Fishermen upon a Lee-Shore in Squally Weather (1802) J M W Turner

The exhibition encompasses art from the 18th century right up to modern times and follows the idea of Romanticism through successive art movements and individual artists. It explores exactly what it is that draws us back and how the concept finds expression in different time periods and in the hands of different artists. Nature is a strong part of this, and it is no coincidence that Romanticism grew just as the world became mechanised. In our most 'unnatural' of times it seems we reach out to the land and sky to comfort us, but also to strike us with awe.

Sedak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion (1812) John Martin

If it is awe you are after then the sight of the tiny man at the mercy of the hellish volcanic landscape is about as brutal as it gets. The majesty of nature and its sheer terrifying scale is so well illustrated in Martin's piece. Like Turner's painting, there is feeling that nature holds power far greater than any factory or machine that humans can think of, and is of a scale that we can barely comprehend.

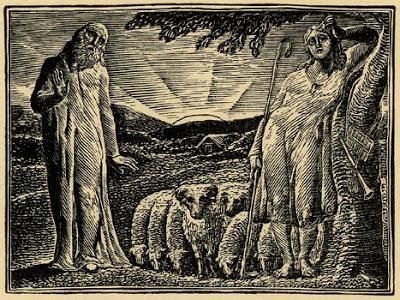

The Pastorals of Virgil William Blake

Saying that, there are some exquisite wood-engravings by William Blake on display. Tiny in size, each shows an aspect of the rural ideal of tending sheep, growing crops, working in the fields, all to illustrate Virgil's poems about Arcadia.

Romeo and Juliet (1884) Frank Dicksee

Obviously one of the main reasons I was there was to see the Victorian art and I was not disappointed. If you know anything about Southampton Art Gallery, you'll know about the Perseus Room which houses Burne-Jones' wonderful pictures of the story of Perseus, his battle with Medusa and the rescue of Andromeda. It is a room I have to be dragged out of whenever we visit. Anyway, Southampton also have other famous pieces of Victorian art in their collection, including this one of Romeo and Juliet. The Victorians took Romanticism rather more literally than their Georgian counterparts and the strong themes of love and sentiment shine through.

Afterglow in Egypt (1861) William Holman Hunt

Holman Hunt's Afterglow in Egypt is absolutely stunning in real life and so if you see the exhibition for one reason, this is a pretty good reason. The Pre-Raphaelite use of nature and fantasy in their works includes pieces like Afterglow where it could almost be seen as a recording of fact, a real place, a real person, but the level of detail and the perfection of the beautiful birds, the abundant harvest and the gorgeous young woman all suggest a dreaming for a place not like our own, a simpler way of life, a lost beauty. Those are some impressively fat exotic pigeons.

Launcelot at the Chapel of the Holy Grail (c.1890) Edward Burne-Jones

Tennyson's Arthurian poetry was entirely at odds with a period that prided itself on materialism and industrialisation. By embracing the chivalric, romantic vision of a mythical past, the Pre-Raphaelite followers continued the counter-culture well into the 20th century. Burne-Jones is quoted in the catalog that accompanies the exhibition as having said a painting was 'a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, that will never be...' and that yearning for an impossible perfection can clearly be seen in the Pre-Raphaelite's works.

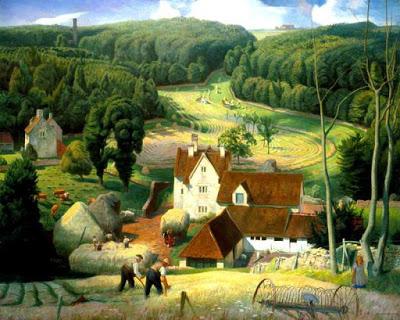

Haytime in the Cotswolds (1939) James Bateman

I was once at a gig where the people in front of us were only there to see Toyah and once she had done her stuff they got up and left, but I'm sure you aren't the sort of people to leave after the Pre-Raphaelites. In the following 20th century rooms there are some utterly delightful works including this gorgeous canvas by James Bateman. Painted as we headed into the Second World War, it shows a peaceful farm in the Cotswolds where the hay is still mowed with a scythe and a horse brings the crops home. Very soon the world would turn to Land Girls digging for victory, but in this moment the peace and quiet is not disturbed by anything more than a scythe through grass or the sound of hooves. The 20th century romantic thread struck me as one of quietness which could in no way be applied to the 18th century root with its crashing waves and volcanic landscape.

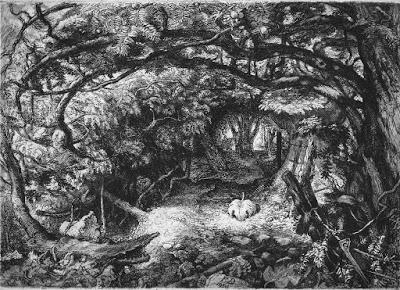

Michelham Yews III (1950) Paul Drury

The works on show go right up to 2016 but I'll finish with this one as I was struck how much it reminded me of William Blake. Paul Drury's father was the sculptor Alfred Drury, and his pastoral etchings such as this one were inspired by Samuel Palmer's rural idylls. There is something slightly threatening and fairy-tale-ish about the path through the yew trees, but again a quiet danger rather than the obvious threat of nature. The vague constriction of the trees, the hint of jaws in the log on the left all make you suspect that nature is a force to be reckoned with, whether it is struggling to control your fishing boat in a stormy sea or walking through a wood on a semi-illuminated path. Romanticism holds nature as a thing of wonder and mystery, and there is a terrible beauty that has to be acknowledged, if only for our own safety, but also for the nourishment of our souls.The Romantic Thread in British Art runs from today until 4th June 2016 and for further information see Southampton City Council pages. There is a catalog to accompany the exhibition, available from the gallery shop for £12.