Oil drill outside of Colby, Kansas. (Credit: Flickr @ Lyndi & Jason http://www.flickr.com/photos/citnaj/)

Oil drill outside of Colby, Kansas. (Credit: Flickr @ Lyndi & Jason http://www.flickr.com/photos/citnaj/)Researchers from the University of Maryland and a leading university in Spain demonstrate in a new study which sectors could put the entire U.S. economy at risk when global oil production peaks. This multi-disciplinary team believes that so-called “peak oil” will happen really soon, and recommends immediate action by government, private and commercial sectors to reduce the vulnerability of these sectors.

Peak oil, according to M. King Hubbert’s Hubbert peak theory, is the point in time when the maximum rate of petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production is expected to enter terminal decline. Global production of oil fell from a high point in 2005 at 74 mb/d, but has since rebounded setting new records in both 2011 and 2012. There is active debate as to when global peak oil will occur, how to measure peak oil, and whether peak oil production will be supply or demand driven.

According to the International Energy Agency’s analysis, “there are ample physical oil and liquid fuel resources for the foreseeable future,” and “a combination of sustained high prices and energy policies aimed at greater end-use efficiency and diversification in energy supplies might actually mean that peak oil demand occurs in the future before the resource base is anything like exhausted.”

While critics of peak oil studies declare that we are not running out of oil yet, and that the world has more than enough oil to maintain current national and global standards, these researchers say peak oil is imminent, if not already here—and is a real threat to national and global economies.

Their work, “Economic Vulnerability to Peak Oil,” appears in Global Environmental Change (see footnote). The paper is co-authored by Christina Prell, UMD’s Department of Sociology; Kuishuang Feng and Klaus Hubacek, UMD’s Department of Geographical Sciences, and Christian Kerschner, Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

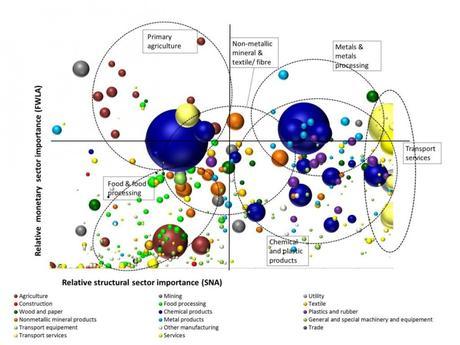

The figure above shows sectors’ importance and vulnerability to Peak Oil. The bubbles represent sectors. The size of the bubbles visualizes the vulnerability of a particular sector to Peak Oil according to the expected price changes; the larger the size of the bubble, the more vulnerable the sector is considered to be. The X axis shows a sector’s importance according to its contribution to GDP and on the Y axis according to its structural role. Hence, the larger bubbles in the top right corner represent highly vulnerable and highly important sectors. In the case of Peak Oil induced supply disruptions, these sectors could cause severe imbalances for the entire U.S. economy. (Credit: See citation at the end of this article)

Until now, little has been known about how peak oil may impact economies. In their paper, the research team constructs a vulnerability map of the U.S. economy, combining two approaches for analyzing economic systems. Their approach reveals the relative importance of individual economic sectors, and how vulnerable these are to oil price shocks. This dual-analysis helps identify which sectors could put the entire U.S. economy at risk from Peak Oil. For the United States, such sectors would include iron mills, chemical and plastic products manufacturing, fertilizer production and air transport.

“Our findings provide early warnings to these and related industries about potential trouble in their supply chain,” UMD Professor Hubacek said. “Our aim is to inform and engage government, public and private industry leaders, and to provide a tool for effective peak oil policy action planning.”

Although the team’s analysis is embedded in a peak oil narrative, it can be used more broadly to develop a climate roadmap for a low carbon economy.

“In this paper, we analyze the vulnerability of the U.S. economy, which is the biggest consumer of oil and oil-based products in the world, and thus provides a good example of an economic system with high resource dependence. However, the notable advantage of our approach is that it does not depend on the peak-oil-vulnerability narrative but is equally useful in a climate change context, for designing policies to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. In that case, one could easily include other fossil fuels such as coal in the model and results could help policy makers to identify which sectors can be controlled and/or managed for a maximum, low-carbon effect, without destabilizing the economy,” Professor Hubacek said.

One of the main ways a peak oil vulnerable industry can become less so, the authors say, is for that sector to reduce the structural and financial importance of oil. For example, Hubacek and colleagues note that one approach to reducing the importance of oil to agriculture could be to curbing the strong dependence on artificial fertilizers by promoting organic farming techniques and/or reducing the overall distance traveled by people and goods by fostering local, decentralized food economies.

Christian Kerschner, Christina Prell, Kuishuang Feng, Klaus Hubacek (2013). Economic vulnerability to Peak Oil Global Environmental Change DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.08.015