San Antonio-based artist Mel Casas died on November 30, 2014 after a two-year battle with cancer. The Smithsonian American Art Museum is proud to own paintings by artist, including Humanscape 62, which was featured in our exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art. In this blog post, Curator for Latino Art E. Carmen Ramos reflects on the importance of Casas' art.

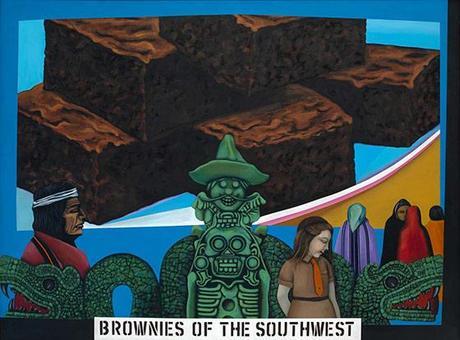

Mel Casas' Humanscape 62

I never had the good fortune of meeting Mel Casas in person. I did read about his art and spent a fair amount of time thinking about his well-known Humanscape 62. Some might wonder: what makes this painting so iconic? I believe Humanscape 62 crystallized many recurring concerns in Casas' art and early Chicano art of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

At the time he created this painting, Casas was deeply immersed in his Humanscape series. Casas started out as an abstract expressionist and in the mid-1960s returned to figurative imagery. This shift coincided with his interest in the psychology and popular media culture, especially film. The large central image in each Humanscape painting—which Casas numbered consecutively—in fact evokes a TV or movie screen populated with everyday life imagery. Initially, the series explored how the media shapes our standards of beauty and sexual desires. The prevalence of the white female figure, or what the Casas called the "Barbie Doll Ideal," indicates how he was already honing in on a race as a dominant element in American popular culture.

By the late 1960s, Casas turned his attention to the Chicano civil rights movement and the tumultuous political tenor of the times. Chicanos were active on many fronts, including protesting against racial stereotypes in the media. The National Mexican-American Anti-Defamation Committee led a campaign to eradicate the Frito Bandito, the sombrero-totting stereotypic mascot for Frito-Lay corn chips. Casas created Humanscape 62 amidst this debate to both document the Frito Bandito's existence and embody the public outrage around it. Ultimately, community efforts were successful. In 1971, Frito-Lay retired the Frito Bandito.

The power of this painting rests on how it boldly challenged authority. Casas defused the Frito Bandito, seen in green on the lower register, by surrounding it with other references that share a connection to brownness, a term that increasingly signified Chicanos and their indigenous ancestry. Casas conjured mundane references, like a junior Girl Scout, or Brownie, along with meaningful quotes of ancient sculptures of Aztec deities like Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. The huge brownies that command the top center of the painting are at once banal and historical. They refer to product-packaging for the popular cake-like treat, as much as chocolate, brownies' main ingredient, whose origin is Mesoamerican. By including the subtitle "Brownies of the Southwest" directly on the painting, Casas satirically invited viewers to ponder what and for whom these brown people and things mean.

I recently re-read Casas' Archives of American Art oral history and was struck by how often he categorized his interests under the banner "Americana." He didn't outright define the term, but for him it seemed to mean all of the cultural experiences that take place in the United States, rather than what traditionally passes as American. Looking at Casas' art, we witness an artist who prodded our awareness of multiple American realities. Perhaps this is why Casas called himself a "cultural adjuster." I treasure Casas' perspective, and others of his generation, who questioned what counts as American culture during a turning point in our national history.

If you missed seeing Casas's Humanscape 62 while on view in Our America in Washington D.C. or Miami, your can see the painting and the exhibition at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento through January 11, 2015, or at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City starting on February 6, 2015.