would take a steam-powered riverboat about three days to travel the same distance. And steamships could carry all the materiel required for the campaign. (Travel up-river the same distance would take longer.) Maintaining a supply line for the mountains of food, horse fodder, ammunition, replacement equipment, and evacuation of the wounded required by an army in the field depended on heavy transport -- by rail or river boat. Rail transport was substantially faster than riverboat transport -- the average rail speed unhindered by sabotage of tracks, etc. was 25 mph, compared to 5-7 mph for river transport. So rail transport was preferable. However, controlling and maintaining rail networks in hostile territory was extremely difficult, since local sympathizers could sabotage tracks and bridges in dozens of remote places. As a result, naval operations were a key part of the Union's war fighting in the west of the country. The Mississippi River represented the great north-south highway along which the war in the west was fought.

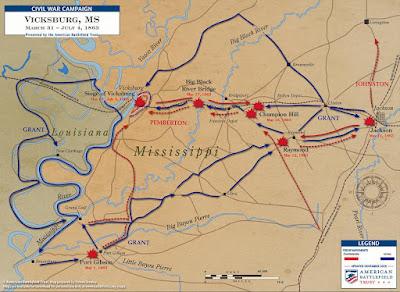

The strategic importance of strong fortifications with heavy guns at locations along the river permitting control of traffic was plain to all sides; so major battles developed involving attempts to seize fortified places like Vicksburg, Mississippi. Grant's persistent effort to besiege and occupy Vicksburg was a mark of his strength as a general, and the eventual success of his plans represented a turning point in the Civil War. But key to success at Vicksburg (and Fort Henry a year earlier) was the availability of a growing force of river warships, from lightly armed gunboats to ironclad and timber-clad steamships with heavy armaments capable of assaulting land-based fortifications. And almost none of this range of river craft existed before the onset of war. The use armored river steamboats of the Civil War thus represented a major technological shift in warfare -- perhaps as dramatic in 1861 as high-precision artillery has been in Ukraine in 2022.

The high end of these armored vessels were the City-class gunboats ("turtles"). These were ironclad vessels designed for service in rivers rather than open seas. They had shallow draft of six feet, were armed with thirteen guns, and could cruise at eight knots. Seven boats were delivered by January, 1862, and they played a significant role in major battles along the Mississippi River, including Vicksburg. These ships included the USS Baron DeKalb, Cairo, Carondelet, Cincinnati, Louisville, Mound City, and Pittsburgh.

Complementing these ironclads was a larger group of wooden vessels that also played a major role in river warfare during the Civil War. Angus Konstam's book Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War 1861-65 provides a review of the rapid development of armored wooden gunboats as the war in the west heated up. These craft needed to be shallow-draft, and they needed to be maneuverable enough to manage the twisting courses of the midwestern rivers. They were steam-powered and relatively slow, but provided both heavy mobile armaments and heavy transport for the strategic thrusts of the army. They could be used to transport troops, and they therefore permitted rapid shifts in the location of land-based attacks.

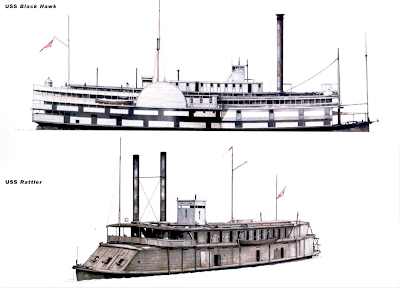

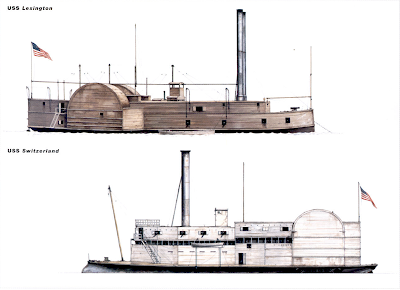

A rapid effort at ship-building and conversion ensued by both Confederate and Union militaries after the outbreak of war, and within a year each side had a number of river-based warships. The earliest heavy gunboats in the Union arsenal were converted commercial vessels -- the Conestoga (572 tons), the Lexington (362 tons), and the Tyler (420 tons), launched in summer 1861 and shielded with thick timber. In addition to the heavy gunboats, the armies also needed a larger number of smaller river gunboats (150-250 tons) that could be used to patrol the river and serve as transport up and down the river (9). The flagship of the river navy, also converted from commercial use, was the USS Black Hawk (902 tons). (All these data are drawn from Konstam's table of ships operated by both sides.) These wooden river warships were immediately thrown into the struggle.

What emerged was a campaign involving the attack on these Confederate naval and riverside defenses by two fleets: One descending the river from Cairo, Illinois, and the other (after the fall of New Orleans in April 1862) working its way up from the Gulf of Mexico. After a brilliantly executed attack on Fort Henry and Fort Donelson [by forces commanded by Grant] on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, Union naval forces in the upper Mississippi faced a series of imposing fortifications. (Konstam, 5)

Fortifications and heavy guns at Vicksburg were the most significant of these Confederate capabilities on the Mississippi River, and it took great fortitude for army and naval forces to eventually take Vicksburg in July 1863. This represented a major turning point in the Civil War.

What is particularly interesting to me about this quick exposure to river warfare in the 1860s is the fact that there were several tempos of operations in the Civil War -- the movements of armies at 15-20 miles per day, the movements of troops, officers, and materiel by steamship at perhaps 100 miles per day and by rail when available at 400 miles per day, and the transmission of messages at Internet speed by telegraph. The faster pace of steamboat and rail warfare fundamentally changed the challenges and opportunities confronting the generals. It is plain, then, that the American Civil War was a high-tech war, with innovations and adaptations introduced into war fighting in real time. (Even the evolution of heavy weaponry and ammunition moved forward quickly during the five years of fighting.) Here again, the similarity to the Ukraine war is striking.

(Here is an interesting photo essay on the evolution of Civil War gunboats; link.)