Contributor: John Keegan

Written by Bob Baker and Dave Martin

Directed by Mike Hayes

It’s easy to forget, in the days of the War on Terror and economic frailty, that there was a time when the world was gripped by fear of mutually assured destruction via nuclear war. Nuclear weapons haven’t left the general consciousness entirely, as tensions with Iran and North Korea and worries over “suitcase bombs” indicate, but the sense of impending nuclear doom in 2013 is nothing compared to the heyday of the Cold War.

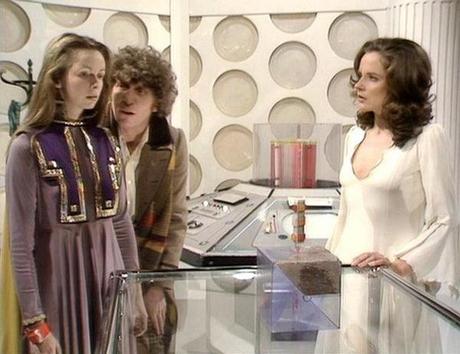

Bringing the “Key to Time” saga to a resolution, and also marking the final appearance of Romana I (sadly, as Mary Tamm is drop dead gorgeous), this is perhaps the most serious of the stories set during the epic fetch quest. It also marks the first appearance of the Black Guardian’s servants, which is a nice touch. It weakens some of the previous stories in retrospect, since one immediately wonders why the Doctor wouldn’t have run into the Shadow on other occasions, but one can accept the simple explanation that the Shadow figured it would be easier to let the Doctor search for the other five pieces, once the sixth and final piece was secured. (It’s the most obvious flaw in the “competitive fetch quest” plot device, especially when all the pieces need to be collected to get the job done!)

Touching back on the Cold War metaphor, the Marshall presents a compelling adversary of sorts. One of the fears on the American side of the Cold War was the possibility of “sleeper agents”, even regular citizens that had been “programmed” to act against their will for the purposes of the evil Soviet empire. The Marshall has an inherent bloodlust and lack of perspective, but he’s also under the control of the Black Guardian. Where does his will end, and the mind control begin?

It speaks to the larger metaphor of the White and Black Guardians. Their origins are an unnecessary detail; they are clearly an embodiment, for the purposes of the Whovian mythos, of good and evil. But as with all good pulpy science fiction epics, it’s all a matter of perspective. The White Guardian may be more persuasive, and give the Doctor more of an impression that it’s his choice, but the Doctor is still serving an interest beyond his full understanding. He is reduced, to a certain degree, to a function. The Black Guardian simply strips away the illusion of free will in the endeavor.

This scenario raises the question: how often do we act in the interests of others, and how often do we do so with full awareness and agency? Coercion is rarely so obvious as it is with the evil Black Guardian and his control mechanism, neatly placed on the neck. What pressures are brought to bear that influence into decisions we might normally avoid? And how often does this lead to results more destructive than we would otherwise desire? (Hardly an intellectual exercise in today’s society, is it?) Launching the story with the cheesy, propaganda-laced soap opera is all the more fitting as one considers the thematic qualities of the production.

At any rate, the Doctor’s choice to re-disperse the fragments of the Key is in keeping with that ever-classic solution to similar dilemmas: when presented with two questionable choices, go with neither. It always seems so brave and bold a choice, because humans have a tendency (programmed, perhaps?) to think of matters in binary: everything seems to come down to two seemingly mutually exclusive choices. The fact that the portended doom never comes, when the Key is not delivered to the White Guardian, is a fitting and telling end.

Douglas Adams was stepping in as script editor by this point, and it’s fairly apparent. As grim and dark as this serial is, there are moments of odd and dissonant absurd humor. The Doctor’s banter with Romana (and just about everyone else) is just this side of sheer madness, and Drax is so odd that it’s not entirely clear if the Doctor really remembers those good old days on Gallifrey or just figures it’s easier and safer to play along. (Though, I must admit, the explanation Drax gives for his accent and affectations is brilliant.)

The main weakness is, oddly enough, the Shadow himself. Thematically, he plays a necessary role. In execution, he is utterly ridiculous. I can overlook the costuming, more or less, but the maniacal laughter is way over the top. Given how well the Marshall was portrayed, the Shadow would have been much better with more nuance to the performance. It’s also far too long for its own good. This could, and should, have been a four episode serial. Instead, it is the last six-episode serial, and one might imagine why that is.

“The Armageddon Factor” is, in the end, a serial filled with great ideas, perhaps not executed as well as they could have been. It relies a great deal on the psychological context of its time, and it also exposes how poorly constructed the overarching “Key to Time” quest was. In the hands of a more skilled long-form storyteller, this could have been a season of wonders. Instead, it was an uneven exercise, and one that exposed the weaknesses of the writing during this period of the classic franchise.

Writing: 1/2

Acting: 2/2

Direction: 2/2

Style: 2/4

Final Score: 7/10