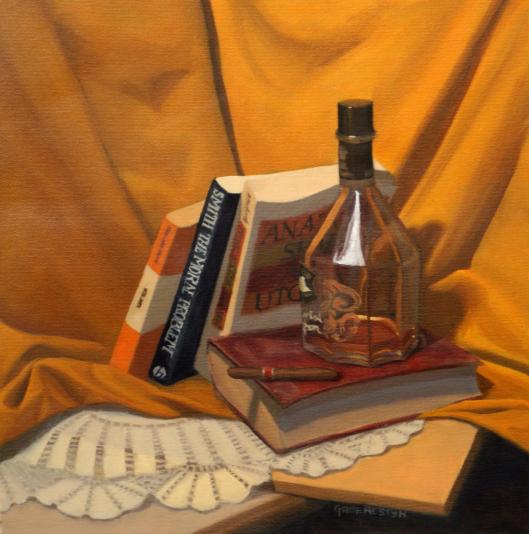

Nausea © Samantha Groenestyn

A government employee once said to me, upon learning of my aspirations to make a career of art, ‘Oh, so you’ll be getting used to a life of applying for and living off government grants.’ He said it so off-hand, as if this were a completely unremarkable way to earn one’s living. I had never considered applying for a grant, and didn’t know this was really considered a viable lifestyle choice.

In fact, I was disturbed that anyone could consider it unremarkable that I could leave my livelihood to chance. That I could work full time, ever more skilled, and merely hope to get awarded a prize, or a share thereof, rather than simply be paid what I’d earned. I was utterly disgusted that as a painter, producing good work might not be enough—I must also grovel to the government, who pays its staff $50 000 to $100 000 (perhaps more) to agonise for days over the specifics of selection criteria in grant applications for a share in a few thousand dollars. After a more senior government colleague and I spent a week on one such application and our department awarded us $3000 between us for the effort, we finally awarded the measly $3000 grant to some struggling community-led organisation with a whole swag of conditions. I spent my share on books and beer. The thing about getting paid for your work is, you spend your money as you please. The thing about getting a grant is, the government wants a say. And it’s far less money than a regular wage. Even some of the best awards are less than working part time on minimum wage for a year—and at least part time work is more or less guaranteed.

‘But how can I possibly choose just one?’ – Nationalbibliothek, Wien

One likes to think a good government would support the arts; that it would conceive of its cities as shining cultural milieus, filled with clever and productive citizens in a whole variety of fields. It doesn’t have to be out of the ordinary to go to the ballet of an evening after work, nor does it have to be out of the reach of even the unemployed. Vienna certainly worries after its unemployed folk, and ensures their entry to museums, galleries and operas should they desire it, so as not to forcibly disconnect them from their city’s proud cultural heritage. Hell, you can bring your fold-up chair and sit and watch the opera in the square on a big screen, live, free, of a summer evening.

Wiener Staatsoper

But the idea that the government has a hand in how art is conceived, produced and viewed is a little bit worrying. There is something undeniably prescriptive in the grants offered by the Australian government, which demand strict budgets, stipulate that projects must be interdisciplinary, and expect full proposals of what will be produced. One must conceive one’s artwork from the perspective of that faceless entity of the government. And there is one thing the government does not abide: risk. The most frightening thing about government involvement in your creative project is that ‘creative’ and ‘risk’ might just mean the same thing.

A recent development in the largely funding-dependent world of physics is the Fundamental Physics Prize, established by Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner. Unlike governments, Milner has no qualms about handing out millions of dollars at a time to people of excellence to dispose of as they please, and he annually awards multiple physicists with $3 million each, plus some other negligible amounts far greater than any artist dares contemplate more than momentarily. The Fundamental Physics Prize Foundation’s website declares that the organisation is ‘dedicated to advancing our knowledge of the Universe at the deepest level.’ The prizes are awarded to ‘provide the recipients with more freedom and opportunity to pursue even greater future accomplishments.’ Significant discoveries might snap up the award, as might promising young researchers with less results under their belts. In an interesting twist, each year’s collection of winners chooses the following year’s recipients.

Milner is an entrepreneur. He takes risks. He knows that no one ever achieved anything out of the ordinary by playing safe. And it’s extremely unreasonable to expect that people with limited resources will achieve excellent things in a predetermined (and limited) timeframe. An archaeologist can’t guarantee she’s going to make the most significant discovery of the decade on her next dig. A playwright can’t determine whether or not the play will flop in advance, or there would be no bad plays. Every time we try to bring something amazing into the world, we expose ourselves and set ourselves up to fail. Every creative person knows that their work takes time, effort and persistence, and that it doesn’t pay off every time. Government asks the impossible of us, demanding to know the (positive) outcome at the outset.

Nationalbibliothek, Wien

If artists must take risks and governments must minimise risk, the funding paradigm seems fundamentally flawed. We want our governments to appreciate art, and to instil such an appreciation in the population insofar as they are able. But perhaps to get the freedom we need, we’d be better off financially supporting ourselves, or finding entrepreneurs who believe art can ‘advance our knowledge of the Universe at the deepest level.’ And just you try to sit in front of a Vermeer and say he didn’t advance just that.

Detail of The art of painting, Vermeer; Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien