I originally published this article on AHTribune.com.

I originally published this article on AHTribune.com.Repression, Uprisings, and Rebellion

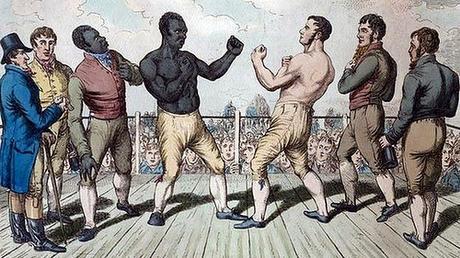

Part 1: Slavery

This series examining the history of black people in the United States isn’t one in which the usual writings focusing on slavery, the civil rights movement, and the present state of black America. Rather, it will put a lens on subject matter that is often unknown and rarely talked about, from how the North benefitted from slavery to the creation of the ghetto to alleged government involvement with the transportation of drugs into the black community. While the story of black people in the US is viewed generally as one of struggle, however it is also one of rebellions and uprisings against unjust conditions. In many ways, it is a story of resistance and hope against seemingly indomitable odds.SlaverySlavery, generally viewed as a purely racist institution, was at its core about economics. The need for free labor was quite great in colonial America and “when it became clear that freemen would not come and work for hire, a demand developed for servile labor.” [1] This labor first came in the form of indentured servants and English criminals who were sent to the colonies and used for labor as part of their punishment. However, Africans were eventually settled upon as “the planters learned at length that the negroes could be employed to very good advantage in the plantation system; and after about 1680 the import of slaves grew steadily larger.” [2]Slavery grew due to economic considerations as “wherever the immediate profits from slave labor were found to be large, the number of slaves tended to increase, not only through the birth of children, but by importations” [3] and due to the large amounts of capital invested in the slave system, it could maintain itself in times of extreme economic hardship, even going so far as to continue while running at a slight loss. Many times, the price of Africans was “so low that, when crops and prices were good, the labor of those imported repaid their original cost in a few years.” [4]Yet, while Southerners were making money from the slave trade, the North was also gaining wealth from slaves, but in a different manner.During the 1830s, slave owners in the South wanted to import capital as to purchase more slaves and they came up with a new idea: “[mortgage] slaves; and then [turn] the mortgages into bonds that could be marketed all over the world.” [5] To this end, they organized new banks, drew up lists of slaves to be used as collateral, and used those banks to sell bonds to investors from as far away as London, Amsterdam, and Paris. Planters, via their mortgage payments, paid the principle and interest on these bond payments, effectively ‘securitizing’ black bodies. Most interestingly, a rather well-known financial company gained its start due to this:

Older slave states such as Maryland and Virginia sold slaves to the new cotton states, at securitization-inflated prices, resulting in slave asset bubble. Cotton factor firms like the now-defunct Lehman Brothers — founded in Alabama — became wildly successful. Lehman moved to Wall Street, and for all these firms, every transaction in slave earned money flowing in and out of the U.S. earned Wall Street firms a fee. [6]Yet money wasn’t just made solely off of slaves, the North also helped to fund slavery itself. Nicholas Biddle, head of the United States Bank of Philadelphia, “funded banks in Mississippi to promote the expansion of plantation lands” as he “recognized that slave-grown cotton was the only thing made in the U.S. that had the capacity to bring gold and silver into the vaults of the nation's banks.” [7] Thus, while in the popular imagination slavery was a Southern institution, the North had just as much blood on its hands.The effect of slavery is long-reaching as it has even influenced management techniques that are currently used. Southern plantation owners utilized extremely meticulous methods of measuring slave productivity and tracking their profits. “Several of the slave owners’ practices, such as incentivizing workers (in this case, to get them to pick more cotton) and depreciating their worth through the years, are widely used in business management today.” [8]Slave owners were able to keep such records due to their having total control over slaves and thus they were able to try a number of different techniques on their slaves and that, coupled with the extreme accounting methods, resulted in slave owners being able to manipulate their slaves (such as using cash rewards) to see just how much cotton they could pick over a certain period of time and then turning that into the base amount from then on. “Similar incentive plans reappeared in early twentieth-century factories, with managers dangling the promise of cash rewards if their workers reached certain production levels.” [9]The Civil War itself, was somewhat based in economics. While there was an abolitionist movement in the North and in no way, shape, or form can that be downplayed or ignored, it should be noted that the abolitionists and their radical Republican allies “comprised no more than fifteen percent of the Northern population.” [10] The Republican Party as a whole was concerned with economics. With regards to Northern economics, “the most important development was the reorientation of trade from its north-south channel along the Mississippi to an east-west axis that included the Great Lakes and the Erie Canal. Shipping along the Mississippi continued to grow” [11] and east-west commerce, especially by railroad post-1855, began to be far greater than commerce on the north-south axis. Thus, the South was becoming economically less important. The Republicans responded to this westward shift by combining an anti-slavery political approach with a pro-western economic approach. The anti-slavery goals of the Republicans were limited as the most they agreed to was an opposition to the westward expansion of slavery, yet this coincided with the new economic realities as not having slavery in the west opened up the lands for white settlers.The economic conditions in the South were also changing as many planters who needed new soil to curb their growing concerns of soil exhaustion found themselves out of luck due to increased Northern opposition to the expansion of slavery. However, there was a split between those who were concerned about new soil and thus the expansion of slavery and those who weren’t. The northern counties of states like South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi weren’t too concerned about this as they were all “part of the Deep South more closely connected with the states to the north by an expanding overland trade” and “raised the most grain, and fostered a culture of small milling centers and artisan production.” [12] The ones who were most concerned about new soil came from those in the southern counties, where primarily cotton was grown. The people there were convinced that without the expansion of slavery westward, the entire system was at risk of destruction.At the end of the day, however, the southern states seceded because they feared that Lincoln and the Republicans would do away with slavery, irrevocably changing the South forever.While chattel slavery was abolished, it took two different forms, one was economic in the form of sharecropping [13] and the other based on the prison system, in the form of convict leasing which lasted until World War Two. [14]Endnotes1: Ulrich B. Phillips, “The Economic Cost of Slaveholding in the Cotton Belt,” Political Science Quarterly 20:2 (June 1905), pg 258

2: Ibid

3: Ibid

4: Ulrich, pg 260

5: Edward E. Baptist, Louis Hyman, “American Finance Grew On The Backs Of Slaves,” Chicago Sun-Times, March 6, 2014

6: Ibid

7: Sven Beckert, Seth Rockman, “How Slavery Led To Modern Capitalism: Echos,” Bloomberg View, January 24, 2012

8: Katie Johnson, “The Messy Link Between Slave Owners and Modern Management,” Forbes, January 16, 2013

9: Ibid

10: Marc Egnal, “The Economic Origins of the Civil War,” Organization of American Historians Magazine of History, 2011, pg 31

11: Egnal, pg 30

12: Egnal, pg 31

13: Devon Douglas-Bowers, Debt Slavery: The Forgotten History of Sharecropping, The Hampton Institute, November 7, 2013

14: Devon Douglas-Bowers, Slavery By Another Name: The Convict Lease System, The Hampton Institute, October 30, 2013