The following is just part of an excellent and thought-provoking article by David M. Drucker in Vanity Fair:

The following is just part of an excellent and thought-provoking article by David M. Drucker in Vanity Fair:The transition from the Party of Lincoln to the Party of Reagan, and now to the Party of Trump, did not happen overnight. In 1950s America, the one that the enthusiastic Trump voter might have in mind when the president pledges to “Make America Great Again,” the progressives were Republicans. There were few Republicans in the South back then—whether voters or politicians. But those that existed were generally at the forefront of advocating for civil rights, in the tradition of the party that formed in part to end chattel slavery of African-Americans and the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, who prosecuted the Civil War that extinguished it. The Democratic Party, the party of the Confederacy and the Old South, still represented racism and oppression, and to the extent that African-Americans were able to vote, they tended to vote Republican.

That began to change in 1964, when U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater won the Republican presidential nomination. The libertarian from Arizona opposed federal civil-rights legislation on federalism grounds, a position rejected by liberal whites and, naturally, African-Americans. President Lyndon Johnson, who was accelerating the Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights and racial tolerance, crushed Goldwater in the general election, fueling the movement of white Southern Democrats toward the G.O.P.

To a degree, it was the organic consequence of the two parties’ shifting attitudes toward whether the federal government should force states to honor and uphold the civil rights of African-Americans. But it also was the result of a deliberate strategic choice made by the Republicans. As the debate over civil rights roiled the U.S. and the fabric of American society was stretched thin by the loosening of traditional social norms, the Republicans spied a path to a governing majority, and an end to a losing streak that by the mid 1960s included 7 of the previous 9 presidential elections and 14 out of 16 elections to determine control of Congress. Millions of voters were scared that the country was unraveling; they were uncomfortable by what they perceived as a disregard for authority, disrespect of country, and devaluing of religion and the family. A good number of them were in the South.

Republicans also courted them, sometimes with forthright policy appeals to restore conservative governance and traditional American values, sometimes with coded language—as Lee Atwater infamously explained—that preyed upon their unease with racial equality. . . .

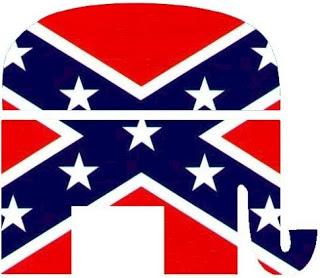

The current debate over Confederate symbols cuts to the central, existential question hanging over the G.O.P. The Republican Party today is an amalgam of upscale white suburbanites who are moderate on social issues but conservative on fiscal and national-security issues, and exurban and rural populist working-class whites, who are quasi-liberal on economic matters and foreign policy, but conservative on politically charged social issues.

But the key demographic in this coalition is “white.”

The Republicans becoming the guardians of the Confederacy is a function of the G.O.P. becoming so predominantly white, and yes, the predominant party in the South. The Republican project to take over the South was completed in 2010, when the red wave that swept Republicans into power in Congress and state capitals across the country ejected the last remnants of white Democratic authority. So by the time Trump responded to Charlottesville with vows to protect “our culture” and “our history,” and protect Confederate monuments from being relegated to some museum’s dusty storeroom, there were few sympathetic voters left in the Democratic Party to cheer him on. But there were plenty of Republicans.

“The Republican Party didn’t just capture the South; the South captured the Republican Party,” said Matt K. Lewis, a conservative writer for the Daily Beast, and CNN commentator. . . .

The modern-day manifestation of that is a rejection of anything deemed “politically correct,” a boiling sentiment that helped propel Trump to the Republican nomination last year, and then, the presidency. You could say that defending the Confederate statues, symbols, and historical figures, in 2017, is peak political incorrectness. . . .

The Republican Party is in the midst of its own civil war, one likely to play out in G.O.P. primary contests for the House and Senate throughout the 2018 midterm cycle. The outcome could determine whether Reagan-era conservatism, or Trump-styled white identity politics, comes to define the party brand. Steve Bannon, the nationalist firebrand behind Breitbart News and Trump’s former chief strategist in the White House, is raising resources and recruiting primary candidates to challenge G.O.P. incumbents on the 2018 ballot, with the goal of electing more like-minded Republicans: economic populists, immigration restrictionists, foreign policy non-interventionists. Joined by a cadre of co-conspirators on the right, his goal is to expel, among others, the Republicans who have been at the forefront of courting nonwhites to join a more inclusive G.O.P. centered around free-market economics, and comprehensive immigration-reform legislation. Republicans just like this were on the party’s primary ballot for president in 2016—and were soundly rejected in favor of Trump. Will it happen again?