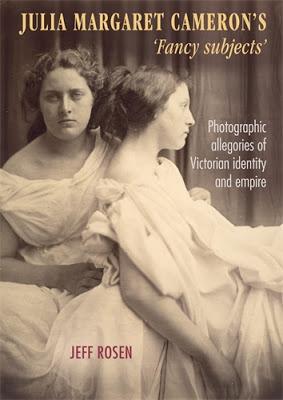

Along with her portraits of the great and the good, and her Madonna pieces, Julia Margaret Cameron created photographs which she called her 'fancy subjects', based on literature, mythology and parables. While some of the pictures moved fluidly between her categories (a recognizable person could also be a personification of something), the 'fancy pieces' gave an unwitting insight into the creator's mind, opinions and prejudices.

Poor Jo Oscar Rejlander

By the 1850s, the term 'fancy picture' referred to isolated subjects in suspension of their activity, and were often overtly religious or sentimental, as in Cameron's early collaborator Oscar Rejlander's tear-jerking Poor Jo. The pictures were traditionally genre pictures, theatrical, nostalgic or erotic, drawing on 18th century traditions of art. It was into this Cameron brought her own vision.

Madonna and Two Children (1864) Julia Margaret Cameron

The most interesting aspect of this book is how it challenges us to grasp how controversial Cameron's works were (and often still are, if the context is realized). Her many Madonna images featuring her housemaids, predominantly Mary Hillier, raise the question - is this an image of Mary or 'Mary'? Does it matter whether we think we are looking at the mother of Christ or just a maid? What is the implication of us knowing the difference? Although Cameron actively pursued (and captured) an image of Benjamin Jowett, the book discusses the tension between Jowett's religious writing and Cameron's use of religion, her tangible Christ child, her gender-bending St Johns.

Déjatch Alamayou and Basha Félika (Prince Alamayou and Captain Speedy) (1868) Julia Margaret Cameron

The book examines the Victorian identity and its relationship with Empire. I don't think it is a coincidence that most people discussing Cameron's work tend to tread carefully around the subject as it is not one that reflects well on anyone, nineteenth century opinions being so different to what we consider acceptable today. The chapters on Race, Tennyson's ideas of Nationalism and Marianne North in Ceylon tackle the questions of accepted prejudice and revealing allegiances that don't make pleasant reading, but all discussions of England's Empire are necessary in order to understand the context in which the works came into existence. For example, this chap...

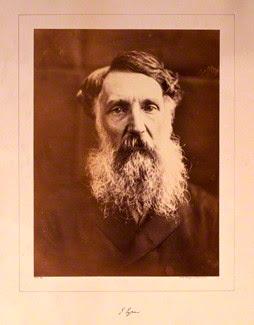

Edward John Eyre (1867) Julia Margaret Cameron

At first glance he blends into the mass of beardy Victorian chaps, but Edward Eyre was the erstwhile Governor of Jamaica, not afraid to quell the natives with questionable methods, but when he returned to England after the Jamaican Rebellion Cameron pursued him for her gallery of heroes. In the 1868 exhibition, he hung beside Carlyle and Trollop. Her friends, such as Tennyson, all subscribed to his defense as the hero of the Colonies and protector of English interests in the Empire. What we are forced to consider is whether Cameron was naive enough to not look into the background of her friend's friends, the celebrity of the moment, or whether she also believed he was a good man doing good English work. In the case of Captain Speedy and the orphaned prince of Abyssinia, world events landed on Cameron's doorstep with the arrival of Speedy and his charge on the Wight. I'm not sure if Speedy's acquaintance with Cameron was gained because he was the brother-in-law of Mary Ryan (Speedy was married to Henry Stedman Cotton's sister) or through her force of personality, but Cameron took several images of the little Prince, Captain Speedy and their Abyssinian companion. Whilst most of the images are typical Victorian Empire shots filled with native knick-knacks and trophies, Spear or Spare slides over into truly offensive role-play, as Speedy pins down the man who in previous shots had sat beside them as a friend.

And Enid Sang (1874) Julia Margaret Cameron

I especially enjoyed the chapter on Tennyson and nationalism, the use of Tennyson's poetry (Cameron's photographic re-imagining of it) to explore notions of nationhood and national identity. The dream of an alternative, medieval utopia as given voice in Idylls of the King, found a physical presence in Cameron's 1874 large-scale photographic edition. There is much discussion about the purposefully assertive, isolated female voice of the poem reflected in the single figure images, as above, and it is in these works I find most harmony between Tennyson's words and Cameron's pictures.

Young Woman, Ceylon (1875-9) Julia Margaret Cameron

When she returned to Ceylon in the 1870s, Cameron's subjects not only reflected her attitude to England's Empire but also featured the people at the sharp end of the Colony. The book contrasts images such as the above with similar images of Mary Hillier in her Madonna garb and complex discourse ensues. Often the last couple of years of Cameron's life and her sparse existent images are taken as separate from the Freshwater time but the question is whether it is right to segregate the images or too simplistic to read them together. The image of a Ceylonese woman becomes loaded when it is considered that the creator is one of the ruling class, but I find it interesting to consider the young unnamed girl (isn't it interesting that she has no name?) and her position in comparison to the Freshwater servants. The inclusion of the 'western' Marianne North into the 'primitive' surroundings of the plantation brings further layers of meaning and confusion. In the end Cameron's attitude to the natives of both islands draws out her attitude to the Empire, England and those who rule it. It's not comfortable or easy reading but it raises many thought-provoking questions which places Cameron in context, for better or worse.

Marianne North (1877) Julia Margaret Cameron

To buy Julia Margaret Cameron's 'fancy subjects': Photographic allegories of Victorian identity and empire visit Amazon UK here or USA here (out in July) or order from a bookshop near you.