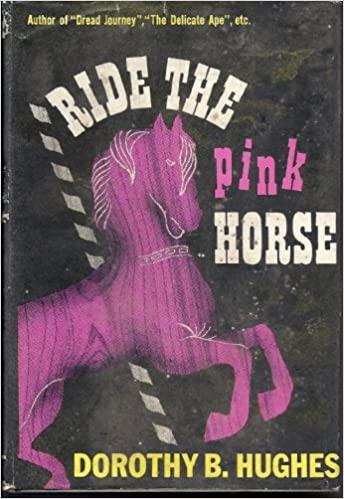

Book Review by Jane V: I fetched a deep sigh on contemplating November’s ‘hard-boiled fiction’ assignment. I didn’t look forward to reading about testosterone fueled guys gunning up freeways, slugging each other and knocking back immoderate amounts of whiskey. So I decided to find out if any female writers had attempted the genre, thinking that they would be more bearable – and found Dorothy B Hughes. Hughes wrote at least seven books in the ‘hard-boiled’ crime genre. She was an American literary critic, historian and author who, early in her career, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Competition for her poetry collection Dark Certainty.

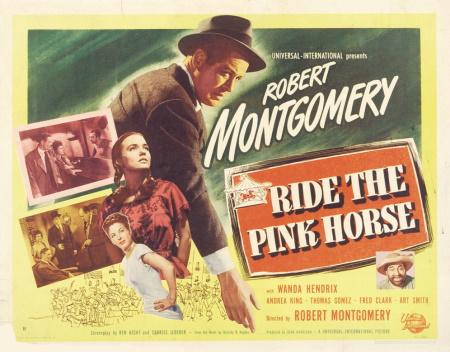

I chose Ride the Pink Horse published in 1946 and made into a film starring Robert Montgomery in 1947. In 1964 it was remade for television as The Hanged Man.

The story is set on the Mexican border of the US at fiesta time. There has been a crime, the murder of a senator’s wife, but this is in the past and took place in Chicago. The murdered woman’s husband, Senator Willis Douglass is a corrupt politician, weaselly of face and skinny of leg. He is in the habit of ‘adopting’ youths from disadvantaged backgrounds, grooming them and employing them to carry out his ‘business’. The central character, named only as ‘Sailor’, is Douglass’ so-called secretary. Sailor takes a long-distance bus to a small town on the border with Mexico. Gun concealed in his pocket he is looking for the ‘Sen’ – the senator – who owes him money and has also traveled to this insignificant ‘hick burg’ for fiesta. Sailor plans a new life of ease and luxury for himself over the border in Mexico when he gets the money. ‘He’d set up a little safe business of his own in Mexico, making book (? betting?) or peddling liquor, quick and easy money, big money. He’d get himself a silver blonde with clean eyes. Marry her.’

Inevitably included in the picture is ‘Mac’ MacIntyre, a good cop from Chicago homicide department who has been detailed to solve the murder and is trailing Sailor and the Sen to gather clues. Mac is a type – ‘close-mouthed, McIntyre. Tight-mouthed and gimlet-eyed, his eyes going through what you said into what you were thinking’.

The other force for good is the old half Indian, half Spanish man who works the merry-go-round. Named ‘Pancho’ by Sailor he is

‘fat and shapeless and dirty, but his brown face was curiously peaceful. His overalls were worn and faded, held up by dirty knotted string; his blue shirt smelled of sweat and his yellowed teeth of garlic, his hat was battered beyond shape.’

But ‘Pancho’ also has dignity. And it is this character who repeatedly comes to the rescue of Sailor, letting him sleep on the merry-go-round when Sailor is unable to find a hotel bed, even insisting on lending him his smelly old blanket against the cold of the night. Sharing his tequila bottle with him. It is ‘Pancho’ who recognises the good in Sailor.

The first third of the story sets the colourful scene. Fancy dress costumes are described in all their vibrant colours; the ethnic mix of indigenous Indians, the descendants of the Spanish conquistadores and visiting ‘gringoes’ among whom are Senator Douglass surrounded by a flotilla of the idle rich, is observed in great detail. The thronging crowds, the noise, dust, heat and sheer press of bodies surging along the streets is presented in vivid detail. Sailor has suffered a long and exhausting journey and what is worse, sweaty and dishevelled, he is unable to find a hotel room, even in the shabbiest place in town. The ‘Sen’, of course, is staying at the most luxurious hotel in the most expensive suite. Sailor roams though the crowd trying to spot the senator as night falls. This gives Hughes ample opportunity to paint lavish descriptions of the procession to a hill outside town where Zozobra, an effigy symbolising evil is to be burnt. Hughes describes this primitive custom in dramatic and lurid detail.

‘Zozobra. Made of papier mache and dirty sheets, yet a fantastic awfulness of reality about him. He was unclean. He was the personification of evil.’

‘In destroying evil, even puppet evil, these merrymakers were turned evil. He saw their faces, dark and light, rich and poor, great and small, old and young. Fire-shadowed, their eyes glittered with the appetite to destroy. He saw and he was suddenly frightened.’

This spectacle of primitivism has an unsettling effect on Sailor as do the Indians whose impassive, slant-eyed faces remind Sailor of the stone head which had instilled fear into him on a school visit to a museum. He feels himself to be the alien; loneliness overcomes him.

‘. . . standing there the unease came upon him again. The unease of an alien land, of darkness and silence, of strange tongues and stranger people, of unfamiliar smells, even the cool of the night smell unfamiliar. What sucked into his pores for that moment was panic although he could not have put a name to it. The panic of loneliness; of himself the stranger although he was himself unchanged, the creeping loss of identity. It sucked into his pores and it oozed out again, clammy in the chill of night.’

Hughes is more interested in describing the atmosphere, the sights and sounds of a town in fiesta mood, even the oppressive heat and the dramatic thunderstorm, than in pursuing the crime element of the story. She explores the differing mentalities of the three social groups in the town. At some length she illustrates the Indians’ philosophy of life. Their passive, unreadable faces are timeless, as though they know that in some distant future the land will once again return to them and they will assume their rightful place in this border wilderness. They have no sense of urgency. Their faces remind Sailor of a carved stone head he once saw on a school visit to a museum. The implacable head frightened him back then and haunts him even now. This feeling of fear returns when he looks into the unreadable faces of the Indian women sitting silent along a wall. The Spanish, on the other hand, are loud, cheerful and lackadaisical. They are represented by ‘Pancho’ the scruffy, good-hearted operator of the merry-go-round; the rich whites are arrogant, insensitive, selfish, ‘too gay, satin-and-silk-and-velvet gay, champagne gay; they were a slumming party, leaving their rich fastness momentarily to smell the unwashed part of Fiesta.’

Little by little Hughes builds up the character and background of Sailor. We learn that he came from a poor family. His father was a violent drunk and his mother an oppressed drudge. The ‘Sen’ offered him a way out of this life, educated him and inducted him into his inner circle. The drawback is that the senator is corrupt and those around him are employed to do his dirty work. ‘Mac’ too knew Sailor as a boy, a boy who was often in trouble with the law and whom he had tried on many occasions to persuade to quit stealing cars and to go straight. Mac also came from a poor neighbourhood. The contrast between the two is stark. Sailor wants to make life better for himself. Mac wants to make life better for society.

The situation surrounding the murder is sketchily described. The main preoccupation of the story is in the balance between the four main characters: Sailor, the Sen, Mac and Pancho Villa – the opposition of good and evil. All this is set against a backdrop of the temporary destruction of evil in the burning of Zozobra as part of the fiesta celebrations. And the struggle between good and evil is taking place in the soul of Sailor too as he hunts out the Sen, softens to the innocence of an Indian girl for whom he buys a soda and a ride on the merry-go-round, comes to rely on the generosity and friendship offered him by Pancho; is sickened by watching the senator squiring a fresh and innocent rich girl. But in his relentless determination to get the money and more owed him by the senator he denies himself the opportunity to help Mac prove his hunch about the identity of the murderer and so, finally, he himself is destroyed.

The last we see of Sailor is a broken man staggering away into the dark, terrifying wilderness, weeping.

I found much more in this novel than I expected to find and was pleasantly surprised that I really enjoyed reading it. There is murder, corruption, blackmail, double-crossing but there is also generosity and kindness of the human spirit, concern for others. The central figure is not all bad and the reader is invested in his struggle between self interest and concern for others. The battle between good and evil is not only within the soul of one man, it is also represented externally in the persons of two men who have influenced Sailor, one for evil, one for good. The larger scene too emphasises this struggle in the fiesta back drop where the primitive custom of burning Zozobra the effigy of evil is annually celebrated. But, remarks Hughes, everyone knows that after fiesta evil will return once again.

Much of the language of description shows Hughes’ poetic side. As a candle lit church procession winds its way up a hill towards a white cross: ‘The sky was blue black as the night, the stars were distant . . . across the band of the naked horizon a zig-zag of lightning ran through far violet clouds. And a wind came up as out of the lightning, wavering the candles.’ The hard-boiled element surfaces in the dialog – words such as ‘hick’, ‘spic’. And many more words I didn’t understand. But didn’t need to!

The viewpoint of the story is Sailor’s entirely. Throughout it is the voice of Sailor that we hear, Sailor’s thoughts, Sailor’s fears, his loneliness, his wavering emotions, his mental struggle. Although the narration is in the third person it reads as though ‘he’ is ‘I’. It is, I discovered, an atmospheric, well-constructed and literary novel. And a very good read.

The 1947 film, directed by and starring Robert Montgomery.

The 1947 film, directed by and starring Robert Montgomery.